Modern art museum Shenzhen, by Dietertimmerman (CC BY 2.0)

source https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2023/01/photo-modern-art-museum-shenzhen-by-dietertimmerman-2/

Two months after the spontaneous nationwide protests that broke out in response to a deadly fire in Urumqi and draconian pandemic controls, an unknown number of peaceful protesters remain in detention on charges of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” or “gathering a crowd to disrupt public order.” Human rights groups and others have called for the release of the “A4” or “blank paper” detainees (so called because of the blank sheets of A4 paper used as protest signs during the gatherings), some of whom have been threatened, physically abused, or denied access to legal representation while in detention.

Chinese Human Rights Defenders has compiled a list of known detainees and issued a call to release all of the “blank paper” protesters:

At the time of this press release, there are names of 30+ people who were taken into custody; we estimate that at least 100+ people have been detained, and some of them have been simply released or released on “bail pending trial” (取保候审). Under Chinese law, defendants released on “bail pending trial” can see the charges against them dropped if they do not commit further violations of the law, but often remain under close police surveillance for one year. In other cases, involving unknown names or other details, family members are reluctant to go public out of the fears for retaliation from the Chinese government. [Source]

Several of those arrested for attending the peaceful protest held in late November at Beijing’s Liangmahe Bridge are current or former journalists. “By arresting and detaining four reporters for the simple fact of being present at the place of the protests, the Chinese regime has sent one more chilling message to those who believe that factual information should be reported even when it contradicts the official narrative,” noted RSF East Asia bureau head Cédric Alviani. “The regime should release [the remaining] two reporters as well as all other journalists and press freedom defenders detained in China, and to drop all charges against them.”

Particularly worrying is the fact that security forces seem to have zeroed in on young female protesters, interrogating them about their involvement with feminism, LGBTQ+ issues, NGOs, book clubs, and foreign study or travel. A recent report by CNN details this concerning trend:

People who know [the detained women] echoed a sense of confusion over the detentions in interviews with CNN, describing them as young female professionals working in publishing, journalism and education, that were engaged and socially-minded, not dissidents or organizers.

One of those people suggested that the police may have been suspicious of young, politically aware women. Chinese authorities have a long and well-documented history of targeting feminists, and at least one of the women detained was questioned during her initial interrogation in November about whether she had any involvement in feminist groups or social activism, especially during time spent overseas, a source said.

All felt the detentions indicated an ever-tightening space for free expression in China. [Source]

A thread of people arrested for and charged with “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” – a catch-all offence criminalising peaceful dissent in China – for their participation in the 2022 White Paper protests:

— Sophie Mak (@SophieMak1) January 27, 2023

Li Siqi 李思琪 is a freelance journalist and photographer with a master’s degree in cultural studies from @GoldsmithsUoL. She was arrested on 18 Dec for participating in a vigil in Beijing on 27 Nov. She spent her 27th birthday in custody. pic.twitter.com/TFzrQb49pA

— Sophie Mak (@SophieMak1) January 27, 2023

Cao Zhixin 曹芷馨 works as an editor at Peking University Press. She was arrested on 23 Dec for participating in a vigil in Beijing on 27 Nov. She had plans to do a PhD on Chinese environmental history in the US this year. pic.twitter.com/hctThmzJdw

— Sophie Mak (@SophieMak1) January 27, 2023

Another A4 protester in Beijing, #QinZiyi, have been forcibly disappeared for a week. She was briefly arrested in early Dec after the protest. Qin is a former Caixin journalist, with a bachelor of law at Tsinghua Uni, two master’s degrees from UChicago and HKBU. #FreeA4Protester pic.twitter.com/zUsOPb0o4q

— Zuowang 左望 (@zuowang51) January 1, 2023

Ziyi Qin, a former student of U Chicago, was recently detained. She’s a good writer, a passionate journalist, a free mind with a loving soul. Hope there would be more universities like @UChicagoCEAS showing their support for current/former students like Ziyi❤️ #白纸抗议 pic.twitter.com/OFM2SM2SHF

— Jing Wang (@JingWang0815) January 20, 2023

Some of the protesters wrote letters or recorded videos prior to being detained. Helen Davidson of The Guardian reported on a video by Cao Zhixin, a 26-year-old editor at Peking University Press, who was summoned by police and later detained after she and some friends attended a November 27 vigil in Beijing:

[Cao Zhixin] said she recorded the video after several friends were detained. She gave it to unnamed friends with instructions to publish it if she were arrested.

