Investigative journalist Peng Yuanwen is known for his reporting at The Beijing News, Vista and ifeng.com, as well as for his witty commentary on Mark Zuckerberg’s notorious 2016 Beijing “smog jog.” But long before that, he worked as a machinist at a stationery supplies factory in the city of Dongguan, Guangdong Province. In the longform photo essay translated below, which was deleted from his personal WeChat account for violating “the Provisions on the Administration of Internet User Public Account Information Services,” Peng Yuanwen returns to the now-defunct factory to explore its abandoned workshops and empty dormitories, and to revisit his own memories of the place where he once lived and worked:

I came back to the factory at just the right time: any earlier, and I wouldn’t have been able to get in; any later, and it would probably be gone.

After a business trip to Shenzhen last July, I decided to go back and pay a visit to the Nanzha Leco Stationery Factory in Humen Township, Dongguan. I was prepared to be disappointed: I assumed I’d just take a quick look from the outside and leave. I certainly wasn’t expecting to march right into what was essentially a no-man’s land. But in fact, the place was deserted. The factory had been closed for a year at that point, and no one was looking after it, so I was able to go in and wander about freely, seeing the past laid out before me.

I worked as a machinist in the engineering department from 1997 to 2001. I’m now in my forties. Those were probably the most important four years of my life. It was the first time I was living and working on my own. I grew into someone who knew what he wanted, and who was willing to work hard to get it. I hadn’t been back since I left 19 years ago. I left the stationery factory (and factories altogether) for the same reason I had been so hellbent on leaving Yueshan Dongfeng Motor Factory in Sichuan Province before—I didn’t want to spend my entire life in a place with no chance for advancement. This time, though, I wasn’t so impulsive. I had learned patience and self-discipline.

My memory is horrible. I don’t know what day I arrived, or what day I left—I’d really have to think about it just to figure out what years these things happened, and even then I couldn’t be certain. (After I left, I went to live with my cousin. That was the year 9/11 happened, so it had to be 2001.) There are a lot of things I have forgotten. I only remember fragments.

Thanks to the internet and smartphones, I know my trip was July 25, 2020. I took a lot of pictures that day, and meant to write about it shortly afterward, but I put it off for a year. I didn’t have the time or energy to really polish this piece, so the following are just some thoughts I jotted down as I looked through the pictures. It’s just something I wanted to write for myself, as a memento.

- The Pavilion

This is the pavilion outside of the factory. On the day I was hired, I got my work clothes and my green plastic food bowl and reclined on a seat here (just like the man in the photo). I felt completely relaxed. We use that phrase a lot—“like a heavy load has lifted”—but I never experienced it as viscerally as I did that day in this pavilion. I remember that feeling of tranquility and peace of mind like it was yesterday. Finally, I no longer needed to worry about food, or about where I’d sleep that night.

Later, I read a newspaper article that asked laborers what they worried about the most. It wasn’t backpay, nor was it illness: over 90 percent worried most about not being able to find work. If you don’t have a job, you don’t have food to eat or a place to live. It used to be that you could sleep on the streets (the weather’s great in Guangdong), but by then, there were security teams on patrol, and you could be taken into custody and sent back to your city of origin.

I remember one time, I was walking down the street in Dongguan and saw someone lying motionless on the side of the road. I thought he was dead. I kept looking back as I walked. Suddenly, his fingers moved. I was hit with a wave of sadness—not because I was unable to help him, but because I wondered whether I might end up like him one day. I didn’t have a dollar to my name (well, maybe I had a couple), so finally finding a job made me feel incredibly lucky.

Oh, I almost forgot to mention this: the workshop that hired me had air conditioning. The factory had Hong Kong investors. (The best factories in Dongguan were American and European; below that, Japanese and Hongkongese; then below that, domestic and Taiwanese. Some Taiwanese factories were even worse than the domestic ones, I don’t know why.) There were three factories in the park: World Wide Stationery Manufacturing, Leco Stationery Manufacturing, and Tatt Shing Metal Work Manufactory. All of them belonged to World Wide Stationery Holdings Co. Ltd. We mainly made those little clips for the inside of binders. Although our product was tiny, I heard we held a third of the global market share.

