Tuesday, 30 August 2022

Media Forums Promote Journalist Collaboration and Position Chinese Narratives in African News Agencies

This month, China hosted two major media forums aimed at promoting synergy between Chinese and foreign media organizations. Both forums highlighted the importance of training programs for journalists in the Global South. These forums also signal the growing reach of Chinese state media narratives in African participants’ respective coverage of China.

The first event was the 5th Forum on China-Africa Media Cooperation, co-hosted by China’s National Radio and Television Administration, the Beijing municipal government, and the African Union of Broadcasting (AUB). The gathering, held last Thursday and Friday in Beijing, brought together over 240 delegates from 140 countries to celebrate the forum’s ten-year anniversary. Xi Jinping sent a congratulatory letter urging the media from both sides to tell better stories about China-Africa cooperation. PR Newswire summarized the contents of the forum, including sessions on “content cooperation” and “digital convergence”:

Themed “New Vision, New Development, and New Cooperation,” the Forum held sessions on media development policy, content cooperation and innovation as well as new technology application, and digital convergence.

The Forum published a joint declaration that reviewed the decade of achievements of China-Africa media cooperation. In mapping the prospects and plans for future media development, it proposed five initiatives, including deepening cooperation and communication, supporting global development, telling stories of China-Africa friendship, promoting digital media development, and strengthening youth exchanges.

In addition, the Forum featured events such as the first broadcast exhibition of African programs in China and a short video collection on the topic of “my story of China-Africa friendship.” It also published 12 cooperative achievements in terms of program co-broadcasting, documentary creation, program innovation, and new media cooperation. [Source]

One prominent theme of this media collaboration is supporting Chinese training programs for African journalists. Referencing these at a follow-up meeting to the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) the week prior, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said he supported media organizations “in enhancing exchange and cooperation to deepen friendship between the Chinese and African peoples.” At last week’s forum, AUB CEO Grégoire Ndjaka praised China’s training programs, which “[intend] to expose African journalists to Chinese culture and lifestyle” and regularly send scores of groups of African journalists to China each year. Speaking at the forum on behalf of the 40 African journalists currently participating in one such program in China, a journalist from the state-run Somali National News Agency (SONNA) described his experience:

“I was here in Beijing for the 2019 Media Exchange Program together with other 33 fellow African brothers and sisters mostly from public media institutions and I do recall all events I attended, visits and tours made and what impressed us during our stay in China at the time”, he stated.

“We visited ten provinces in China such as Hainan, Xi’an, Shanxi, Hunan, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Shaanxi, Hubei and Zhejiang and Shanghai. We saw amazing and tangible achievements made and on-going development projects throughout the provinces. Advanced technology in place, high speed trains and better infrastructure impressed us during our exploration for the ten months’ period”, he recounted.

[…] Notably, these journalists covered their governments’ support for Beijing’s ‘One China’ policy and expressed solidarity during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2019 [as] well. [Source]

As it turns out, SONNA runs a substantial amount of pro-CCP news content. On Sunday, it published an article describing praise for the Chinese government’s policies in Xinjiang from an official of the Somali embassy in Beijing, who was interviewed by “a visiting journalist from [SONNA],” likely the same individual who spoke at the forum two days prior. Another SONNA article on August 10, penned by the Chinese ambassador to Somalia, praised China’s Global Security Initiative. On August 4, SONNA published an article without a byline that expressed firm support for China’s claims of sovereignty over Taiwan. The piece was, in fact, a lightly edited version of an article that would appear a day later on the website of the Chinese embassy in Somalia, explicitly credited to the ambassador. That same day, SONNA ran another article from Xinhua. Only two other articles about China were published by SONNA in August.

Earlier this month in Xi’an, the People’s Daily and the provincial government of Shaanxi hosted the 2022 Media Cooperation Forum on Belt and Road, drawing over 120 media representatives from over 40 countries and international organizations. Huang Kunming, head of the Publicity Department of the CCP Central Committee, urged participants to highlight their nations’ joint BRI efforts, stating that media exchanges and cooperation are essential to building the BRI. The Global Times noted that the forum’s push for media cooperation was an attempt to “battle hegemony” by the West, and cited the vice president of Ethiopia’s state-run Ethiopian News Agency (ENA), present at the forum, who also urged greater cooperation.

ENA has heeded Huang’s call by covering China favorably and praising China-Africa media exchanges. One of its journalists, currently participating in a Chinese media training program, published an article in ENA this month praising China’s cooperation with Ethiopia, using language such as: “The Chinese approach toward Africa […] involves upholding friendship and equality.” On Sunday, ENA published an article relaying a call by the Ethiopian ambassador to China to “further enhance and strengthen our [media] collaboration through co-production of programs,” specifically those regarding news coverage, content creation, channel building, staff training, and other exchanges. All eight of the articles about China in ENA this month praise China-Ethiopia cooperation: affirming China’s Taiwan policy, praising Chinese projects in Ethiopia and Africa, and parroting Chinese embassy press releases.

Reshaping narratives is an explicit motivation for China-Africa journalist exchanges. A CGTN op-ed published on Sunday argued that media plays an important role in “shaping the right discourse” about China-Africa cooperation, and that “[e]nhancing in-depth media exchanges between the two sides can also assist in fact checking and debunking myths.” Another recent op-ed in China Daily argued that China-Africa media collaboration can help “fight post-truth narratives” wielded by “anti-China critics.” In a report published this month by the Atlantic Council, Kenton Thibaut explained that a primary way that the Chinese government advances its global discourse power in the digital realm is by leveraging media platforms to shape local information environments by spreading pro-China propaganda:

China’s view of the utility and timeliness of this approach is spelled out plainly in an April 2021 guiding policy document released by the [Central Propaganda Department] on shoring up China’s “external public opinion work.” The document stated that “the rapid development of the internet has accelerated the process of networkization and digitization of the international mainstream media. The internet is reshaping the international public opinion pattern and the international media ecology and has increasingly become an important battlefield for major powers to compete for discourse power.