“When you see this video I have been taken away by the police for a while, like my other friends,” the video says.

Cao said her friends were made to sign blank arrest warrants, without criminal accusations listed, and that police refused to reveal the location of their detention. [Source]

At the New York Times, Vivian Wang and Zixu Wang described the arrests of the young women, none of whom are seasoned activists, as a way for the Chinese government to deflect from the underlying dissatisfaction that fueled the protests, perhaps pin the blame on “hostile foreign forces,” and deter others who might have drawn inspiration from the demonstrations:

“The Chinese government has to look for an explanation that fits their logic, and they don’t believe that people organize on their own, according to their own political feeling. There must be a ‘black hand,’” [said Lu Pin, a Chinese feminist activist who now lives in the United States]. “In China, feminism is the last active, visible social movement.”

[…] Ms. Lu […] said the police’s evident focus on people who were not prominent organizers, or even apparently part of any larger group, underscored how the authorities had decimated civil society.

“After all the repression, in the eyes of the police, these people have become the most threatening forces,” she said. “These communities that normally would not be considered political — people eating together, watching movies, talking about art — at key times, these can have the potential for political activation.” [Source]

On the Chinese internet and social media, discussion of the protests and the detained protesters is heavily censored, although netizens have attempted to share related content and updates. CDT Chinese editors have archived two now-deleted posts that sought to circumvent censorship by not including the names of specific female detainees, referring to them only by “she” or “them.” Both were shared and commented on before eventually being taken down.

The first post, from Weibo user @宪跬法律 (Xiankui Falu), describes a December 29 visit made by an attorney to a young woman in detention: “This afternoon, at a detention center 100 kilometers (60 miles) away, I was able to meet with a brave young woman.” Although the young woman is not named, those who commented on the post speculated that it could be one of the detained A4 protesters, or perhaps even Wuyi, a feminist activist who was detained after she attempted to visit a woman in Jiangsu who had been chained and shackled in a shed by her husband. A partial translation of the post and some of the comments appear below:

Lastly, I asked her if she had anything to say to her parents.

She said, “I hope my parents will look after their health and eat more fruit. I’ll be able to adjust to being here, so please tell them not to worry. … My mom knows that I did nothing wrong.” As she said this, she choked up a bit.

(Selected comments):

举报人的离奇遭遇:I don’t know who this young woman is, but we can see from lawyer Zheng’s Weibo post that she is a brave young woman, and I hope that she will regain her freedom soon!

YZWB001:These women are a ray of light for 2022.

土猫晴空月:Not only didn’t she do anything wrong, she is the most courageous person among us, braver than all of us combined!

企鹅饲养员一号机:So many brave people were forcibly disappeared. Now that the New Year is upon us, are they okay? [Chinese]

The second post is a now-deleted essay, written in response to the story of the lawyer’s visit to the detained woman. Published by WeChat account “声声不息的我们” (Shengsheng Bu Xi De Women, “We Who Will Not Be Silenced”), the essay draws a parallel between the unnamed young woman in detention and all of the brave young people who spoke out for justice in 2022:

Because of you [young people], the suffering that we have endured during these three years of the pandemic seems to have some small shred of meaning after all. It was you who, by boldly speaking your minds, won back a modicum of dignity for every person who has been harmed and enslaved. [Chinese]

January 27 is designated by the U.N. as International Holocaust Remembrance Day, on the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz concentration camp, to commemorate the Jewish victims of the Nazi genocide. The world’s resolve to prevent such crimes against humanity from happening again appears to have fallen short in the case of Xinjiang, argued Uyghur activists this month. Concentration camps continue to operate and the Chinese state continues to subject the region’s ethnic minorities to grave human rights abuses, both inside and outside of the camps, while attempting to obfuscate the reality to foreign observers. During this time of remembrance, Uyghurs challenge the international community to confront the true meaning of “Never Again.”

New testimonies reveal the dire state of affairs in Xinjiang. Earlier this month, Kazakh activist and former journalist Zhanargul Zhumatai sent a plea for help from her home in Urumqi. Previously detained in a concentration camp for two years and 23 days, allegedly for having Instagram and Facebook on her phone, she now receives almost daily calls from local authorities. Christoph Giesen and Katharina Graça Peters from Der Spiegel shared her story this week and highlighted the persistent harassment she has faced since her release:

She laments that she has constantly been the subject of intimidation and harassment since her release.

