As China doubles down on its zero-COVID policy, Shanghai struggles through a sixth week of lockdown, and Beijing expands mass testing and targeted closures, many smaller Chinese cities and towns have endured much longer periods of closure, quarantine, and isolation. Border towns have suffered the most, with some residents confined to their homes and unable to work for months on end, economic activity and cross-border trade at a standstill, and daily life defined by constant PCR testing and shortages of food and supplies. In contrast to the flood of coverage and viral audio and video social media content from Shanghai, Xi’an, and other big cities during their lockdowns, information about pandemic conditions in these border regions is relatively scarce.

For this feature on “long lockdowns,” CDT editors have selected and partially translated a number of personal stories from several border cities. Ruili, on Yunnan’s border with Myanmar, has weathered nine separate lockdowns, totaling over 160 days, and an estimated outflow of 200,000 residents. On the border with Vietnam, the city of Dongxing in Guangxi Province has been closed for two and a half months, and as many as 100,000 of its residents have fled. Much further north, along the border with Russia, the small city of Suifenhe in Heilongjiang Province has been closed for over 90 days, with cross-border trade and economic activity reduced to a trickle. In Jilin Province, which shares a border with both Russia and North Korea, nearly nine million residents of the provincial capital of Changchun have been living under various forms of lockdown for two months. Changchun’s university students have been particularly hard-hit, as they are confined to their dormitories and subject to increasingly intrusive and baffling regulations by school administrators.

CDT editors have translated portions of a recent long-form article that first appeared in Yitiao (一条) under the title, “With the Longest Lockdown at 160 Days, These Are the Cities That Have Almost Been Forgotten.” Through personal stories, the article explores the effects of long lockdowns on residents, students, medical workers, and businesses in three of the above border cities: Ruili, Suifenhe, and Dongxing. All names that appear in the original article and the translation are pseudonyms:

Ruili, Yunnan Province: “All this seems like something out of a Gabriel García Márquez novel.”

In late July of 2021, in the brief interval between Ruili’s fourth and fifth lockdowns, Li Shang queued for five hours at city hall to apply for a permit to leave Ruili. As soon as he had the permit in hand, he raced back back home to grab his mobile phone, wallet, ID, and a few items of personal clothing, and then he drove away from Ruili without a backwards glance.

Li Shang has lived in this border town for eight years, but his departure took only 20 minutes. “You’re required to leave within 24 hours of getting the permit; otherwise, it becomes invalid. I have a sentimental attachment to this place, but at that time, all I could think about was fleeing.”

[…] Now 40 years old, Li Shang came to Ruili in 2014, rented a building, and transformed it into a youth hostel. He eventually took out a mortgage to buy a home in Ruili, the place he had come to consider “a second home,” thus putting an end to a decade of wandering.

Ruili is surrounded on three sides by Myanmar, with which it shares a border stretching 169.8 kilometers (over 105 miles). Despite the bustling import and export trade, the pace of life is leisurely. In Li Shang’s view, it is an inclusive place, full of opportunities. In addition to the local Dai and Jingpo [or Jinghpaw] people, there are transplants from various regions of China and immigrants from Myanmar, Thailand, India, and Pakistan, who bring with them their own diverse cultures and cuisines. Before Ruili’s closure, the occupancy rate of Li Shang’s youth hostel never fell below 60%, and he was planning to open another branch over the border in Myanmar.

After the city’s closure on March 31, 2021, Li Shang was unable to return to his home in the lockdown area, so he had to stay in the hostel. Between his stored food supplies and courier deliveries of fresh vegetables, he was barely able to scrape by. Although he heard a constant barrage of news about government-distributed food aid packages, Li Shang only received one delivery of government aid: a portion of herbal tea. Prices have risen considerably. A pound of red chili peppers that used to sell for 8 yuan per pound now costs nearly 40 yuan [$5.90 U.S. dollars].

What worries him even more is his business. No tourists can enter Ruili, so Li Shang’s hostel is closed, and all of its Burmese workers have left. For periods of as long as four months, he was alone in the deserted hostel, and all he could do was take nucleic acid tests and slowly lose hope.

Nearly all of Li Shang’s friends have chosen to leave Ruili. The friends who used to call each other up for an impromptu midnight snack at a food stall have now gone their separate ways in search of a living.