[…] In a document examining China’s external propaganda activities released in June 2021, the [Central Propaganda Department] praised the strides China has made with international media in recent years, stating, “relevant key foreign propaganda media have made great strides to go overseas, deeply implemented localization strategies […] from topic selection to language and style, external reports are closer to overseas audiences, and the originality, speed, view count, and citation rate of news reports have greatly increased. [Source]

Such leverage comes partly from Chinese training programs of African journalists and the pro-CCP narratives they publish in their respective outlets. Zambian media scholar Gregory Gondwe analyzed this leverage in a July 2022 academic paper that compared the impact of Chinese, American, and British short-term training programs on African journalists. His findings revealed that while American and British programs exhibited comparably less direct ideological influence on their participants, Chinese programs attempted to directly control journalistic autonomy and incentivize positive reporting about China:

China’s media expansion to Africa provides a unique phenomenon to the African media and its journalists. As noted in the findings, China’s journalism training programs were encapsulated by open and direct control of journalistic autonomy, and subsequently cultural and institutional autonomy. Most respondents indicated that the Chinese training programs were all about orienting African journalists to the Chinese culture – and especially with the statement, “this is how China looks”. By so doing, African journalists were expected to report China in a way that China considered accurate – that is why there were follow-ups throughout the publication process. An incentive meant that a journalist had the standards and should continue reporting in the way China wants. [Source]

source https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2022/08/media-forums-promote-journalist-collaboration-and-position-chinese-narratives-in-african-news-agencies/

Saturday, 27 August 2022

Cadres Instructed To Buy, Buy, Buy China Out of Property Crisis

Are cadres the answer to China’s property market crunch? Some local officials seem to believe so. Hundreds of thousands of homebuyers across China have boycotted their mortgages payments in protest against the stalled construction of their homes, with some referring to themselves as “Camel Xiangzi,” the ill-fated protagonist of a 1937 satirical novel by Lao She. The roots of the crisis are complicated but can be broadly explained by a 2020 crackdown on excessive borrowing by developers and risky debt financing fueled by misplaced optimism about ever-rising home prices. While the Politburo has enjoined that stalled residential construction projects be finished in a timely matter (and thus mortgage payments resumed), some localities have taken stabilization to a new extreme: compelling low-level cadres to purchase homes, regardless of how many they already own. The party secretary of Hunan’s Shimen County instructed local officials: “I hope that every cadre present at today’s session can take the lead in purchasing homes. If you’ve already bought one, buy two. If you’ve already bought two, buy three. If you’ve already bought three, buy four.”

Public reaction was a mix of jokes at the cadres’ expense, concern about whether the order might lead to increased corruption, and facetious solutions:

@holyhello:A red health code to all who don’t buy.

@MR尚人:But first let’s have an accounting of where they’re getting the money to buy all these houses.

@会落泪的东海鲨鱼:The leaders are panicking because nobody is buying houses. They’re hurting because the value of their own homes has dropped.

@凌晨昨迟人:Turn all vacant houses into quarantine facilties. Give everyone who doesn’t own a home a red code. Put everyone with a red code in the newly designated quarantine facilities—all at their own expense. [Chinese]

An unverified but widely circulated photograph of another government meeting in an unknown location suggested that home purchases had become part of cadre performance evaluations:

完不成卖房任务就会被调岗,今后还要把是否在新城区购买商品住宅作为干部提拔任用的考核内容。 pic.twitter.com/cNfmUc18Ol

— 曹山石 (@caoshanshi) August 14, 2022

Observers noticed that the injunction to buy homes with no regard for need seemed to violate Xi Jinping’s instruction that “houses are built to be inhabited, not for speculation,” made during his keynote address at the 19th Party Congress in 2017 and oft repeated by other officials since then. In a WeChat post on the blog @观人随笔, archived by CDT Chinese, the author called into question the political, ethical, and practical implications of the push to have cadres buy more homes:

First, doesn’t calling for home purchases in this manner deviate from the Center’s repeatedly emphasized principle that “housing is for living in, not speculation”?

[…] Second, are all of these comrades and leaders renting? If they already have their own homes, why call for them to purchase more?

[…] Third, what does a family need with four houses? If it’s a family of four, I suppose one person could live in each house. But what if they’ve fewer people than that?

[…] Fourth, if purchasing houses is no longer correlated to any real need but rather to an effort to eliminate excess housing inventory or to “rescue” any one particular group or sector, does that make any sense? Is it appropriate?

[…] Fifth, hasn’t the goal of developing our real estate sector always been to meet the housing needs of everyone in society, and to rein in affluent homeowners so they don’t crowd out less affluent aspiring homeowners? [Chinese]

Censors have cracked down on sharper criticism, including one WeChat essayist’s satirical endorsement of the policy. CDT Chinese archived the post by @老干体v in which the author argued that by drastically increasing the hiring of new cadres, governments could kill two birds with one stone, tackling both youth unemployment and the property market crisis:

Leaders’ demands that cadres buy homes are not completely absurd. For employees in the private sector, simply making a living has been no small achievement over these three pandemic years. Yet I fear that big purchases, like a home, are beyond their reach in the short term.

Yet public-sector employees easily make double their salaries in places like Qinghai, and at the very least half as much again, as in Henan.