“I’m not treated like a human by the officers, I’m treated like a dog on a short leash. My lightness and joie de vivre are gone. I used to go out a lot, I danced, I sang. But I haven’t felt like doing anything since I was in the camp. When I go shopping, I get stopped at a checkpoint. When I tell others what has happened to me, I get called an agent or a spy.”

[…] “Since I came back from the camp, I’ve just been vegetating. Instead of dying without having fulfilled my purpose, I am telling my story now. At least then there will be some meaning when I die.” [Source]

Asim Kashgarian from VOA interviewed a Uyghur man who recently left China and summarized the constant fear and arrests that plague many Uyghurs’ lives after being released from concentration camps:

Another trend in 2022 in Xinjiang is that the Chinese government never stopped arbitrary arrests of Uyghurs and even started rearresting Uyghurs who had gone through reeducation in the past. I had a friend who was a lecturer at a university. He had been arrested twice before 2022. In the spring of 2022, he was arrested for the third time, and his family never heard of him again. If I sum up life in 2022 for Uyghurs in Xinjiang, it’s the normalization of the combination of fear and hopelessness. [Source]

Some Uyghurs were also rounded up by authorities after the recent wave of nation-wide protests. A U.S.-based Uyghur man named Kewser Wayit spoke out earlier this week, calling on Chinese authorities to release his 19-year-old sister Kamile Wayit, who was detained on December 12 after posting a video related to the A4 protests. Kamile was studying preschool education at a university in Hebei, and the official reason for her detention is unknown. Kewser also stated that their father had been held in a concentration camp between 2017 and 2019, and their cousin Zulpiqar Qudret, a Shanghai Jiaotong University computer-science student, went missing during the summer of 2022 for “using foreign news software” and remains in detention today.

This week, Tomomi Shimizu, a well-known writer and illustrator in Japan, released an English translation of her new manga booklet portraying the experience of Qelbinur Sidiq, also known as Kalbinur Sidik, a 53-year-old Uzbek woman from Xinjiang who was forced to teach Mandarin in a concentration camp. Sidiq, who had previously been subjected to a forced abortion and sterilization under a government campaign to suppress birthrates among Muslim women in the region, said that she witnessed rape and other forms of torture in the camps.

What has Happened to me ~Testimony of an Uzbek Woman~ (1/7)#Uyghur #stopuyghurgenocide #China #CCPChina pic.twitter.com/syw6cJPFos

— 清水ともみ (@swim_shu) January 25, 2023

What has Happened to me ~Testimony of an Uzbek Woman~ (3/7)#Uyghur #stopuyghurgenocide #China #CCPChina pic.twitter.com/B6kwoTm8Zc

— 清水ともみ (@swim_shu) January 25, 2023

What has Happened to me ~Testimony of an Uzbek Woman~ (5/7)#Uyghur #stopuyghurgenocide #China #CCPChina pic.twitter.com/VkkBOQDrE0

— 清水ともみ (@swim_shu) January 25, 2023

What has Happened to me ~Testimony of an Uzbek Woman~ (6/7)#Uyghur #stopuyghurgenocide #China #CCPChina pic.twitter.com/bG6RBAdu2N

— 清水ともみ (@swim_shu) January 25, 2023

On Friday, Filip Noubel from Global Voices interviewed Gene Bunin, founder and curator of the Xinjiang Victims Database, who described the situation in Xinjiang as dire, with many people still in arbitrary detention or traumatized by the state’s destruction of their lives:

There hasn’t been much noticeable change since 2019, when many of the extrajudicial camps do appear to have been phased out, with many in them released or transferred into “softer” forms of detention (forced job placement, strict community surveillance). Those who were detained in 2017 and 2018 through the nominal judicial system and sentenced to long prison terms — probably half a million people — have continued to serve their terms with no news of anyone being pardoned or released ahead of schedule. International coverage has not focused sufficiently on this issue of mass sentencing and, consequently, the Chinese authorities have had no reason to make concessions. So, the people imprisoned remain imprisoned, with the average sentence length approaching ten years.

