A solitary protestor hung two banners calling for Xi Jinping to be removed from office and exhorting the populace to “Be citizens, not slaves,” an extremely rare act of overt political defiance on the eve of the 20th Party Congress. The unknown protester hung the banners from busy Sitong Bridge in Beijing’s northwestern Haidian district and lit a fire in an apparent bid to draw attention. Police later removed the banners. The red and white hand-lettered banner at left read: “We want food, not COVID tests; reform, not Cultural Revolution. We want freedom, not lockdowns; elections, not rulers. We want dignity, not lies. Be citizens, not slaves.” The banner at right read: “Boycott classes. Boycott work. Depose the traitorous despot Xi Jinping.”

CDT Chinese published two video compilations showing the incident from a number of different angles:

At The Wall Street Journal, Yoko Kubota, Jonathan Cheng, and Joyu Wang reported from Haidian in the aftermath of the one-man protest:

One man told Wall Street Journal reporters he saw the thick smoke and the unfurled banners hanging from the bridge at about 1 p.m. local time. Police arrived shortly after he saw the smoke, he said.

[…] Along one strip of stores, a police officer went door to door speaking to shopkeepers, while a number of police vehicles were stationed at each corner. Police officers directed traffic flow, which was otherwise normal for a Thursday afternoon. The overpass appeared to have been cleaned up.

[…] “#Haidian# tiny spark,” one Weibo user wrote in the short window of time before censors closed in, alluding to a revolutionary saying made famous by Mao Zedong: “A tiny spark can set the prairie ablaze.” [Source]

The protest ignited Weibo with commentary on the bravery of the protestor. CDT Chinese compiled dozens of comments, a selection of which are translated below:

@潮Su:O brave one, I salute you! 2022.10.13@棒崽的不寂寞星球·3·:Don’t be silent, speak up. Don’t be a servant, be a brave person.

@田纳西费曼:Courage is humanity’s most precious quality. I hope the brave one stays safe.

@矛盾體_CRAIGJOJO:When we hear about a brave person, it evokes feelings that are more complex than simple admiration or emotion. Are we mere bystanders? Do we have a connection to this person? Do we have the right to appraise them—even if our appraisal is well-intentioned? And yes, it’s quite possible that among that mix of emotions, we may feel a bit ashamed of ourselves. But no matter what, and at the very least, I hope to never lose that sense of shame.