A chart comparing cadre salaries with private sector salaries across provinces.In our country, where cadres are decidedly middle-class, not to mention their traditional role as models for public behavior, how could they not put themselves on the front line of the crisis we are facing?

[…] As I see it, we should embark on large scale recruitment to rescue both the real estate sector and local government finances. After all, there are many college graduates hoping to serve the people: “2,000,000 took the civil service exam and 9,000,000 took the teachers’ exam—what’s up with this generation?”

We could solve the unemployment problem and rescue local government finances, the best of both worlds.

Yulin City in Guangxi is a great example of how to do this:

Yulin City, Guangxi: Municipal public health departments health commissions are giving hiring preferences to qualified recent graduates who have purchased new homes in Yulin City.

Selling civil service jobs, haha. [Chinese]

One WeChat essaysist joked that corrupt cadres purchasing houses was good for the economy, or at least better than squirreling away ill-gotten cash in their homes and waiting for investigators from the Central Commission for Discipline Investigation to discover it. Many though not all such intimations that the cadre home-buying scheme is a simple form of public corruption were taken offline. One essay used a meme template from the hit Chinese Western Let the Bullets Fly, in which a gangster takes over the administration of a small town in 1920s Sichuan in hopes of striking it rich, to joke that current leaders hoping to earn a fortune through real estate had missed their chance. That essay was removed from WeChat, although it was unclear if it was the work of censors or the author’s own choice:

We’ve arrived too late. The past couple of Goosetown county magistrates have already collected advance taxes for the next 90 years. [Chinese]

The half-baked cadre property-purchasing scheme seems to have done little to revive national property markets. The mortgage boycotts and slowdown in new sales have left some developers unable to pay their debts. Earlier this week, China lowered its loan prime rate, a move that allows for cheaper mortgages but is unlikely to solve the crisis. “So far, lower mortgage rates haven’t translated into higher property sales due to the lack of confidence in large developers and the presales model,” Invesco global market strategist David Chao told The Financial Times. In his Carnegie Endowment for International Peace blog, Michael Pettis gave an overview of the crisis and offered his prediction as to what happens next:

Under these conditions, it is hard to predict what will happen over the short term. My best guess is that because of the Chinese Communist Party’s upcoming National Congress, Chinese regulators will prioritize stability over all other things. Any additional outbreaks within the financial system will quickly be absorbed by local government borrowing and the bigger banks. Once the pandemic lockdowns end, the regulators may even unleash a series of “bazooka-like” policies to try to reverse [investor?] sentiments, kick-start rising property prices, and boost confidence among creditors and depositors.

But even if this works temporarily, it cannot go on forever. At some point, Beijing must take concrete steps to allocate the costs of rising insolvency, most likely to local governments, although this will not be easy. If it doesn’t do so, eventually the debt levels will become unsustainable and, perhaps with an evaporation of credibility, the system will force its own allocation of costs.

The latter scenario is usually referred to as a debt crisis, and while I think a debt crisis in China is still very unlikely, this is because I think Beijing still has the ability to restructure liabilities. But one way or another, losses must (and will) be forced onto some sector of the economy, either explicitly as a political decision or implicitly as the economy adjusts to allocate the losses to those sectors least able to protect themselves. [Source]

source https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2022/08/cadres-instructed-to-buy-buy-buy-china-out-of-property-crisis/

Friday, 26 August 2022

Four Men in Jiangxi Punished for Breaking COVID Rules With “Malicious Mourning”

Police in Yingtan, Jiangxi province, have become the object of derision online after announcing that they had punished four men for evading a pandemic lockdown to attend the funeral of an elderly family member. The phrase used in the announcement—”malicious mourning” (恶意奔丧, èyì bēnsāng)—calls to mind the many other previously innocuous activities that have been dubbed “malicious,” or even criminalized, under China’s stringent zero-COVID policies.

Caixin’s Li Hang reported on the background to the funeral story and the ensuing social media backlash, noting that the “hashtag #Local authorities respond to an incident in which four men were punished for violating control measures to attend a funeral #官方回应违反防疫规定参加葬礼被罚 has been viewed over 70 million times, receiving over 25,000 comments on […] Weibo”:

The men at the center of the case were caught on their return home from the funeral of one of the men’s father-in-law. One of the men, named Yu, left his residential community in Yingtan city, Jiangxi province, on the grounds of buying vegetables on Aug. 17.

Yingtan put three districts under three-day lockdown on Aug. 14, including one district where Yu lives. Most residents there were barred from leaving home except for allowing a single member of the household to buy groceries once every two days.

On Monday, when the four men returned to Yu’s residential community, they were stopped by security guards at the community gate who called the police about their supposed infraction, a since-deleted announcement by Yingtan authorities said on Tuesday.

After arriving at the scene, the police slapped the men with administrative penalties and transferred them to centralized quarantine, according to the announcement. Administrative penalties entail a fine or detention. [Source]

An article from self-published media outlet 陆火Media, archived by CDT Chinese editors and partially translated below, described the public shock over the absurdity of police announcements about this case of “malicious mourning”:

Since the advent of Omicron, […] there has been a series of bizarre incidents such as “malicious homecomings,” “malicious meals,” “malicious doctor’s visits,” “malicious labor,” and even “malicious cucumber-selling.”

On August 23, the Xinjiang district substation of the Public Security Bureau of Yingtan city, Jiangxi province, reported an equally bizarre incident of “malicious mourning.”

[…] Some netizens pointed out that while shopping for groceries was a valid excuse for leaving the house [during a pandemic lockdown], attending a funeral was not. How inflexible must pandemic prevention policy be, that it would drive a group of ordinary people to lie, take elaborate detours, and even wade across a river to get to a funeral?

