On the eve of the Beijing Paralympic Games, CDT presents the full-text translation of this article by Xie Renci for the health news site DXY.com. Originally published on International Day of Persons with Disabilities, the article highlights the huge gap between the promise of accessibility and inclusion for people with disabilities, and their lived reality, in China today. As part of a campaign to raise funds for wheelchair ramps, the piece argues that every member of society will benefit from accessible infrastructure and unbiased treatment. Obstruction of accessible pathways and discrimination against people with disabilities, on which the piece focuses, are long-standing problems for China’s disabled community. The hollowing out of civil society over the past decade, in particular the targeted crackdowns on advocacy organizations such as Yirenping and Changsha Funeng, has only made these problems more difficult to address. But disability rights activism has not ceased, as this call for “accessibility for all” makes clear. CDT has identified and corrected some factual errors.

Today [December 3rd] marks International Day of Persons with Disabilities.

According to the sixth national census, as of 2010, China’s disabled population had surpassed 85 million.

World Health Organization data [from 2011] shows that 15% of the global population is disabled. This suggests that 15 out of every 100 people you encounter on the street are disabled.

In reality, even if you halve this figure to account for hidden disabilities, shouldn’t about five of every 100 people you encounter have a disability? And yet, how many disabled people do you know or have you met?

Where has China’s disabled community gone?

“Accessible Facilities” That Are Anything But

Imagine that you’re a wheelchair user with limited mobility, and there’s an offline event that you have to attend today. How many obstacles do you think you’re likely to encounter on the way there?

First, you have to be able to leave your home, and that hinges on whether your residential complex has an elevator.

According to the national Residential Building Code, elevators are only required for buildings that are at least seven stories high. If you happen to live in an old complex, there’s a good chance your building doesn’t have one.

Suppose you’re fortunate enough to live in a modern complex and you manage to take the elevator down to the first floor without a hitch. The next challenge is exiting the building.

In buildings where elevators are the access point for private residences, there are typically two to three steps between the elevator and street level.

If the complex was built before the Regulations on Accessible Design in 2012, then it probably doesn’t have an unobstructed, properly graded wheelchair ramp.

Even if there is one, please check its level of incline and overall condition before you use it. If the ramp is too steep, has defects, or is uneven, and you are not careful, then you risk injury, or even death, in a fall.

In early 2020, disability rights activist [Chen] Xiaoping departed our world when she fell out of her wheelchair on an “accessible” curb in Shenzhen that was not up to code. [Editor’s note: Chen Xiaoping’s fatal accident occurred in 2021, not in 2020 as reported by DXY.]

Chen Xiaoping fell to her death when her wheelchair was caught on this pothole in an “accessible” curb in Shenzhen (press photo)

If you live in a luxury residential complex that is humanely designed and up to code, and you make it to the street in one piece, then you’re going to have to figure out how to get to the event in your wheelchair.

While each city in China is unique, city streets tend to share shockingly similar design failures.

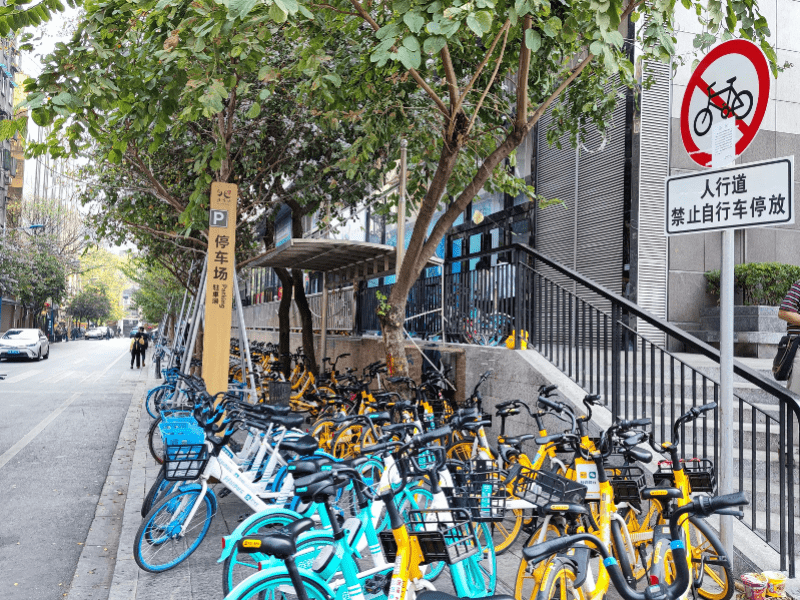

A tactile path choked by rental bikes, parked directly in front of a sign reading “Pedestrian walkway, do not park bicycles here,” and just before the covered, designated bicycle parking space. (online photo)

These dangers are not insurmountable, but getting around them is demanding and dangerous, even deadly.