[…I]t would be wrong to conclude that things are significantly better now and that people can relax. Not only because of the hundreds of thousands who remain incarcerated and whose judicial processes remain inaccessible and unknown, but also because the region is still a vacuum. Furthermore, the accumulated negative social effects and mental health issues caused by family separation, continued internment, and unaddressed trauma will only continue to worsen with each year that passes. Because the fundamental issues — masses incarcerated, lack of communications, and inability to come and go freely — all remain unresolved. [Source]

Reporting on “China’s New Anti-Uyghur Campaign” in Foreign Affairs this week, James Millward noted that the CCP’s campaign of repression in Xinjiang remains at least as intense now as it was at the height of internments in 2019, although it has taken on a subtler form:

[The CCP’s public removal of certain “graduating” detainees from the camps in 2019] was largely cosmetic, and most of the internees have not been freed. Many of the camps have simply been converted into formal prisons and detainees given lengthy prison sentences, like several hundred thousand other non-Han people who have been imprisoned since the start of the crisis. Over 100,000 other internees have been transferred from camps to factories in Xinjiang or elsewhere in the country. Some Uyghur families abroad report that their relatives are back home but under house arrest. And Beijing has also been forcing tens of thousands of rural Uyghurs out of their villages and into factories under the guise of a poverty alleviation campaign. Today, the total numbers of non-Han Chinese people in coerced labor of one form or another may well exceed the numbers interned in camps from 2017 to 2019.

[…] The infrastructure of control that made southern Xinjiang look like a war zone a few years ago—intrusive policing, military patrols, checkpoints—is less visible now. But that is because digital surveillance systems based on mobile phones, facial recognition, biometric databases, QR codes, and other tools that identify and geolocate the population have proved just as effective at monitoring and controlling local residents. [Source]

Uyghur leaders in exile have drawn a clear connection between the ideals of Holocaust Remembrance Day and the overlooked plight of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang. In an op-ed for The Hill this week, former president of the Uyghur-American Association Kuzzat Altay issued a powerful reminder: “Never Again” requires action. It requires punishment of the very thing the world declared it would never allow again after the Holocaust of the Jews in World War II. It requires prioritizing human beings over money. It requires acting now, not tomorrow.” In The Diplomat on Friday, executive director of the Uyghur Human Rights Project Omer Kanat reflected on the significance of Holocaust Remembrance Day and the need for Jewish-Uyghur solidarity:

On International Holocaust Remembrance Day, we remember the singular experience of the Jewish people, targeted for unspeakable horrors on an industrial scale. Solemn remembrance of the Holocaust is important for all humanity. And for Uyghurs, in our current crisis, “Never Forget” and “Never Again” have a direct and profound meaning. In the spirit of remembrance and of action, I express my gratitude to the Jewish community and to the many others who are advocating for universal human rights and continuing to demand “Never Again” in defense of the Uyghur people. [Source]

Meanwhile, the Chinese government has continued its attempts to present a sanitized version of Xinjiang to the outside world. Earlier this month, the region’s Party chief Ma Xingrui welcomed 30 Islamic scholars from 14 Muslim countries to Ürümchi, where the group visited several mosques and an anti-terrorism exhibition. The Global Times parroted their praise for the CCP’s policies and criticism of “Western lies,” and the event was touted on Twitter by numerous Chinese–state–affiliated accounts.

Uyghurs strongly condemned the cowardice of the visiting Muslim leaders and their willingness to be co-opted by the CCP for propaganda purposes. “This is a desperate attempt by the Chinese to change the narrative, create a softer image in Muslim societies and project a more lovable image around the world,” said Nury Turkel, a Uyghur-American lawyer and chair of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. Ruth Ingram at The China Project shared other critical reactions to the Muslim leaders’ visit, including a comparison to Nazi apologists during the Holocaust:

Rushan Abbas, the director of Campaign for Uyghurs, called on Muslim leaders then to redress the “slap in the face” against her people and questioned the authenticity of a body that appeared to be betraying them. “Muslim leaders must defend their faith by speaking out against injustice, oppression, and tyranny,” she said.

This year’s visit was described by Rushan Abbas as a tool to “whitewash and deny” the “ongoing campaign of colonialism, genocide, and occupation of East Turkestan while actively waging war on Islam and criminalizing the entire normal practice of religion as illegal Islamic activities.”

U.K.-based Sheldon Stone, a prominent supporter of the Uyghur cause and a Times of Israel blogger, commenting on the recent delegation, said, “This is like the heads of the Jewish communities in 1940s having tea with Hitler in the Berghof, after a tour of the Theresienstadt show camp, to celebrate the ‘resettlement of the Jews.’” [Source]

Last week, the Chinese government announced that the country’s population had declined for the first time in decades, setting off a cacophony of alarm bells among those concerned about China’s demographic destiny. Chinese women, by contrast, have largely ignored the hoopla. As demonstrated in numerous commentaries over traditional and social media this week, women have little interest in participating in the state’s latest pro-natalist project.