Other netizens pointed out that attending the funeral of an elderly family member is both a valid excuse and an extenuating circumstance. Furthermore, all four men had green health codes and had taken nucleic-acid tests within the previous 24 hours, and did not spread the virus to anyone. Shouldn’t the police have just given them a stern talking-to, rather than insisting on administrative penalties?

[…] On August 21, the Xinjiang district PSB substation issued an announcement under the title: “Say NO to Violations of Pandemic Prevention Law: 300 People Punished for Violating Pandemic Prevention and Control Regulations!”

[…] Among the reasons given for these punishments were “gathering with other people in violation of regulations,” “opening for business in violation of regulations,” “entering and leaving the neighborhood in violation of regulations,” “doing construction work in violation of regulations,” “operating a street stall in violation of regulations,” “going out for morning calisthenics in violation of regulations,” “going fishing in violation of regulations,” and more. [Chinese]

Previous iterations of so-called malicious activities include “malicious homecomings,” the subject of a January 2022 viral video clip in which Dong Hong, a county magistrate from Dancheng in Henan province, warned that residents returning to his county from medium and high COVID risk areas would be subject to quarantine followed by immediate arrest, even if they could show a vaccination certificate or proof of a negative nucleic-acid COVID test taken within the previous 48 hours. Various online activities have also been branded as malicious, a situation summed up in this humorous netizen comment from March 2022: “Malicious screenshots, malicious compilation, malicious satire. Malicious exposure of past humiliations, malicious Weibo posting. No screenshots! No compilation! No satire! No exposing past humiliations! No Weibo posting! No malice at all!!! No breathing! No resistance!”

source https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2022/08/four-men-in-jiangxi-punished-for-breaking-covid-rules-with-malicious-mourning/

Thursday, 25 August 2022

Record Heat in Central China Causes Power Shortages, Economic Strain, and Suffering

A massive, months-long heat wave has scorched regions in central China. Intense droughts and evaporating water sources have choked energy supplies in several regions reliant upon hydropower, causing widespread power cuts and forcing businesses of all sizes to halt operations. Human suffering has accompanied the economic strain, with many netizens testifying to fatalities in their communities. As China grapples with interminable pandemic lockdowns, rising geopolitical tensions, and economic slowdowns, global climate change has reasserted itself as an existential issue that is too hot to ignore. David Stanway from Reuters reported on the intensity of this recent heatwave:

China’s heatwave, stretching past 70 days, is its longest and most widespread on record, with around 30% of the 600 weather stations along the Yangtze recording their highest temperatures ever by last Friday.

[…] China’s National Meteorological Centre downgraded its national heat warning to “orange” on Wednesday after 12 consecutive days of “red alerts”, but temperatures are still expected to exceed 40 Celsius (104 Fahrenheit) in Chongqing, Sichuan and other parts of the Yangtze basin.

One weather station in Sichuan recorded a temperature of 43.9C [111 Fahrenheit] on Wednesday, the highest ever in the province, official forecasters said on their Weibo channel. [Source]

China is experiencing the worst heatwave ever recorded in global history.

The combined intensity, duration, scale, and impact of this heatwave is unlike anything humans have ever recorded.

Over 260 locations have seen their hottest days ever during this 70+ day heatwave. pic.twitter.com/TCKvR37Em3

— Colin McCarthy (@US_Stormwatch) August 23, 2022

Unimaginable heat in China 🇨🇳

The longevity and intensity of the heatwave is hard to comprehend. Too many heat records to count, both day and night.

Beibei hit 45°C for two consecutive and some places not falling below 34°C at night.

The heat is ongoing… pic.twitter.com/pxWgaMDZQ0

— Scott Duncan (@ScottDuncanWX) August 20, 2022

The heatwave has caused widespread droughts. China’s National Meteorological Center stated that parts of Jiangsu, Anhui, Henan, Hubei, Zhejiang, Fujian, Jiangxi, Hunan, Guizhou, Chongqing, Sichuan, Shaanxi, Gansu and Tibet have all experienced moderate to severe droughts. Jiangxi’s Poyang Lake, China’s largest freshwater lake, was reduced to 25 percent of its usual size. Rainfall in the Yangtze River basin has been about 45 percent lower than normal since July, and water levels dropped so low that previously submerged 600-year-old Buddhist statues were uncovered in the river.

Shocking image of Chongqing river shared by Dutch CG on LinkedIn this morning.

CQ is massive industrial base, but like neighboring Sichuan province, forced to shut down factories for up to a week to conserve water.

Is 2022 the year climate change becomes tangible in China? pic.twitter.com/q1cjJlEyIp

— Richard Brubaker (@richbrubaker) August 21, 2022

Officials have sprung into action to mitigate the drought’s impact on the country’s autumn harvest, which accounts for 75 percent of China’s total grain supply. China’s Minister of Agriculture and Rural Affairs declared an “all-out battle” against drought, and four government departments issued an urgent joint emergency notice urging local authorities to ensure “every unit of water … be used carefully.” The government has begun using cloud seeding, forcing rain by firing chemicals into the sky, and discharged hundreds of cubic meters of water from reservoirs to replenish rivers in agricultural zones. Noel Celis from AFP reported on other government measures to protect the harvest:

China produces more than 95 percent of the rice, wheat and maize it consumes, but a reduced harvest could mean increased demand for imports in the world’s most populous country — putting further pressure on global supplies already strained by the conflict in Ukraine.

State media reported Wednesday evening that the government had pledged 10 billion yuan ($1.45 billion) to help ensure good rice harvests this autumn.

