It has been nearly one year since a viral video of a woman shackled and chained in a freezing shed in Dongji Village (Feng County, Jiangsu Province) provoked widespread outrage among the Chinese public and triggered an investigation into human trafficking that resulted in 17 local officials being sacked or otherwise punished for “dereliction of duty.” Investigators claimed that the woman was named Xiaohuamei, hailed from Yunnan Province, and suffered from schizophrenia; she had apparently been trafficked several times before being sold into Dongji Village, where she was married to a man named Dong Zhimin.

But a lack of information about the current health and whereabouts of the woman and her eight children has made many concerned citizens uneasy, and previous attempts to visit either her or the children have failed. In February of 2022, feminist activists Wuyi and Quanmei tried to visit the woman in the hospital and were harassed by local police, detained, mistreated during detention, and had their social media accounts blocked.

On January 10, the Beijing-based pioneering defense lawyer Li Zhuang attempted to visit the woman and her eight children in their village prior to the Lunar New Year. The purpose of the visit, made at the behest of his legal colleagues, was to check on the childrens’ welfare and bring them gifts and donations. But when Li Zhuang and his driver arrived at the village, they found the entrance heavily guarded. After attempting to register with the guards and reason with the police, they were given the run-around, refused permission to enter, and forced to turn back.

CDT Chinese editors have archived Li Zhuang’s now-deleted post detailing his attempted visit: “Trip to Feng County: The Village Where the Shackled Woman Remains Under Strict Guard” is translated in full below. Other posts incorporating the same content also appear to have been scrubbed by censors.

@张新年律师 (“Zhang Xinnian Lüshi,” “Attorney Zhang Xinnian”): I never imagined that after all this time, the village where this tragedy-stricken mother and her eight children live would still be kept under such close guard, supposedly to prevent “suspicious persons” from entering the village! May we ask why the village even considers this necessary? How is this not another form of “shackling”? Why prevent people from visiting them and showing them some love and compassion? Are they not deserving of the right to be helped by people who care about them? It’s absolutely unfathomable! For more details, see Li Zhuang’s (@李庄) “A Trip to Feng County,” below. ↓

A Trip to Feng County

It has been over a year since the incident of the chained and shackled woman first surfaced, and a bevy of cadres—the county Party secretary, county magistrate, township Party secretary and mayor, deputy director of the local PSB, deputy director of the local propaganda department, as well as officials from the local family planning office and the Women’s Federation—have been subject to varying degrees of punishment.

But what happened to the shackled woman? How are her eight children doing now? Lunar New Year is fast approaching, and my legal colleagues and I are very concerned about them. Many people have entrusted me with donations of cash and supplies, and have asked me to pay them a visit and check on them.

Yesterday, we traveled from Beijing to Xuzhou to Feng County, where we checked into a hotel.

After breakfast this morning, we set out for Dongji Village. We left our hotel in Feng County, and passed through Lizhuang Village, Huankou Township. It’s less than a 30-kilometer (19-mile) trip, and it wasn’t long before we arrived.

Dongji Village is located along a small country road, about 400 to 500 meters (approximately 440 to 550 yards) away from the main highway. Here in northern Jiangsu, despite the sunshine and blue skies, the winter wind is as bitterly cold as it is up north, and all the trees are bare. Under the winter sun, northern Jiangsu’s Yellow River floodplain seems to stretch on for eternity.

From a distance, we could see that there were people guarding the entrance to the village, and that roadblocks had been placed haphazardly in the middle of the road. Cruising across the unobstructed plain in our large black SUV, we felt particularly conspicuous.

Someone began walking down the middle of the road toward us, but the road was so narrow it was impossible to make a U-turn, so all we could do was steel ourselves and keep driving forward. Before we had even reached the roadblocks, a village cadre rushed forward, stood in front of our car, and gestured for us to stop. There was something about his style that reminded me a bit of Dong Zhimin [the husband of the shackled woman].

“Why are you here?”

“To see Old Dong’s family.”

“Which one? Most people in our village have the last name Dong.”

“Dong Zhimin’s family, the one with eight children. We’re here to pay them a visit for Lunar New Year.”

“You’ll have to show your I.D. card and sign the register.”

When the driver took out his I.D. card and went to sign the register, I got out of the car along with him. There was a series of metal buildings (modified shipping containers) along the side of the road. They were checkpoints, manned around the clock.

Another village cadre led us into the modified shipping container and started the registration process.

“I wanted to visit last year,” I told him, “but it was tough because of the pandemic. Now that the pandemic policy has changed, why are you still arbitrarily setting up roadblocks to the village?”

“Orders from above. You have to register.”

“You’re probably the only village in the whole country that requires people to register with their I.D. to get in.”

The village cadre remained silent.