“[I]n terms of China’s population governance,” explained Yun Zhou, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan’s Department of Sociology, “women’s bodies and women’s reproductive labor in different ways are being utilized or co-opted as the ways in which to achieve […] the state’s demographic, political or economic growth.” But many women have had enough. Some are explicitly linking their aversion to childbearing with their poor treatment by society and the government, which Yuan Yang at The Financial Times described as a women-led “birth strike”:

Feng Yuan, a veteran Chinese feminist activist, sees an opportunity in this moment: “The government knows it has to be better to women; yet it doesn’t listen to them.” The term “birth strike”, as used by Korean and American feminists such as the author Jenny Brown, is a way of turning low fertility into a rallying call for better conditions. In its focus on gross domestic product growth, Beijing has forgotten that the economy is made up of humans, who also need producing.

So far it has expected this work to be done out of duty. “The CCP’s official speeches emphasise that women should be responsible for caring for the young and old,” says Yun Zhou, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Michigan.

Such speeches are useless in [e]ffecting a rise in birth rates. If over two millennia of Confucian teaching about the woman’s place in the home won’t do it, I don’t think any publicity campaign the all-male Politburo of the Communist party comes up with in 2023 will. As a friend explained: “Women who grow up in China have developed immunity to being endlessly nagged to get married and have kids.” [Source]

Vibrant debates have taken place on Chinese social media in the wake of the government’s announcement. What’s On Weibo documented negative online reactions towards opinion leaders in state-media outlets presenting solutions to the population crunch and calling on people to get married and have children in order to “contribute” to raising the country’s birth rates. Netizens pointed out that some of these propositions are merely treating people as “tools,” and that one such “opinion-leader” had a forty-something daughter who is allegedly not married herself. At The Washington Post, Christian Shepherd and Lyric Li reported on the hashtags and online slang used to describe women’s feeling of exploitation:

In the days since the statistics put the spotlight back on [the population] issue, hashtags saying “is it important to have descendants?” or the “reasons you don’t want to have a child” have drawn debate on Weibo, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter. Some users took issue with (often male) commentators who urged more births, responding that, while having a child should be everyone’s right, it isn’t anyone’s responsibility.

[…] Others used the recent neologism “renkuang,” which combines the characters for human and for a mine or mineral deposit, to voice displeasure at being treated like a raw resource exploited for economic ends.

The term — which can perhaps be translated as “humine” — joins a growing lexicon of China’s disaffected youth, alongside “lying flat,” “let it rot” and “involution,” all of which are used to capture frustration with government expectations of hard work and sacrifice without the offer of rewards. [Source]

Women are taking a stand against societal expectations that they should shoulder the disproportionate burden of childbearing. “It’s a very realistic assessment for women to say ‘I haven’t met a man that will support me in this task of combining work with child care or elder aged care and so I just won’t marry,'” said Doris Fischer, chair of China Business and Economics at the University of Würzburg. Simon Leplâtre from Le Monde described how some women are unwilling to make the sacrifice to have children in an environment that they perceive as pressuring them into subservience:

The situation makes Pepper feel bitter: “It seems like there will always be someone from the upper classes to wring out the people from the lower classes to consolidate their economic interests. So unless I manage to climb the social ladder, my child will also be a member of the oppressed class,” she predicts.

[…] On social media, Chinese women are critical of being treated as mere wombs by their husbands and in-laws, who expect them to have a child, and if possible, a son. “I’m not sure I’m ready for such a sacrifice,” said Yaqing (her first name has been changed). “For me, getting married means accepting to live with the Chinese patriarchal gender culture. In general, Chinese men look for fertile, obedient women under 30 that are not too ambitious so they can sacrifice everything for the family. Me, I couldn’t.” [Source]

Women’s disproportionate “burden of care” for children and family members is an added disadvantage in the workplace. “[E]mployers are discriminating against women as [they] are perceived to have more care burdens and are thus deemed as secondary workers,” said Yige Dong, assistant professor in the department of global gender & sexuality studies at SUNY Buffalo, who noted that such labor discrimination disincentives childbearing. Even as the Chinese government considers subsidizing I.V.F. procedures to help couples have children, labor rights remain a major obstacle. One woman told The New York Times: “The most stressful thing about I.V.F. is that I lost my job,” and since her operation, “I feel sick and dizzy all the time.” Lucas de la Cal from El Mundo shared the perspectives of other women who refuse to sacrifice career ambitions and economic stability in order to have children:

The extreme restrictions on births in China have marked several generations like Xiao [Lu]’s. “We have gone from women being forced to have an abortion or having to abandon the baby if it was the second one we had, like some cases I know of, to now being asked to have many children for the good of our country. But now we are the ones who don’t want to”.