A meeting of Beijing’s State Council, presided over by Premier Li Keqiang, had agreed the government should “do an even better job in fighting and reducing drought”, broadcaster CCTV said.

Officials also called for “a combination of measures to increase water sources to fight drought, first ensure drinking water for the people, ensure water for agricultural irrigation, and guide farmers to fight drought and protect autumn grain”, it added. [Source]

In provinces such as Chongqing and Sichuan, which are heavily reliant on hydropower, energy resources have been stretched thin. CK Tan from Nikkei Asia reported that due to hot temperatures and low water supplies, local governments have ordered power cuts in order to save electricity:

Last week, the temperature soared to 45 C in Chongqing city, where some residents scrambled to find cooler refuge in subway stations and supermarkets.

On Monday, the city ordered that opening hours at hundreds of shopping malls be shortened from 4 p.m. to 9 p.m. to “ensure the safe and orderly supply of power and guarantee the people’s basic needs,” the local government said.

Sichuan had ordered companies using industrial power to suspend production for six days starting Aug. 15. Local media report that businesses have been told to extend that suspension. The policy applies to 16,000 companies in 19 cities across the province, including a Toyota Motor factory and production facilities for key Apple supplier Foxconn.

Meanwhile, Huzhou City in Zhejiang Province, an industrial hub near Shanghai, advised residents to keep air conditioning at certain levels, while tenants living on the first three floors of high-rise buildings were asked to use stairs instead of elevators. [Source]

Shanghai's major landmarks are set to go dark on Monday and Tuesday to save electricity, as several cities face rising energy demand amid insanely hot temperatures. pic.twitter.com/KkYeKKp27I

— Bibek Bhandari (@bibekbhandari) August 22, 2022

Manya Koetse from What’s On Weibo documented how local residents in Sichuan and Chongqing adapted to the heat wave and energy cuts:

[The power cuts] led to some extraordinary scenes from Sichuan and Chongqing subways, where travelers found themselves traveling in the dark or with only emergency lights on.

[…] Left without airconditioning, some offices also used big blocks of ice to keep employers cool.

[…] Some viral images showed residents sleeping in underground parking lots (#四川达州出现停电居民发声#).

[…] Another viral video from the city of Guang’an showed how a woman used a rope to get her order delivered to the 25th floor of her apartment building, where the elevators stopped working due to the power cuts (#高温停电女子拉绳吊外卖上25楼#). The woman had allegedly ordered in food at 4pm, expecting a power cut at 6pm, but then the elevators stopped running at 5pm already. [Source]

Some netizens found news of the heat wave and power cuts entertaining and mocked those affected by the heat using the viral hashtag #ThePeopleOfChongqingAndSichuanAreAboutToCry#. Censors also took down certain WeChat posts criticizing poor energy planning in Sichuan, and some news outlets sugarcoated the heatwave and toned down its human toll. In response, many netizens criticized the sanitized news coverage and provided first-person accounts of their struggles. Some called out instances of perceived energy waste, such as Shanghai’s decision to put on a light show for pop singer Yan Haoxiang while subway stations in Sichuan had no lights. “The stinking rich are living it up, while people are dying of heatstroke on the street,” one netizen wrote on Weibo. CDT Chinese editors collected other netizen comments containing details of how people were impacted by the heat and criticism of apathy towards their suffering:

会拥有洋娃娃吗_:I’m speechless that anyone would find this amusing. At night, the emergency ward of Chengdu Hospital is packed with old people suffering from heatstroke. The ICU is full. Doctors are seriously telling relatives that their elderly family members could die at any moment. Why does the Internet still find this entertaining? I don’t understand.

重生之我是爆炒淀粉肠:It’s not that we’re not “about to cry,” we’re actually dying.

嘎嘎很尬:This hashtag waters down the suffering. Can’t they see how many people have died from heat exhaustion and heatstroke?

告诉花城我爱他nice:To the person who came up with this sort of hashtag: don’t you have a heart? Why don’t you come and find out what it’s like to spend a whole day in 40-degree heat during a power outage? I wonder how many people who survived the pandemic won’t survive this summer.

梨花:Forest fires are raging in Chongqing, old people aren’t going to survive this hot summer, hospital emergency wards have a constant stream of patients coming in with heatstroke, factories are closed, and businesses have limited their hours. Why would someone use the phrase “about to cry” to sum up these disasters? Is that hashtag even still on the hot search list? [Chinese]

The energy crunch has become a national issue, since numerous neighboring provinces source their electricity from hydropower from Sichuan and Chongqing. As a result of the energy supply bottleneck, governments are turning to coal to meet energy demands. Chen Xuewan, Fan Ruohong, and Denise Jia from Caixin reported on Sichuan’s renewed appetite for coal:

The situation is so dire, some have called for shuttered power plants fueled by coal– which accounted for 56% of total power consumption in 2021 – to be turned back on, while approvals for new plants have surged this year, seemingly flying in the face of the government’s policy to cut coal use as part of its goal to reach peak carbon emissions by 2030.

In fact, provincial governments approved plans to add 8.63 gigawatts of new coal power plants in the first quarter of 2022 alone, already 46.55% the capacity approved throughout 2021, according to a report published by Greenpeace East Asia’s Beijing office last month.

Even during the wet season that sees rains swell the Yangtze River, Sichuan needs to increase output at coal-fired power plants to meet not just its own energy needs, but also out-of-province demand, Sichuan Electric Power Trading Center said in a report early this year. [Source]

However, Zhao Ziwen from the South China Post reported that coal will not be enough to satisfy Sichuan’s energy needs, let alone those of other provinces:

[S]upport for coal-fired power plants alone will be “insufficient” to deal with Sichuan’s problem, because thermal power makes up a small part of its energy mix, said Lin Boqiang, dean of the China Institute for Studies in Energy Policy at Xiamen University.