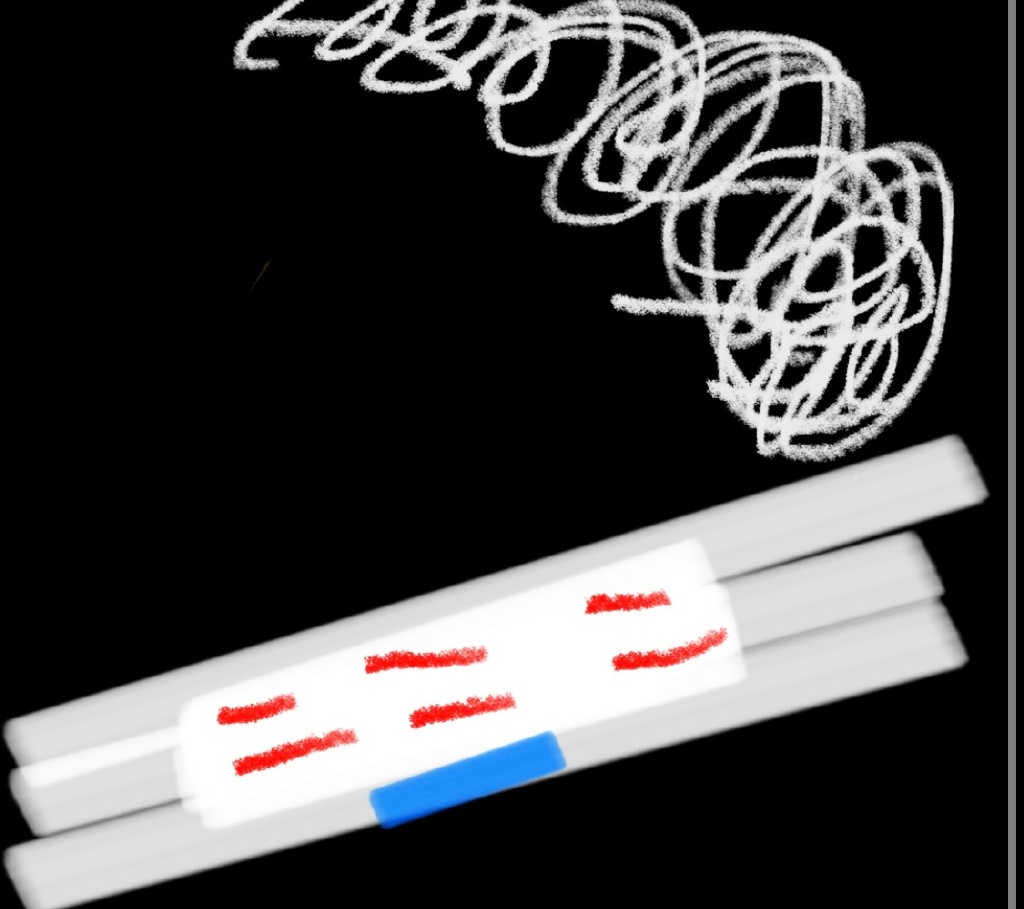

An abstract rendering of the banners hanging from Sitong Bridge, and the smoke rising from the fire.

@那先这样下次我买单:Brave one, we don’t deserve you.

@ManholeCover_:You may strike fast, but you can’t kill every brave person.

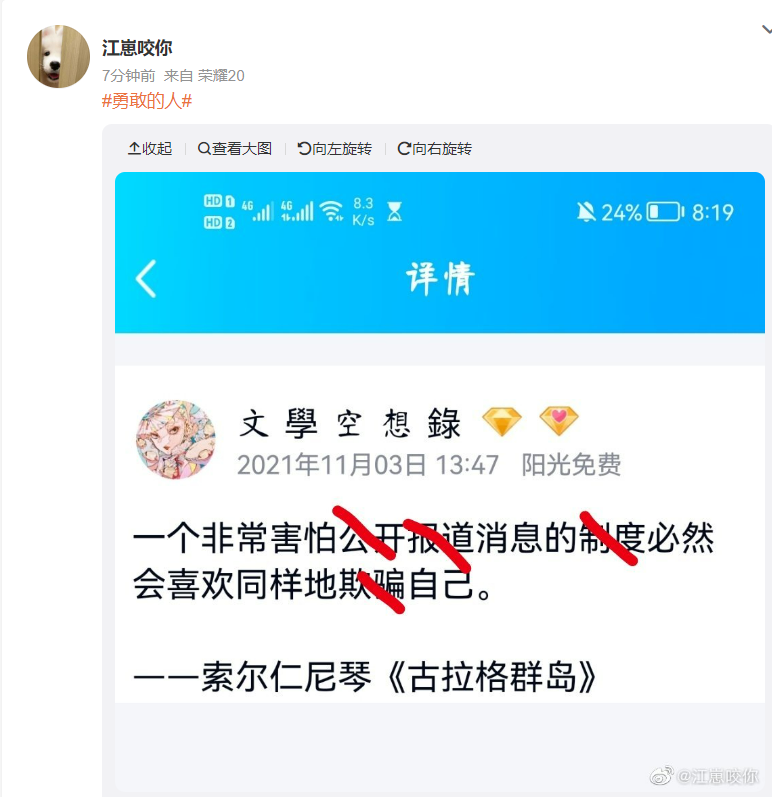

@江崽咬你:#BraveOne#

A screenshot shows a purported quote from Solzhenitsyn’s “The Gulag Archipelago”: “A system that fears open public reporting inevitably tends to deceive itself in much the same way.”

@thelastanimagus:I hope you are free, brave one.

@抹茶半糖加冰:So this country does have some brave people after all.