[… Xiao] is 34 years old, single, a businesswoman, and does not have or want to have children. She says that, out of her group of urban friends from Guangzhou, who are around the same age as her, only one of them had a child last year. “Having children now would cut our career progression in a country where there is excessive competition, where women are tested much more than men, and where we have to make twice as much effort for everything. It is normal that now there are many who delay motherhood or give it up completely, because supporting a baby now is also much more expensive than before and not everyone has the means to do so,” she explains. [Spanish]

The Chinese state seems stubbornly committed to restricting women’s roles to mere “child-bearers.” During the China Media Group’s annual Spring Festival Gala last weekend, the women participants were reduced to scripted stereotypes based on traditional family values of motherhood, as highlighted in a now-deleted post from the WeChat account 荡秋千的妇女 (Dang Qiuqian de Funu, or “Women on Swings”—a female writers’ collective). The authors of the post stated: “In this Spring Festival Gala, women are missing. Their labor is invisible; their image has been defined for them.” In hope of a more equitable future, they called for women to be respected as individuals independent of their marital or familial status:

We look forward to when women will be able to take center stage—no longer only in subsidiary roles as mothers, daughters, or wives, but as full human subjects in their own right, making their voices heard and telling their own stories.

We look forward to when women from all walks of life will enjoy more decision-making authority and be able to help women as a whole to emerge from the shadows, no longer defined by others or hidden from view.

We hope there will come a day when, upon that stage, we will see not only that women exist, but also what their existence is like. [Chinese]

In addition to circumscribing the role of women, the Chinese state and state-media have been dismissive of, and even antagonistic to the role of non-traditional families in contemporary Chinese society. A recent essay posted to the WeChat account 流放地 (Liufangdi, “Place of Exile)” notes that by utterly ignoring the diverse range of families in China today, the Spring Festival Gala could be said to be “extremely hostile to non-traditional families”:

The Spring Festival Gala is growing increasingly out of touch with real life. Nowadays, there are large numbers of divorced families, single-parent families, DINK (“double income, no kids”) families, unmarried mothers, LGBTQ+ families, women who are married to gay men, and so on, but none of these groups are allowed to appear on the Spring Festival Gala stage. [Chinese]

With additional translation by Cindy Carter.

It has been nearly one year since a viral video of a woman shackled and chained in a freezing shed in Dongji Village (Feng County, Jiangsu Province) provoked widespread outrage among the Chinese public and triggered an investigation into human trafficking that resulted in 17 local officials being sacked or otherwise punished for “dereliction of duty.” Investigators claimed that the woman was named Xiaohuamei, hailed from Yunnan Province, and suffered from schizophrenia; she had apparently been trafficked several times before being sold into Dongji Village, where she was married to a man named Dong Zhimin.

But a lack of information about the current health and whereabouts of the woman and her eight children has made many concerned citizens uneasy, and previous attempts to visit either her or the children have failed. In February of 2022, feminist activists Wuyi and Quanmei tried to visit the woman in the hospital and were harassed by local police, detained, mistreated during detention, and had their social media accounts blocked.

On January 10, the Beijing-based pioneering defense lawyer Li Zhuang attempted to visit the woman and her eight children in their village prior to the Lunar New Year. The purpose of the visit, made at the behest of his legal colleagues, was to check on the childrens’ welfare and bring them gifts and donations. But when Li Zhuang and his driver arrived at the village, they found the entrance heavily guarded. After attempting to register with the guards and reason with the police, they were given the run-around, refused permission to enter, and forced to turn back.

CDT Chinese editors have archived Li Zhuang’s now-deleted post detailing his attempted visit: “Trip to Feng County: The Village Where the Shackled Woman Remains Under Strict Guard” is translated in full below. Other posts incorporating the same content also appear to have been scrubbed by censors.