The province relies on hydropower to generate around 80 per cent of its electricity, while thermal power generates less than 20 per cent, data from Sichuan Power Exchange Centre showed.

“Sichuan’s coal power does not account for a high proportion [of total power generation], transporting coal into the Sichuan can only ensure that coal-power equipment does not shut down,” said Yuan Jiahai, a professor at the School of Economics and Management at North China Electric Power University. [Source]

source https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2022/08/record-heat-in-central-china-causes-power-shortages-economic-strain-and-suffering/

Wednesday, 24 August 2022

Beijing Protest Art Reveals Frustration With Zero-COVID Policy

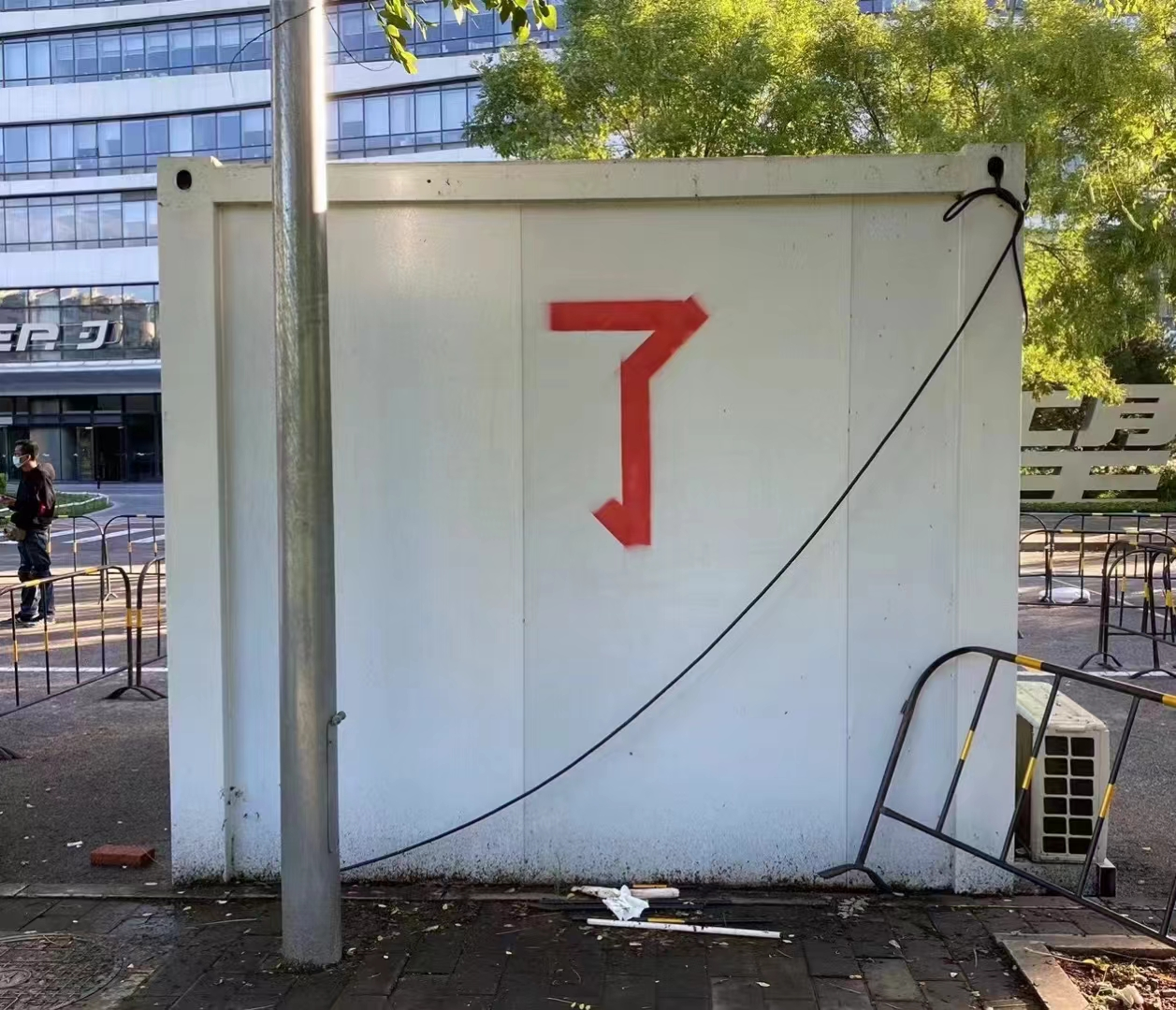

Protest art scrawled upon Beijing covid testing stations reveals an undercurrent of anger about China’s zero-COVID policy in the capital. The two seemingly unrelated protests are part of a larger stream of oft-censored artistic dissent against the country’s pandemic policy. Both protests turned testing booths, which have sprouted up everywhere in order to create “15-minute Testing Service Circles” in compliance with central government mandates, into a canvas. CDT Chinese archived photographs of the protests, both of which were hastily scrubbed off of the testing stations and censored from the internet. The first protest:

The first protest, graffiti scrawled on two separate testing booths in the same hand, referenced two defining phenomena in modern Chinese history: the 1989 Tiananmen democracy movement and the mass demolition campaigns of the 21st century that earned China the nickname, “where should we demolish?” The artist wrote, “give me liberty or give me death,” a translation of Patrick Henry’s famous 1775 demand that was later adopted by student protesters in 1989, some of whom repurposed it to “democracy or death.” The unknown protester also mimicked the once-ubiquitous “demolish” signs, the character chāi 拆 circled in red, that were seen across China. Mass demolitions left wide swathes of Beijing in rubble, thrusting thousands of people designated by the government as “low-end population” homeless. Perhaps less poetically, the protester also wrote “dumbass ‘prevention and control.’”