- The Dormitory

This is the dorm room I lived in for four years. There were eight to a room. I think I was on the bottom bunk in the bottom right corner. I can’t remember the names of any of my roommates. Most of them came from state-run enterprises further inland. We were all technicians, mostly from state-run enterprises. I faintly remember a guy from Hubei Province. He was older than me, tall and skinny, very thrifty. But he donated quite a bit during the floods in the south in 2008. I think it was 50 or 100 yuan.

Most of us bought a woven mat to put on the bed, a pillow, and a red plastic bucket for our toiletries. I’ll always remember the quilt I bought off the street near the entrance to the factory. It was army-green and looked like military surplus, but it was actually made out of cheap, low-grade cotton. I used it so much that over time, the cotton wadding shrank into the corners, leaving just two thin layers of cloth in the middle. The winters were extremely cold. I actually could have afforded a better quilt—at one point, I was making over a thousand yuan a month. But no one was going to spend tens or hundreds of yuan on a quilt. Everyone was like that.

Looking at this bed reminded me that we didn’t have any dressers to store our clothes. I kept mine in a snakeskin bag that I put underneath the bed. I used to stack my books on the bed and against the wall. I collected more and more books as time went on. I was quite proud of my collection. The most important thing I took away from my time at the stationery factory was learning how to educate myself, becoming self-taught.

The walkway outside my dorm room—this is where I used to spend all night reading “The Biography of Hu Shi.” Mr. Luo Zhitian’s “The Dream of a Chinese Renaissance: A Critical Biography of Hu Shi” [in Chinese] is the book that has had the biggest influence on me. It was the first time I realized that there were philosophies other than Marxism out there to make sense of the world, and it’s what made me a liberal.

Years later, I would write about this in an essay: “I read in the walkway until midnight (turning on the light would disturb my roommates) and told myself I should go to bed because I had work in the morning (I worked 11-hour shifts at the time). But I ended up lying in bed, unable to fall asleep, so I went back out to the walkway and continued reading under the dim yellow light.”

This is what it looks like outside the dormitories. My room was in that building farthest away in the picture, on the third floor, second door from the right. I don’t know what was out in the courtyard that day, but it reeked.

Many years later, I saw a picture just like this in the news. A worker ended her life by jumping from the building (the building on the right is the women’s dorm). They said it was because of a dispute over a cell phone. Leco employees were standing below in their khaki uniforms.