In 2019, mobility rights activist Wen Jun was killed when he fell out of his wheelchair while surveying an “accessible” route in Dali. The culprit was a precipitous drop into an underground parking garage that appeared out of nowhere, without any warnings or safety barriers.

Only after Wen Jun’s fatal fall was a cordon of colored flags set up in front of the unbarricaded drop into an underground parking lot. (Baoyangcong 剥洋葱)

After navigating countless obstacles, you finally arrive safely. But your worries aren’t over–you don’t dare to drink too much water.

If the venue was built before 2012, it is unlikely to have an accessible bathroom. Even if the building was constructed after 2012, you’d still worry whether the accessible bathroom was in working order. After all, you’ve seen too many that were being used as storage spaces or were simply unusable.

An accessible bathroom, rendered inaccessible by stored items blocking the space under the sink. (Qilu Evening Post)

Once the event is over, everyone starts to leave, but you’re a bit worried. It’s gotten dark, and the trip home will be even riskier now.

These are probably only the most common day-to-day challenges faced by disabled people with limited mobility.

These challenges are even more difficult if your disability causes you pain or discomfort. If you have a sensory impairment, such as blindness, then the difficulty of traveling independently is magnitudes greater.

Now have you figured out where China’s largest minority group has gone?

Those everyday barriers—the stairwell we casually navigate, those troublesome but easily forgotten potholes—can be dangerous, even life-threatening, obstacles for people with disabilities.

The disabled are confined to their homes because there is a lack of compassionate city-planning and accessible facilities that are dependably up to code.

For disabled people, accessible facilities are their water, their air, their path to independence and freedom.

Accessible facilities make it safe for people with disabilities, the elderly, pregnant women, and children to move through and utilize a space. No construction project is complete without these amenities.

Article Seven of the Law on the Protection of Persons with Disabilities emphasizes the importance of accessible facilities. The reality is that, due to design flaws, lack of maintenance, and other factors, not only have accessible facilities failed to remove the obstacles that confine the disabled to their homes, they may have become yet another stumbling block impeding safe movement.

The Invisible Obstacle: Structural Ableism

When you hear the word “disabled,” who do you think of?

Do you think of Paralympic athletes earning glory for their countries; world-renowned scientist Stephen Hawking; Zhang Haidi, chair of the China Disabled Persons’ Federation; or some other disabled person lauded in the media whose name you can’t quite remember?

Though they are of different ages, occupations, and genders, they have all “conquered life’s challenges” and attained a level of “success.” In short, they’re all “strong.”

And the majority of readers’ comments on these articles tend toward: “How optimistic!” or “Such strength!” or “You remind me how lucky I am.”

But the disabled are simply ordinary people with certain limitations.

As the media continues to focus on backward, cliched stories of “strong” individuals living with disabilities, the public may think, “I won’t experience the same difficulties she does because I’m not disabled,” or “Thank god I’m not disabled, otherwise my life would be miserable.”

Disability is not simply a fixed individual identity, but also a function of limitations imposed by society.

If glasses suddenly disappeared, how many people would immediately become “disabled” due to their nearsightedness?

If traffic signals could only be understood by distinguishing red from green, then those who can’t tell the difference wouldn’t be allowed to drive. But in Japan they’ve invented a [red] traffic light with an “X”, so that color-blind drivers know when to stop. As a result, the inability to differentiate between red and green is no longer an obstacle to driving.

Disability is by no means “someone else’s business,” and it’s not simply an individual matter, but is rather a societal issue brought about by design flaws and institutional shortcomings.

The media’s image of the iron-willed “disabled superhero” who overcomes all obstacles stands in stark contrast to the reality of discriminatory, often invisible, oppression of people living with disabilities.

The media’s favorite disabled person by far is Wu Xiao. After losing her eyesight as a child, she surmounted incredible challenges, scoring 470 on the gaokao and gaining admission to Nanjing Normal University to study applied psychology. [Editor’s note: Wu Xiao attended Nanjing Normal University of Special Education (NNUSE), not Nanjing Normal University.]

However, in 2020, Shaanxi Normal University rejected her application to their master’s program in the same field, claiming that “the university is unable to accommodate blind students.”