Ruili has been under lockdown off and on for a year now. The lockdowns have ranged from whole-city closures under strict pandemic controls to quarantine-at-home and stay-at-home orders. Since the outbreak of the pandemic three years ago, the citizens of Ruili have experienced nine city closures totalling over 160 days, and at least 130 rounds of nucleic acid testing.

[…] According to official city data, Ruili’s most recent citywide nucleic acid test on April 18, 2022, was administered to approximately 190,000 residents, whereas a nucleic acid test conducted a year ago on April 13, 2021, involved approximately 380,000 residents. This suggests that at least 200,000 people left Ruili during that year.

Jade merchant Liu Shanshan remembers having to queue for over 40 minutes to take a nucleic acid test in the early days of the pandemic. A few days ago when she went downstairs to take a test, there was no queue at all. In the building where she lives, there used to be six households on her floor, but over the past year, all of them have moved away. Now hers is the only family left, the only apartment with lights on at night.

[…] Some people have moved to Guangdong to carry on their jade-selling business, while others have returned to their hometowns. Some have found new careers as greengrocers, liquor merchants, or delivery riders. Others have relocated to nearby cities to allow their children to continue school. For over a year, most of Ruili’s primary and secondary schools have been closed. Except for third-year high schoolers [preparing for college exams], few of Ruili’s students have been able to resume in-person classes. Every day, children stay home and take online classes, some of which have an astonishing teacher-to-student ratio of 1:800.

[…] In Ruili, there are many residents who can’t sleep well at night. Liu Shanshan suffers from insomnia, worries about debts, and wrestles with the decision of whether or not to leave.

[…] “During those nine lockdowns, I was all alone at home. The longest one lasted for 28 days. There was a person across from my building who screamed and vented all day long,” [said Liu Shanshan].

[…] Li Shang now rents a house in another city in Yunnan and has switched to the business of selling tea. The money he earns not only has to cover his daily living expenses, but also the mortgage payments on his house in Ruili, which remains inaccessible. “All this seems like something out of a Gabriel García Márquez novel,” he says. Now in middle age, Li Shang finds himself adrift once again.

Dongxing, Guangxi Province: “Ordinary people seem to be caught in an impossible dilemma, a no-win situation.”

Fifty days after the city of Dongxing in Guangxi Province went into lockdown, a widely-shared Wechat video showed a middle-aged man from Dongxing cradling his head and sobbing, driven to the verge of collapse by 50 consecutive rounds of nucleic acid testing.

Every local who watches the video experiences a surge of emotions, like a floodgate opening, because they understand that sense of utter despair. This is Dongxing’s longest lockdown since the pandemic first erupted in early 2020, and no one knows when it will end. All they can do is wait.

[…] Gu Yue, originally from Sichuan, in her sixth year in Dongxing. She runs a small shop at the city’s port, selling Vietnamese specialties such as durian cakes, salted cashews, coffee, and tourist souvenirs. She has two children to support.

The port of Dongxing isn’t very large, and is separated from Vietnam only by the Beilun River [known in Vietnam as the Ka Long River or Bắc Luân River]. The river is spanned by a 111-meter-long bridge connecting the two countries. In the past, when Gu Yue stood at the door of her shop, she could see Vietnamese people playing basketball on the opposite shore of the river.

Dongxing is a county-level city under the administrative jurisdiction of the larger city of Fangchenggang. Past data reveals that Dongxing was home to approximately 200,000 residents, of whom 150,000 were migrants from other provinces. Most people earned their living from tourism, Sino-Vietnamese trade, or related industries that were the mainstays of the city’s economy.

Gu Yue recalls how Dongxing’s port looked in late 2019, when “this whole place was just dazzling.” What was once a bustling sea of people, busily stocking up on items for the new year, is now a scene of desolation.

[…] Since the imposition of “grid management,” this small city has been divided into “infectious zones” and “non-infectious zones.” If a building has even a single positive case of COVID-19, all residents of that building are dragged off to a quarantine facility. Dongxing’s long-empty streets and shuttered shops with their rustic signs seem to reflect the torpor of this once-vibrant port city.

[…] Figures from the most recent citywide nucleic acid screening test show that Dongxing’s population has dropped to under 70,000, which suggests an outflow of over 100,000 migrants from other provinces. Some residents of Dongxing, however, cannot leave.

Xiao Xiao migrated from Hunan to Dongxing more than two decades ago. Her household registration is now based in Dongxing, which she views as her “second home.” Vigorous and enthusiastic, she worked for 18 years in the media advertising industry.