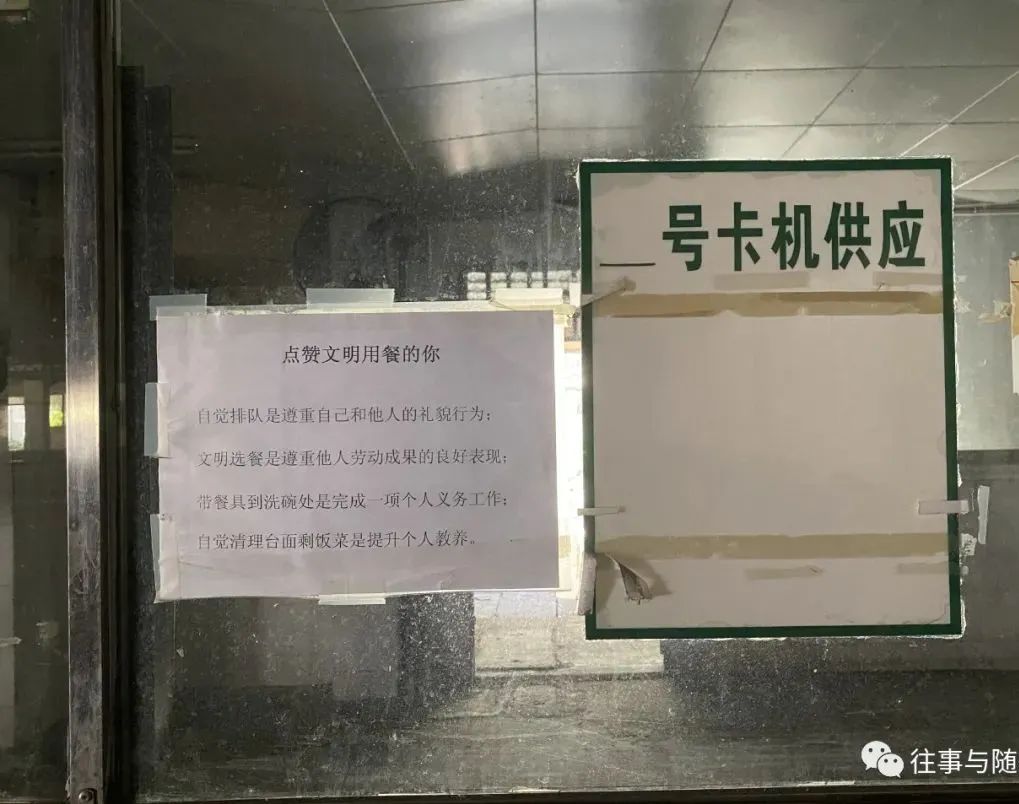

- The Dining Hall

This is the dining hall. There were three dining halls: Dining Hall A was for upper and middle management, Dining Hall B was for technicians and lower management, and Dining Hall C was for regular factory workers. I ate in Dining Hall B.

Sign at left: “Thank you for being a civilized eater. Waiting in line shows respect for yourself and others. Taking food politely shows your respect for the fruits of others’ labor. Taking your dishes to the wash station is fulfilling your duty. Wiping down the tables makes you more cultured.” Sign at right: “No. ___ card machine provided.”

At the time, there were a few thousand people working in the factory. Long, bustling lines formed at every mealtime. I used to rush back to my room at noon every day, grab my bowl and chopsticks, and race over to the dining hall. If I was quick enough, I could finish lunch early and get back to the workshop in time for a ten- or 20-minute nap. If not, it was easy to doze off in the afternoon while working the machines, which could be dangerous.

This is the dining hall where middle and upper management ate. I had never been in there before. This time, I finally got to go in and take a look around: it was empty, too.