The second protest:

[Chinese]

The second protest involved single characters spray-painted onto eight covid testing booths across Beijing’s Wangjing District that, read together, spelled out: “It’s been three years, I’m already numb.” Since February 2020, when he chaired a 170,000 cadre conference on China’s pandemic policy, Xi has repeatedly stressed that cadres must “overcome paralysis, war-weariness, ‘get lucky’ mentality, and complacency,” most recently doing so during Shanghai’s lockdown. China’s ‘prevention and control’ policy has become a campaign that demands all-out mobilization, leaving no room for “numbness.” As of April, at least 4,000 officials had been punished for outbreaks in their districts—fear of that fate is a key pillar of the country’s COVID policy, writes Dali L. Yang of the University of Chicago.

The Beijing protests are by no means the first outbreaks of artistic dissent against zero-COVID. In November 2021, a Beijing Film Academy student wearing a face mask over their eyes locked themselves in a cage atop which a sign said, “don’t leave the cage unless strictly necessary,” in protest of the schools’ lockdown. Hashtags about the performance were censored on Weibo, as were posts discussing it on Zhihu. During the 2022 Shanghai lockdown, unknown protestors hung banners decrying both the policy itself and the censorship used to shield it from criticism. Tongji University students created ever more abstract depictions of a student’s angry message about the school’s censorship of student criticism of the lockdown measures: “Stop reading from your f***ing script. Why won’t you unmute me? You bastard.” One Shanghai rapper created a track titled “New Slave” that finished with the lines: “When the uniformed care only about their careers and don’t give a shit about life or dignity.” The song was swiftly banned on Weibo and the author later removed it from YouTube due to concerns about the video’s rapid spread. Most famously, the mini-documentary “Voices of April” went viral despite censors’ all-out efforts to quash it. Leaked directives from the Beijing and Guangdong Cyberspace Administrations directed that censors immediately begin a “comprehensive clean-up” and bar “without exception” the video and all derivative images.

China’s covid policy itself sometimes resembles performance art. Economist correspondent Don Weinland posted a video of a new Shanghai policy whereby hotels share a list of every medium- and high-risk health zone in the country, asking guests to check whether they have traveled to any of them. The result is an absurdly long list of random addresses across China including KTV parlors, student dormitories, and miscellaneous intersections. One commenter wrote: “This is a work of contemporary avant-garde art. If it were an NFT, I’d buy it.”

I’m not sure who the joke is on, me or the people handing out these lists. I asked the receptionist: “you want me to read this?” And she just started laughing. It’s things like this that undermine the seriousness of zero covid in China. Who can pretend this is a good idea?

— Don Weinland (@donweinland) August 22, 2022

source https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2022/08/beijing-protest-art-reveals-anger-over-zero-covid-policy/

Friday, 19 August 2022

UN Special Rapporteur’s Report: “Reasonable to Conclude” Existence of Forced Labor in Xinjiang

A report released this week by UN Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Slavery Tomoya Obokata stated that it is “reasonable to conclude” that there is forced labor in Xinjiang, and that certain instances of it “may amount to enslavement as a crime against humanity.” Separate from the long-overdue Xinjiang report by UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michlle Bachelet, which is expected to appear before she steps down at the end of this month, this report on forced labor provides one of the strongest critiques to date of China’s human rights policies in the region. Bloomberg summarized the report’s main conclusions regarding forced labor in Xinjiang:

“The special rapporteur regards it as reasonable to conclude that forced labor among Uyghur, Kazakh and other ethnic minorities in sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing has been occurring in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China,” Obokata’s report said. Similar policies were in place in Tibet, according to the report, which was dated July 19 and posted on Obokata’s Twitter feed Tuesday.

[…] Obokata’s report outlined two labor systems in Xinjiang, including one in which minorities were detained and subjected to work placements to give them vocational skills, education and training. Separately, surplus rural laborers are transferred into secondary- or tertiary-sector work as part of a poverty-alleviation program.

“Given the nature and extent of powers exercised over affected workers during forced labor, including excessive surveillance, abusive living and working conditions, restriction of movement through internment, threats, physical and/or sexual violence and other inhuman or degrading treatment, some instances may amount to enslavement as a crime against humanity, meriting a further independent analysis,” Obokata’s report said. [Source]

In February, the International Labor Organization (ILO) published a report expressing its “deep concerns” about China’s labor policies in Xinjiang, which include “coercive measures” indicative of forced labor. The ILO report was one of many cited in the Special Rapporteur’s this week. Finbarr Bermingham from the South China Morning Post explained the background of the Special Rapporteur and the significance of his report:

While it does not represent an official UN position – rapporteurs are independent appointees asked to investigate specific rights issues in specific regions and make recommendations – it is among the most critical of China’s human rights record to have come from within the body.

Obokata’s assessment was made following an “independent assessment of available information, including submissions by stakeholders, independent academic research, open sources, testimonies of victims, consultations with stakeholders, and accounts provided by the government”.

[…] Obokata is a Japanese scholar of international law and human rights, specialising in transnational organised crime, human trafficking and modern slavery.

He was appointed as the special rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery, including its causes and consequences, in March 2020, and has previously worked on human rights issues for the British government, the European Union and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Japan. [Source]

My report to #HRC51 on contemporary #slavery affecting #minorities is now available ⬇️https://t.co/jtBCdUz3Yo.