One of the admissions officers had the audacity to ask, “How can the blind even attend school?” completely ignoring the fact that Wu Xiao had fulfilled her course requirements at Nanjing Normal and had received her undergraduate degree. [Editor’s note: Wu Xiao was still a fourth-year student at NNUSE when she applied to Shaanxi Normal University.]

This dismissive attitude towards people with disabilities is discriminatory and fails to consider their true capabilities. Moreover, the Law on the Protection of Persons with Disabilities requires that schools not yet equipped to support students with disabilities must do all they can to create a supportive environment, and not just take the easy way out by rejecting them.

Social obstacles may be tangible, like stairs, steep slopes, or barriers, but they can also be intangible practices or attitudes, such as rejecting someone’s application on the grounds of disability, or assuming that the disabled are somehow “unsuitable.”

The physical obstacles we see on the street keep people with disabilities confined to their homes. The intangible bias of individuals and institutions prevents the disabled from having a voice in society.

Everyone Needs Accessible Facilities

The idea that “disability is a personal issue” comes from a misunderstanding of the limitations and fragility of human beings, the immediate consequence of which is the belief that “accessible facilities are only for people with disabilities.”

Have you ever carried heavy luggage up or down stairs?

“I always hated the train trip home from university. I would have to carry two suitcases up and down an endless procession of stairs. Some of the sloping walkways were so steep that I nearly tumbled down them along with all my luggage.” It’s at times like these that you really need accessible facilities.

Have you ever pushed a stroller?

In early 2020, because some New York City subway stations lacked accessible facilities, a mother fell while carrying her stroller down the station stairs, and both mother and child were killed. [Editor’s note: this appears to refer to Malaysia Goodson and her daughter, Rhylee, who fell in January 2019, not 2020. Ms. Goodson died, but her child survived.]

Have you ever been injured in an accident?

Someone once asked online, “If you have a broken leg and there isn’t a Western-style toilet, how do you go to the bathroom?” The response was full of dark humor: “You can practice one-legged squats.”

Even if you’ve never had to carry heavy things, push a stroller, or been injured, you’re eventually going to get old, right?

“When you’re young, you don’t think about how your legs give out when you’re old, and how absolutely grueling it is to climb the stairs.”

For most people, growing old is a process of gradually losing physical function. When you’re young, you don’t think twice about the odd slope or pothole, but these things can cause serious injury.

Once we reach old age, we must face our limitations and human fragilities. In this sense, we will all be disabled someday.

In the talk “Hostile Homes,” Professor Li Dihua of Peking University’s College of Landscape Architecture recounts how a respected senior colleague was badly injured after tripping over a five-centimeter [less than 2 in.] protrusion. Unable to continue the career he cared about so deeply, the man succumbed to despair and passed away soon after.

“Everyone Needs Accessible Facilities” is just not a slogan.

We all live in a world full of uncertainty, where the limitations of the human body and of society can easily render any of us disabled.

Accessible facilities “concern us all”: For every single one of us, there will come a time when we require assistance.

We need to take action now, rather than waiting until we are elderly or injured, or need to carry luggage or push a stroller, to realize just how important accessible facilities are.

[As leading Japanese feminist thinker Chizuko Ueno told NHK in the broadcaster’s “Last Lecture” television series,] we need to form “a society where we can be frail or weak and still feel safe,” because “we won’t always be strong.”

The slow process of eliminating entrenched biases against people with disabilities demands that we clear our streets of tangible obstacles, make it possible for more people with disabilities to leave their homes, and create a society where the able-bodied feel that accessible facilities are for them, too.

DXY has decided to make a small contribution: we’re partnering with the Zhejiang Foundation for Disabled Persons to donate several accessibility ramps.

Of course, these ramps alone can’t resolve all mobility issues, but at least they’ll come in handy when we find ourselves challenged by a set of stairs or a steep slope.

For more details, please see the poster below. (Note that the ramps will not be as steep as those depicted in the image.)

Our ultimate hope is that someday there will be no need for these temporary accessibility ramps, and that cities won’t be cluttered with dangerous obstacles that impede the free movement of us all. [Chinese]

This poster shows an illustrated depiction of the temporary ramps that DXY and the Zhejiang Foundation for Disabled Persons fundraised for in December 2021. One ramp was donated for every hundred views of the video embedded at the end of this article.

Translated for CDT by Hamish.

source https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2022/02/translation-chinas-invisible-disabled-community/

No comments:

Post a Comment