- The Factory

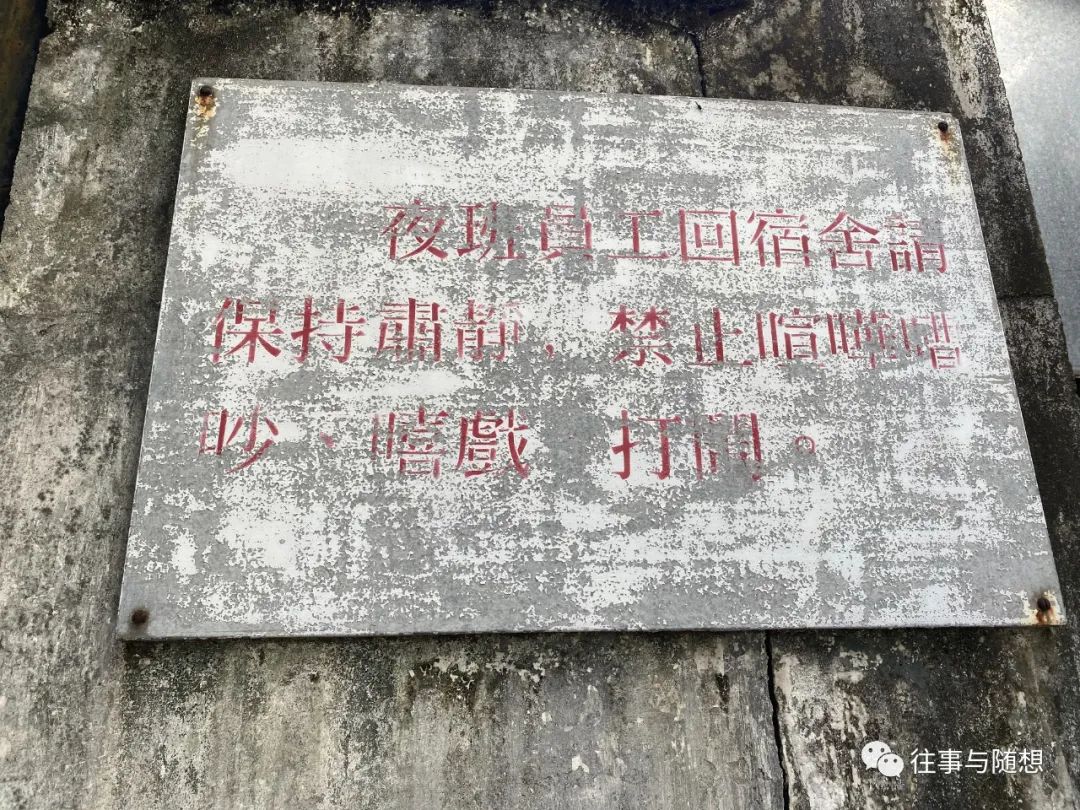

“To night shift staff returning to the dorms: Please keep quiet to avoid disturbing others.”

“Display identification upon entry. Protect the factory. Remain vigilant. World Wide Stationery Factory.”

“Cell phone use is prohibited on factory premises.”

“Notice: Do not bring any camera or video recorder into the workshops. No photographing or video recording is allowed. Thank you for your cooperation. By the order of the General Manager.”

From the dining halls, I was able to enter the factory area unimpeded. Not a soul was there.

This is the Leco factory where I worked: a four-story factory building. The engineering department was on the top floor. I was in the machinists’ group, which included turning, clamping, planing, and milling. There was also the grinding group and the processing center group. We mainly made molds, which required a relatively high level of technical ability.

There are metal catwalks on the side of the building. I used to stand on the fourth-floor catwalk, hanging pieces of metal and finished molds.

The Engineering Department

None of the other doors were locked—just the door to the engineering department. I couldn’t manage to pull it open, no matter how hard I tried. What a shame to come all this way and not be able to get in.

The last date on the board was from June 2019.

Someone had written “5S,” which made me think about how often people talk about “Danshari” [the art of decluttering] these days. Actually, factories were talking about this stuff 20 years ago, and they were better at it, in my opinion. It’s just that the words we were using weren’t to the liking of white collar and middle class folks.

After a year, I was promoted from machinist to foreman. And I wasn’t half bad at it.

I picked up some habits working in a factory. For example, I absolutely cannot stand when someone tries to cover up their mistakes. In the world of machining, if something’s wrong, it’s wrong. Scrap is scrap. No one quibbles about it, because a product made from a faulty mold will turn out wrong, or not turn out at all. Quibbling is pointless.