When the pandemic began, she was among the first to sign up as a volunteer. “At first, everyone was motivated and enthusiastic, hoping to help bring the pandemic to an end.” But as the interminable lockdown stretched on, she could feel her own enthusiasm slowly ebbing away.

Volunteers do the most arduous and tiring work, enduring almost daily nucleic acid testing and daytime temperatures that during the spring, can approach 30°C (86°F), while wearing airtight white hazmat suits. “It’s like you’re wrapped up so tightly you can barely move.”

On the night the city went into lockdown, Xiao Xiao happened to be in the suburbs and couldn’t get back to her home in the city, so she and her husband found themselves isolated in two separate locations. Even under lockdown in the suburbs, her life is a bit freer than if she were in the city. Standing on her rooftop, she can see the fields and mountains in the distance, which she says “provides a bit of comfort in the midst of the pandemic.”

A natural optimist, Xiao Xiao does her best to keep her spirits up, even at the saddest of times, but there are pressing matters to contend with. Her father, currently locked down in a separate location, underwent a surgery for lung cancer that left him with only one lung. He now requires daily doses of targeted molecular therapeutics to keep him alive. But what will happen if his medicine runs out during lockdown? The entire family feels helpless.

In Dongxing, ordinary people seem to be caught in an impossible dilemma, a no-win situation. In the meantime, as they wait for the lockdown to lift, everyone is suffering.

Suifenhe, Heilongjiang Province: “This long-suffering city has been forgotten”

The city of Suifenhe has experienced intermittent closures since January 25 of this year, with express delivery, pharmacies, and hospital outpatient clinics at a standstill. For resident Xiao Fang, a freelance designer born in 2002, the greatest torment isn’t the inconvenience of daily life, but the loss of sleep.

With a complex history of psychiatric issues, and recurrent episodes of anxiety and insomnia, she faces the risk of running out of the tranquilizers and sleeping pills she needs. “I’m in a difficult predicament, but the general consensus seems to be that mine isn’t a major medical emergency, so I haven’t been able to get prescriptions.”

She began taking her medicine sparingly, reducing her dose from once a day, to once every two days, to once every three days. Eventually, she ran out of medicine, and has been plagued by insomnia ever since. “The worst time was when I didn’t sleep for four days and three nights. I was so exhausted that I could hardly breathe, but I still couldn’t fall asleep. It’s an awful feeling. If a person goes too long without sleep, it can be life-threatening.”

[…] Suifenhe shares a land border with Russia. In 1999, the Suifenhe Sino-Russian Free Trade Zone was established. Xiao Fang remembers that in her childhood, Russians were a common sight on the streets of Suifenhe, and elementary and middle schools offered Russian language courses. “Over half of the people who live in this city have some sort of small business selling Russian products.”

[…] Starting in 2021, this border city has been seen as particularly vulnerable to imported cases of COVID-19. The intermittent lockdowns of the past year mean that no express delivery packages can be sent or received. Most of the stores along a street specializing in Russian goods have closed down since the pandemic began.

[…] There are constant rumors that “the lockdown will lift in the next few days,” raising people’s hope only to dash them again and again.

In this small city where news travels fast and can’t be hidden, Xiao Fang often hears about conflicts brought about by stagnant incomes and rising prices.

During a three-day period in which Suifenhe’s lockdown was temporarily lifted, Xiaofang saw people fleeing the city like they were “escaping from the zombie virus.” After those three days, Suifenhe once again entered a state of lockdown.

[…] There are many more small cities and towns just like Suifenhe, Ruili, and Dongxing, places experiencing pressure that we can scarcely imagine. According to the incomplete data available, at least 20 cities across the country have been under lockdown since late March.

[…] We hope that these small cities, besieged by the pandemic and suffering under lockdown, will be seen and remembered. They need our encouragement, and they need our help. [Chinese]

An essay by Weibo user 丁香园 (Lilac Garden), deleted from Weibo but archived by CDT Chinese editors, focuses specifically on the sacrifices that have been made by the residents of Ruili over the past two years. A portion of the article, titled “The Two-year Battle Against the Pandemic in the Border City of Ruili: Nine Lockdowns, and Not a Single Case of Transmission to Other Provinces” has been translated below. All of the names are pseudonyms.

Since January 26, 2020, Ruili has experienced a total of nine lockdowns, the longest lasting 35 days. The city itself was closed for 160 days, but in the outlying villages, checkpoints were set up at the entrance to each village, and residents were strictly prohibited from entering or leaving. Some were confined to their villages for as many as 300 days.