I highlight vulnerabilities & exploitation among #Uyghur, #Yazidi, #Rohingya & #Roma people, #Dalits/#CDWD, people of #AfricanDescent, #migrantworkers & more.

— UN Special Rapporteur Tomoya Obokata (@TomObokata) August 16, 2022

The @UN Expert on modern slavery identifies how modern slavery often directly affects and manifests against the oppressed groups, including the #Uyghur and other #Turkic people. In its finding, the rapporteur indicates that the Uyghur forced labor merits its further evaluation. pic.twitter.com/8PL1gbJWSS

— Rayhan E. Asat (@RayhanAsat) August 16, 2022

Uyghur advocacy groups around the world welcomed the Special Rapporteur’s report. The Campaign for Uyghurs released a statement calling it “an extremely important and comprehensive assessment” about abuses that human rights groups have criticized for years. The Uyghur Human Rights Project Executive Director Omer Kanat stated, “It should now be impossible for UN agencies and member states to ignore atrocities of this magnitude,” and called on the UN Office for Genocide Prevention to take action. The World Uyghur Congress described the report as a wakeup call for those refusing to address forced-labor-produced goods in global supply chains:

“The Special Rapporteur has concluded what those of us in the Uyghur advocacy movement have been saying for years,” WUC President Dolkun Isa said. “Forced labour programmes have been weaponised a tool of genocide by the Chinese Communist Party – and yet corporations around the world continue to turn a profit from atrocity, and governments refuse to legislate to put a stop to it. This report’s findings must be a wakeup call to those that have so far refused to take action on the proliferation of Uyghur forced labour made goods in global supply chains.” [Source]

The Chinese government reacted to the report with hostility. Chinese diplomats on Twitter called the evidence of forced labor “fake,” and Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin criticized the Special Rapporteur:

Certain special rapporteur chooses to believe in lies and disinformation about Xinjiang spread by the US and some other Western countries and anti-China forces, abuse his authority, blatantly violate the code of conduct of the special procedure, malignly smear and denigrate China and serve as a political tool for anti-China forces. China strongly condemns this.

[…] We solemnly urge certain special rapporteur to immediately change course, respect plain facts, observe the mandate of the Human Rights Council and code of conduct of the special procedure, perform duty in a fair and objective manner, stop using lies to stoke confrontation and create division, stop politicizing and instrumentalizing human rights issues, and stop serving certain countries’ political scheme to suppress and contain China by abusing the UN platform. [Source]

UN report finds it ‘reasonable to conclude’ forced labor is occurring in Xinjiang – SCMPhttps://t.co/Hultz8LEVK

How does China view the UN and the international human rights regime? Dr. Rana Inboden of the @StraussCenter joins us to discuss: https://t.co/KwynOPG2Rs

— ChinaPower (@ChinaPowerCSIS) August 19, 2022

In a series of moves over the past two weeks, the Chinese government has attempted to rally support for its claims of innocence in the face of growing evidence of forced labor in Xinjiang. Last week, the government submitted to the ILO the ratification instruments of two conventions on the elimination of forced labor, which, as Xinhua claimed, “demonstrates its firm position on protecting workers’ rights and interests and cracking down on forced labor.” In April, the government ratified those conventions just before Michelle Bachelet began her tour of Xinjiang, in a move that critics say was taken only to improve deteriorating Sino-EU relations.

One week earlier, China hosted a delegation of 32 diplomats from African and Asian Islamic countries on a visit to Xinjiang, where they toured three cities and met with “graduates” from “training centers,” as well as Party Secretary Ma Xingrui. In a public summary of their visit, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that “Xinjiang’s achievements in prosperity, development and human rights protection cannot be erased by any disinformation or smearing,” adding that the foreign diplomats were satisfied that the “various rights of Muslims are duly guaranteed.” Using quotes from a plethora of African diplomats who visited Xinjiang on a separate visit, a Global Times article published last month suggested that people who have not visited the region cannot criticize its human rights policies. Chinese state media has been expanding its use of foreign voices to amplify CCP talking points, as documented recently by China Media Project. As a result of these propaganda techniques, some other media commentators have amplified the conclusions of these borrowed voices.

Highlighting another example of Chinese government propaganda used to combat accusations of forced labor, Rune Steenberg at ChinaFile recently analyzed the proliferation of Uyghur influencers who share videos of life in Xinjiang using CCP talking points:

Anniguli runs video channels on YouTube and the two Chinese platforms Haokan and Xigua. The channels present her as an average, 20-something vlogger in China. In this, her 746th video, she is not promoting any fashion brands, hot new products, or trendy life-hacks. Instead, what she sells to her millions of viewers, mostly within mainland China, is the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) preferred narrative about her native Xinjiang.

[…] Anniguli is one of dozens of young, fashionable ethnic minority vloggers uploading subtle, well-produced videos that support the Party line. Since 2018, Anniguli and her fellow influencers have posted hundreds of videos to Chinese social media sites, as well as to the U.S.-based YouTube. To a casual viewer, the videos may appear indistinguishable from the slew of others shared online by vloggers every day. The hosts film themselves going about their daily lives, commenting on subjects that appear to interest them. Yet their commentary closely mimics official state propaganda, at times echoing the government’s words verbatim.

[…] We have little doubt that the government supports, in various capacities, the production of these videos. In some ways, the videos represent just the latest iteration of propaganda featuring ethnic minority citizens expressing gratitude to the Party-state. Yet, the social media market has imbued them with layers of complexity, injecting commercial motivations and individual flair into otherwise stiffly scripted content. [Source]

source https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2022/08/un-special-rapporteurs-report-reasonable-to-conclude-existence-of-forced-labor-in-xinjiang/