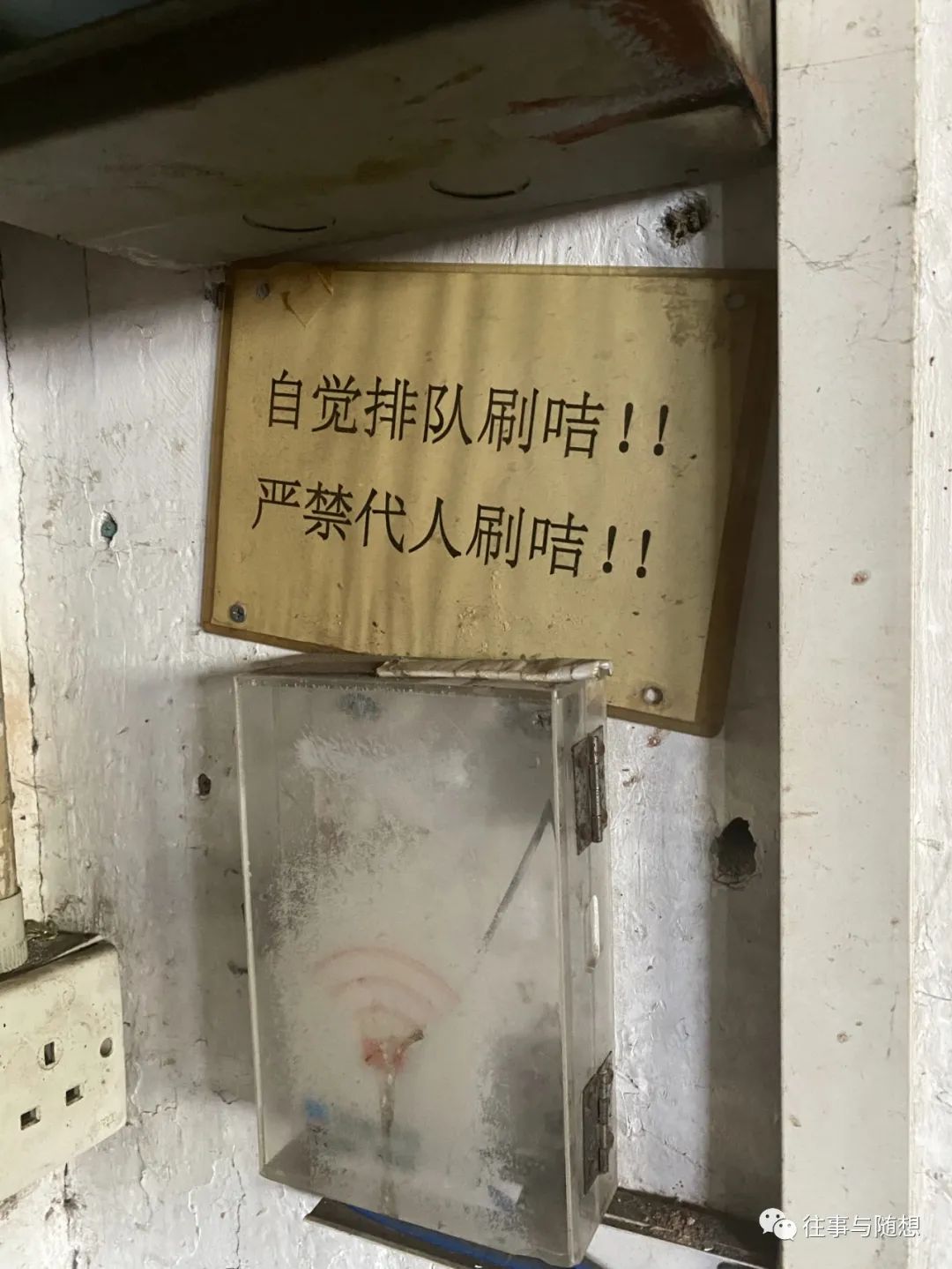

“Line up to swipe in! No swiping for others!”

We punched in with a time card. As I wrote in a letter to Southern Weekly, “Last month I had 314 hours logged on my time card.” Even though I worked every day of the month, with no days off, I still worked over 10 hours a day.

Unable to get through the door to the engineering department, I had to settle for the next best thing. Following the catwalk, I managed to squeeze through an exit leading to the second-floor injection molding department (where they used the molds we made). At any rate, the layout is roughly the same.

“Injection Molding Production Staff Distribution Table”

Engineering was basically arranged like this: Management was mostly people from Hong Kong. The supervisors were the real ones in charge. Below them were general foremen, then foremen, who were responsible for different groups, normally for two shifts at a time.