[…] Exhausted “grid workers” had to deal with homebound residents who had been subjected to hundreds of rounds of nucleic acid testing, resulting in a great deal of unnecessary friction.

[…] Ruili’s local medical system has been under pressure for quite some time. There are only two relatively large “secondary” hospitals (Ruili People’s Hospital and Jingcheng Hospital), supplemented by a few small maternity and pediatric hospitals and rural clinics.

[…] “Everyone is afraid to go to the hospital now. They just suffer through minor illnesses, and only go to the hospital if it’s a serious illness.” [Local restaurateur] Su Di’s mother works at Longchuan County Hospital. She said that the problem is that people from Ruili with serious illnesses cannot leave the area to get essential medical treatment.

“When controls were stricter, ambulances weren’t even allowed to exit the highway. There have been cases where pregnant women miscarried and severely ill people weren’t able to get lifesaving treatment.”

School attendance is also a long-standing problem. High school teacher Chen Yi and her third-year students have been living and eating meals together in their classroom for an entire year.

“Primary school students have been studying online for nearly three years. The first- and second-year junior high school students were recently transferred to a vocational junior high in a neighboring county. As for the third-year middle school and third-year high school students, they’ve pretty much been confined to campus all year. There aren’t enough dormitories, so they’ve repurposed some of the classrooms and put up some prefab buildings.”

[…] Frequent investigations and punishments have aggravated the already tense atmosphere in some small towns. On March 30 alone, the government of nearby Wanding township released the names of 18 villagers who were punished for violating pandemic control regulations. Most had committed minor infractions such as gathering at the entrance of the village to chat or play cards, or for leaving the village without permission.

Residents must wear N95 masks when entering supermarkets, government offices, or other crowded venues. Failure to wear a mask (or to wear a mask properly) can result in a fine of up to 200 yuan, and those deemed uncooperative may be detained.

This small town has given its all to fighting the pandemic, and it has not been responsible for spreading a single case of COVID-19 to other provinces.

But for the people of Ruili, “life before COVID” is but a distant memory. “Civil servants work as security guards, or feed pigs or harvest rice. Doctors and residents gather at the entrance of the village for the familiar daily ritual of nucleic acid tests. Teachers and students sleep in their classrooms. It’s as if we’ve always lived like this.”

[…] In the three years since the pandemic began, the resident population of Ruili has fallen from 500,000 to 100,000.

This border city that grew prosperous from tourism and the jade industry has now fallen silent, following the departure of the businesspeople, migrant workers, and Burmese who once came here to seek their fortunes.

[…] Many people are unaware that here, along the southwestern frontier of this nation, ordinary small-town life is a thing of the past. Yunnan has 25 border counties and cities that remain under stringent pandemic prevention controls. Nationwide, there are 136.

When our compatriots who have stood silent guard at the nation’s doorstep cry out, they need real help, tangible assistance—not just flowers and applause. [Chinese]

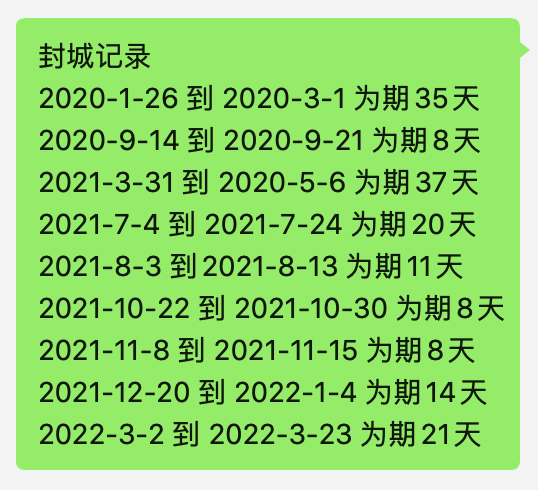

The following screenshot, widely shared on Chinese social media, shows a timeline of the lockdowns experienced by residents of Ruili, Yunnan Province:

January 26-March 1, 2020: 35 days

September 14-21, 2020: 8 days

March 31-May 6, 2021: 37 days

July 4-24, 2021: 20 days

August 3-13, 2021: 11 days

October 22-30, 2021: 8 days

November 8-15, 2021: 8 days

December 20, 2021-January 4, 2022: 14 days

March 2-23, 2022: 21 days

source https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2022/05/translation-long-lockdowns-in-chinas-border-towns/

No comments:

Post a Comment