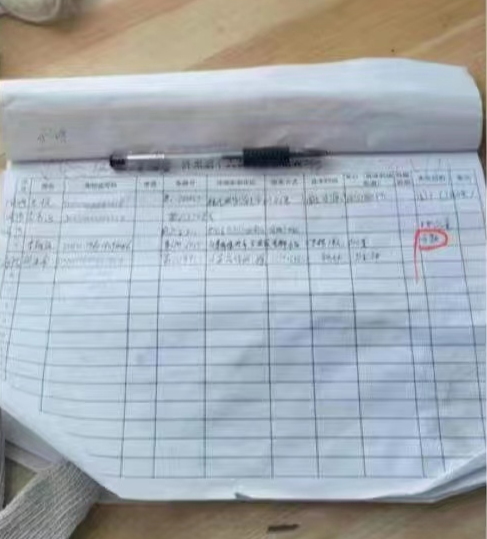

As he took our I.D. cards and started to register us, I craned my neck and glanced around. The A4-sized registration ledger was grease-stained, but it contained a wealth of content about previous visitors: full names, identity card numbers, and “purpose of visit.” There were also notations marking some visitors as “suspicious.” “Suspicious” in what sense, I wondered. It probably meant people like us.

ALT text: A tattered ledger shows columns listing dates, purpose of visit, names, I.D. card numbers, and other personal information about visitors to the village.

After registering, we asked if we could enter the village, but we were once again denied permission.

“Didn’t you just say that we could enter after registering?”

“We have to wait for permission from our boss.”

“So if your boss doesn’t give permission, we can’t go in?”

“That’s right.”

“We’re just here out of sympathy for that shackled woman’s eight children. All we want is to check how they’re doing, and then we’ll leave.”

“Let’s see if you get permission first.”

“If something similar had happened to your family, we’d be just as sympathetic. We’d want to pay you a visit, too.”

The village cadre kept his head bowed and said nothing.

Just then, a white car drove up, and two village cadres went out to intercept it and speak to the driver.

“Why are you here?”

“I’m going to my father-in-law’s house.”

“What’s your father-in-law’s name?”

“Dong …”

I stepped forward and asked, “He’s not even allowed to go to his own father-in-law’s house?”

“Mind your own business!” Apparently the village cadre thought I was being too nosy.

Another village cadre was on the phone, reporting on our situation: “Beijing license plates … two people … I heard there are more vehicles on the way …”

Not long after that, a group of auxiliary police officers showed up riding electric motorcycles.

We kept asking if we could go into the village, explaining over and over again that all we wanted to do was pay a brief visit to those eight children, but our requests were denied.

Seeing that it was approaching noon, and realizing that the situation was futile, we decided to drive back to Feng County.

But when we started our engine, we discovered that a white sedan had stopped in the middle of the road, blocking our retreat.

“You won’t let us go into the village to visit the kids, but you won’t let us leave, either. You’re unlawfully restricting our freedom of movement!” We protested loudly. “That’s a crime!”

One of the village cadres stood directly in front of our car. “Go ahead and leave,” he said tauntingly, “We’re not stopping you.” I pushed him out of the way and signaled to the driver to get ready to speed away. Suddenly, we found ourselves surrounded by a large group of men.

I promptly dialed 110 to call the police. A quarter of an hour later, the police still hadn’t shown up.

Later, I noticed a poster on the outside of the guardhouse, advertising a hotline number for the [non-emergency] community police service. I called the number, but there was no answer, and no one had showed up yet in response to my 110 call.

I dialed 110 a second time.

“There’s been a physical altercation at the entrance to Dongji Village. Why is it taking the police so long to respond?”

“The police station has already been notified, and they’ll arrive as soon as they can.”

“And how soon is that?”

……

About half an hour after my initial call, the first police car arrived.

The police started by asking for our full names and I.D. card numbers, and then asked where we’d come from and what we were doing here.

We answered each of their questions in turn, and reiterated that we had only come here to visit those eight children and offer them our best wishes for Lunar New Year.

“Have you been authorized to visit?” asked the police officer.

“Does a citizen need authorization to show their concern for another citizen?”

The policeman said nothing.

I pointed to the large group of men surrounding us. They were illegally restricting our freedom of movement by not allowing us into the village and not allowing us to leave. I also pointed to the white sedan stopped in the middle of the road, blocking our retreat.

“Wait a moment, just wait a moment,” said the policeman, “and someone will be here to explain.”

“We don’t need anyone to explain. You’re the police, and this is a case of public security. Are you saying there’s someone else capable of intervening in and obstructing police business?”

As we were arguing, a second police car arrived, and a man who looked like a higher-ranking local cadre got out. Once again, we were asked where we’d come from, where we were going, and what we were doing.

“We’ve come from Beijing to visit the shackled woman and her eight children. With Lunar New Year coming up, a lot of people have asked us to visit and offer them some support.”

“Well, in that case, you’ll need to report to the county Party committee propaganda department.”

“We’re private citizens, here on our own initiative. We’re not from the People’s Daily or CCTV or someplace like that. Why should we report to them?”

“Because anyone who comes here needs to report to them!”

We continued arguing, to no avail.

“All right, then we’ll go to the county Party committee. Can we go there now?” I asked the policeman.

“Yes.”

“But their car is still blocking us.”

“Whose car is this?” shouted the police officer. “Whose car? Move it!”

That village cadre took his sweet time climbing into the car and driving away.

At noon, with nothing to show for our visit, we left.

The fate of the shackled woman and her eight children will continue to haunt me. [Chinese]

The CDT Chinese site features a detailed archive of content related to the Xuzhou woman’s case, arranged both chronologically and by topic (users can toggle between the two arrangements).

source https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2023/01/translation-li-zhuangs-trip-to-feng-county-where-shackled-woman-remains-under-strict-guard/

No comments:

Post a Comment