My supervisor was surnamed Xiong. He was really good to me. He pushed for me to become a foreman and encouraged me to take the Self-Taught Higher Education Exam. He lent me money to buy a computer. He even invited me to dinner at his house during Lunar New Year. I remember he came to see me before I was promoted. I thought he wanted to talk about work, but we ended up talking about politics, and berating certain people. I later wrote an essay called “Buru Xiangwang Yu Jianghu” [“Better to Forget One Another in the Rivers and Lakes,” based on a classical reference found in Zhuangzi], because I had forgotten all of the names of the people I worked with in the stationery factory. Because of this essay, I was able to get back in touch with Old Xiong, which made me really happy.

Three years ago, Old Xiong came to Beijing, and we met for dinner. We had a great time, and kept telling each other that we hadn’t changed a bit.

Why show pictures of the men’s room? Because this was heaven for the night shift. We used to smoke cigarettes in there all the time. And I never drank more Nescafé in my life.

Farewell, Leco Stationery Factory.

- The Library

This is where I read and studied: an ancestral hall repurposed as a library. This is where I borrowed that copy of “The Biography of Hu Shi.” When I was preparing for the self-taught exams, I was here reading 7-9 p.m. every night. I even wrote about it in the essay “On the Road to the Library.” I won’t say more about that here.

Now the library’s gone. It’s been turned back into an ancestral hall.

These are biographies of two famous Nanzha locals. They give you some idea why this hall was once a library.

Thank you, Nanzha Library.