@张新年律师 (“Zhang Xinnian Lüshi,” “Attorney Zhang Xinnian”): I never imagined that after all this time, the village where this tragedy-stricken mother and her eight children live would still be kept under such close guard, supposedly to prevent “suspicious persons” from entering the village! May we ask why the village even considers this necessary? How is this not another form of “shackling”? Why prevent people from visiting them and showing them some love and compassion? Are they not deserving of the right to be helped by people who care about them? It’s absolutely unfathomable! For more details, see Li Zhuang’s (@李庄) “A Trip to Feng County,” below. ↓

A Trip to Feng County

It has been over a year since the incident of the chained and shackled woman first surfaced, and a bevy of cadres—the county Party secretary, county magistrate, township Party secretary and mayor, deputy director of the local PSB, deputy director of the local propaganda department, as well as officials from the local family planning office and the Women’s Federation—have been subject to varying degrees of punishment.

But what happened to the shackled woman? How are her eight children doing now? Lunar New Year is fast approaching, and my legal colleagues and I are very concerned about them. Many people have entrusted me with donations of cash and supplies, and have asked me to pay them a visit and check on them.

Yesterday, we traveled from Beijing to Xuzhou to Feng County, where we checked into a hotel.

After breakfast this morning, we set out for Dongji Village. We left our hotel in Feng County, and passed through Lizhuang Village, Huankou Township. It’s less than a 30-kilometer (19-mile) trip, and it wasn’t long before we arrived.

Dongji Village is located along a small country road, about 400 to 500 meters (approximately 440 to 550 yards) away from the main highway. Here in northern Jiangsu, despite the sunshine and blue skies, the winter wind is as bitterly cold as it is up north, and all the trees are bare. Under the winter sun, northern Jiangsu’s Yellow River floodplain seems to stretch on for eternity.

From a distance, we could see that there were people guarding the entrance to the village, and that roadblocks had been placed haphazardly in the middle of the road. Cruising across the unobstructed plain in our large black SUV, we felt particularly conspicuous.

Someone began walking down the middle of the road toward us, but the road was so narrow it was impossible to make a U-turn, so all we could do was steel ourselves and keep driving forward. Before we had even reached the roadblocks, a village cadre rushed forward, stood in front of our car, and gestured for us to stop. There was something about his style that reminded me a bit of Dong Zhimin [the husband of the shackled woman].

“Why are you here?”

“To see Old Dong’s family.”

“Which one? Most people in our village have the last name Dong.”

“Dong Zhimin’s family, the one with eight children. We’re here to pay them a visit for Lunar New Year.”

“You’ll have to show your I.D. card and sign the register.”

When the driver took out his I.D. card and went to sign the register, I got out of the car along with him. There was a series of metal buildings (modified shipping containers) along the side of the road. They were checkpoints, manned around the clock.

Another village cadre led us into the modified shipping container and started the registration process.

“I wanted to visit last year,” I told him, “but it was tough because of the pandemic. Now that the pandemic policy has changed, why are you still arbitrarily setting up roadblocks to the village?”

“Orders from above. You have to register.”

“You’re probably the only village in the whole country that requires people to register with their I.D. to get in.”

The village cadre remained silent.

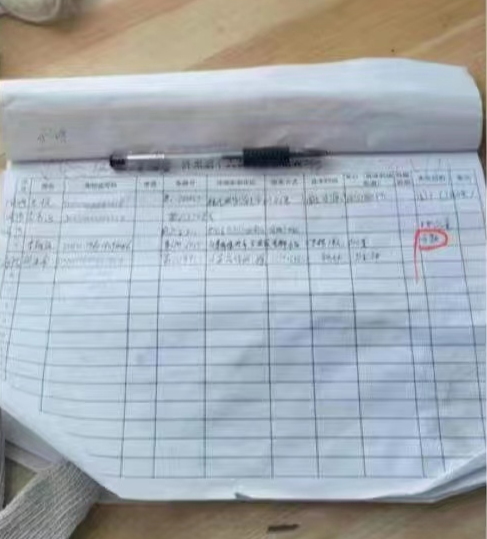

As he took our I.D. cards and started to register us, I craned my neck and glanced around. The A4-sized registration ledger was grease-stained, but it contained a wealth of content about previous visitors: full names, identity card numbers, and “purpose of visit.” There were also notations marking some visitors as “suspicious.” “Suspicious” in what sense, I wondered. It probably meant people like us.

ALT text: A tattered ledger shows columns listing dates, purpose of visit, names, I.D. card numbers, and other personal information about visitors to the village.