@Nov肆零肆:Respect. I hope he’s safe. [Chinese]

“That Moment”

This, then, is the meaning of your life—

one extraordinary leaf plucked from a forest,

a drop of water in a frying pan

transformed into that moment of billowing smoke.You’d had enough, so night became a torch—

you displayed your true self,

an individual trapped in a nonsensical world

transformed into that moment of nothing-to-lose.This, then, is the meaning of your disappearance—

one solid brick prised from a city wall,

a basin of cool water sprinkled into a volcano

transformed into the first note of a thunderstorm. [Chinese]

A vast array of terms, some only tangentially related to the protest, were censored in its aftermath. On Weibo, searches for “brave,” “the brave one,” “bridge,” “salute,” “Haidian,” and “hero” only returned results from government-affiliated accounts, or “Blue V’s,” indicating intense censorship. Weibo also banned the hashtag #Beijing. Douyin, TikTok’s Chinese sister app, restricted search results for “Beijing” to government affiliated accounts. Searches for “Sitong Bridge” returned next to no results across Weibo, Zhihu, Douban, and Baidu. In at least one case, sharing an image of the protest in a WeChat group led to a 24-hour ban from the platform’s group chat and Moments features. QQ Music deleted all comments under the song “The Brave One” by No Party For Cao Dong. Apple Music removed the song “Sitong Bridge” from its Chinese streaming service and Baidu removed a page on the song from its digital encyclopedia. CDT’s Eric Liu, a former censor, pointed out that the intensity of this round of censorship rivaled, if not surpassed, the bout that followed Peng Shuai’s accusation that former Politburo Standing Committee member Zhang Gaoli sexually assaulted her.

weibo said the statement "I saw it" "violated rules and regulations" and suspended the user for 60 days

we've reached the point where both "I saw it" and "I didn't see anything" could be illegal https://t.co/8slC2kQvat— Chenchen Zhang 🤦🏻♀️ (@chenchenzh) October 13, 2022

In contrast:

A search of Shenzhen: 12399106 results

A search of Guangzhou: 13241229 results

A search of Shanghai: 38868221 results— Kerry Allen 凯丽 (@kerrya11en) October 13, 2022

The stringent censorship of posts related to the Beijing bridge incident is in line with a broader intensification of censorship in the lead-up to the 20th Party Congress. Even innocuous commentary is now subject to erasure. Now-deleted examples include a post predicting an upcoming rainstorm; a gif of a person mopping the ocean, with the caption “idiocy with no end in sight”; and smiley-face and bear emojis. In the latter case, a group of students were attempting to avoid censorship of the word “bust size,” and used the bear emoji as a homophonous stand-in for breasts—unaware that it could be construed as an insult for Xi Jinping. (This is not unprecedented. Earlier this year students who thought they had happened upon a WeChat “bug” were, in fact, using an obscure insult for Xi that triggered automatic censorship.)

Weibo began censoring search results for the term “One Press, Three Functions,” a Bilibili feature that allows users to like and save a video while tipping the creator, because it is roughly homophonous with, “Presto, three consecutive terms,” an oblique reference to Xi Jinping’s all-but-guaranteed upcoming third term in office. Douban censored pages related to the Japanese manga “Death Note”, perhaps due to fear that netizens were using the central conceit of the story, that whoever’s name is written in the eponymous notebook will die, to discuss Xi. One commenter asked: “How did Douban know I write his name in my heart’s ‘Death Note’ every day?”

Mentioning Xi in posts to foreign social media can also be dangerous for Chinese internet users. Twitter user @MianMaoKu posted a thread alleging local police and plainclothes officers came to her house near midnight, brought her to a local police station, and demanded she delete tweets regarding “THE leader” and forced her to sign a promise to “try not to post anything sensitive regarding the national leader.”

The rise in censorship has been accompanied by a crackdown on the tools used to skirt the Great Firewall. Great Firewall Report, an organization that monitors censorship in China, found that China has blocked servers that host protocols employing transport layer security (TLS) to avoid censorship. GFW Report told The South China Morning Post, “This new blocking coincides with the most politically sensitive weeks in China.” A study published in the academic journal PNAS found that downloads of VPNs—tools often used to circumvent internet controls—and searches for sensitive content jumped during lockdowns, as did Twitter use. New Twitter users followed Chinese citizen journalists, foreign media, and activists in droves, an indication that demand for uncensored knowledge increases during crises.

Poem translated by Cindy Carter.

source https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2022/10/beijing-bridge-protest-scraped-from-web-as-censorship-tightens-before-party-congress/

No comments:

Post a Comment