- Fellow Workers

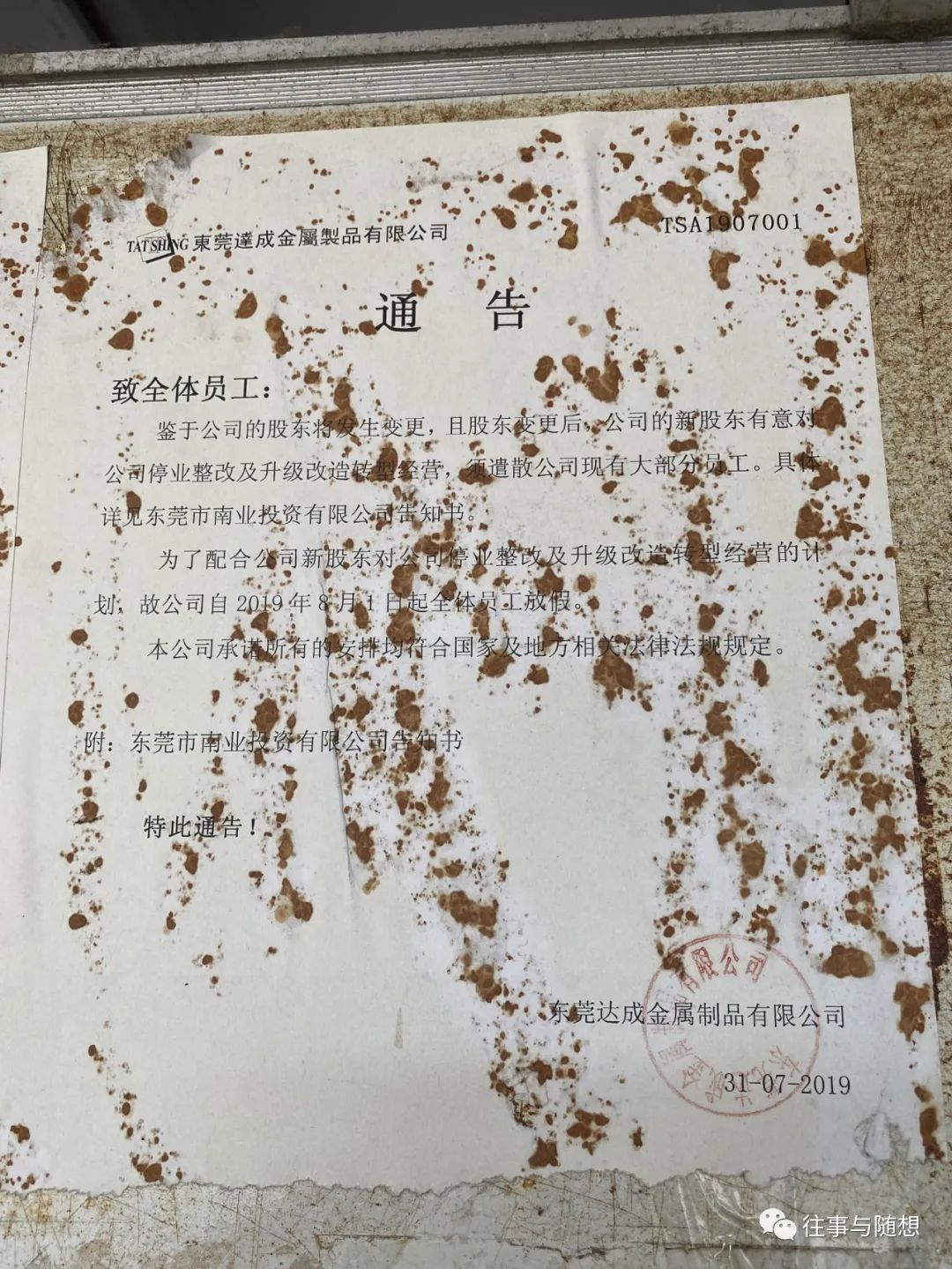

A notice, dated July 31, 2019, announcing layoffs at the factory

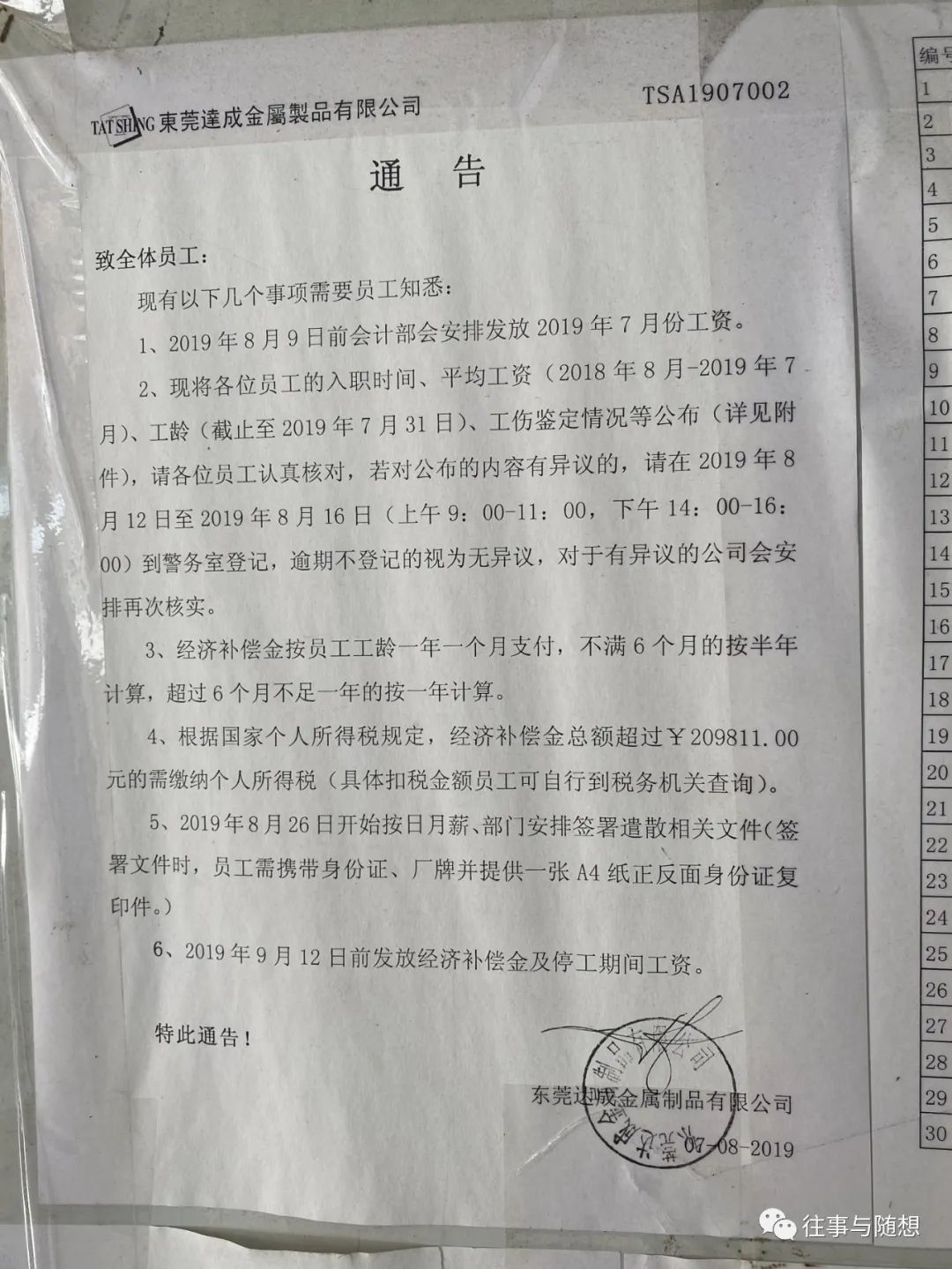

A later notice, dated August 7, 2019, explaining salary payment and compensation for the factory workers

Tatt Shing laid off most of their workers in August 2019, and the factory ceased operation. I couldn’t find any info about the World Wide or Leco factories on the walls. I think they stopped production before Tatt Shing.

I photographed all the lists of laid-off workers that I could find.

I once saw a documentary called “Factory of the World,” which opens with a long shot of an assembly line. It’s the longest single shot I’ve ever seen, slowly panning across workstation after workstation along the assembly line, and all those factory workers working so quickly and diligently. Watching their silhouettes and their faces, I was moved to tears.

I get the same feeling looking at those lists of names. Reading through their names, dates of hire, salaries and length of service, I can’t help but wonder: Where did they come from? What did they do here? Where did they go?

Most of them were earning 3000-5000 yuan a month. Some who had been working there for 20 years were making just over 3000. My guess is that they worked the assembly line. There was no salary differential on the assembly line, whether you’d been working there ten years or 20. A few suffered on-the-job injuries. Even for less-serious injuries, they could get compensation worth seven to nine months’ salary.

The longest-tenured employees had worked there for over 30 years (which means they arrived in the 80s), and quite a few were there over 20 years. Not only did a generation spend their youth here—for some, it was half their lives.