After registering, we asked if we could enter the village, but we were once again denied permission.

“Didn’t you just say that we could enter after registering?”

“We have to wait for permission from our boss.”

“So if your boss doesn’t give permission, we can’t go in?”

“That’s right.”

“We’re just here out of sympathy for that shackled woman’s eight children. All we want is to check how they’re doing, and then we’ll leave.”

“Let’s see if you get permission first.”

“If something similar had happened to your family, we’d be just as sympathetic. We’d want to pay you a visit, too.”

The village cadre kept his head bowed and said nothing.

Just then, a white car drove up, and two village cadres went out to intercept it and speak to the driver.

“Why are you here?”

“I’m going to my father-in-law’s house.”

“What’s your father-in-law’s name?”

“Dong …”

I stepped forward and asked, “He’s not even allowed to go to his own father-in-law’s house?”

“Mind your own business!” Apparently the village cadre thought I was being too nosy.

Another village cadre was on the phone, reporting on our situation: “Beijing license plates … two people … I heard there are more vehicles on the way …”

Not long after that, a group of auxiliary police officers showed up riding electric motorcycles.

We kept asking if we could go into the village, explaining over and over again that all we wanted to do was pay a brief visit to those eight children, but our requests were denied.

Seeing that it was approaching noon, and realizing that the situation was futile, we decided to drive back to Feng County.

But when we started our engine, we discovered that a white sedan had stopped in the middle of the road, blocking our retreat.

“You won’t let us go into the village to visit the kids, but you won’t let us leave, either. You’re unlawfully restricting our freedom of movement!” We protested loudly. “That’s a crime!”

One of the village cadres stood directly in front of our car. “Go ahead and leave,” he said tauntingly, “We’re not stopping you.” I pushed him out of the way and signaled to the driver to get ready to speed away. Suddenly, we found ourselves surrounded by a large group of men.

I promptly dialed 110 to call the police. A quarter of an hour later, the police still hadn’t shown up.

Later, I noticed a poster on the outside of the guardhouse, advertising a hotline number for the [non-emergency] community police service. I called the number, but there was no answer, and no one had showed up yet in response to my 110 call.

I dialed 110 a second time.

“There’s been a physical altercation at the entrance to Dongji Village. Why is it taking the police so long to respond?”

“The police station has already been notified, and they’ll arrive as soon as they can.”

“And how soon is that?”

……

About half an hour after my initial call, the first police car arrived.

The police started by asking for our full names and I.D. card numbers, and then asked where we’d come from and what we were doing here.

We answered each of their questions in turn, and reiterated that we had only come here to visit those eight children and offer them our best wishes for Lunar New Year.

“Have you been authorized to visit?” asked the police officer.

“Does a citizen need authorization to show their concern for another citizen?”

The policeman said nothing.

I pointed to the large group of men surrounding us. They were illegally restricting our freedom of movement by not allowing us into the village and not allowing us to leave. I also pointed to the white sedan stopped in the middle of the road, blocking our retreat.

“Wait a moment, just wait a moment,” said the policeman, “and someone will be here to explain.”

“We don’t need anyone to explain. You’re the police, and this is a case of public security. Are you saying there’s someone else capable of intervening in and obstructing police business?”

As we were arguing, a second police car arrived, and a man who looked like a higher-ranking local cadre got out. Once again, we were asked where we’d come from, where we were going, and what we were doing.

“We’ve come from Beijing to visit the shackled woman and her eight children. With Lunar New Year coming up, a lot of people have asked us to visit and offer them some support.”

“Well, in that case, you’ll need to report to the county Party committee propaganda department.”

“We’re private citizens, here on our own initiative. We’re not from the People’s Daily or CCTV or someplace like that. Why should we report to them?”

“Because anyone who comes here needs to report to them!”

We continued arguing, to no avail.

“All right, then we’ll go to the county Party committee. Can we go there now?” I asked the policeman.

“Yes.”

“But their car is still blocking us.”

“Whose car is this?” shouted the police officer. “Whose car? Move it!”

That village cadre took his sweet time climbing into the car and driving away.

At noon, with nothing to show for our visit, we left.

The fate of the shackled woman and her eight children will continue to haunt me. [Chinese]

The CDT Chinese site features a detailed archive of content related to the Xuzhou woman’s case, arranged both chronologically and by topic (users can toggle between the two arrangements).