- Epilogue

Looking back, the person I need to thank the most is myself. I’m proud of the person I was 20 years ago. I have no bones to pick with him. He did well. I just remembered: when my parents came to Beijing not long ago, they mentioned that I used to send a thousand yuan back home every month. I did that for a year, before they told me to stop, which I did. I had completely forgotten about that. I’m honestly impressed that I was able to save that much money. I wasn’t making much more than a thousand yuan a month at the time.

I also have to thank my superiors. In addition to Old Xiong, my general foreman was also really nice to me. Because he knew I was preparing to take the self-taught exam, he gave me a special exemption from working overtime so that I could go study at the library in the evenings. I don’t know how I got so lucky—at every turn, it seems like I had superiors who were very good to me. I hope I can measure up to them, although I know I will always fall short.

Next, I need to thank those hard-working, diligent Chinese who worked by my side. If you don’t hold us back, we can do amazing things. And even when you do, we will find a way.

I also need to thank this factory. It gave me a job and four relatively stable years. I don’t really have any hard feelings towards my bosses there. Most of the time, the majority of the bosses at Chinese enterprises are working to make our lives better, not worse. Returning to the present day, consider companies like Didi and Meituan: not only are they making our lives more convenient, just think about all the people who are able to find jobs and make a living because of them. If only they had been around 20 years ago.

As for the country and the government, that’s a stretch. If they want thanks, they’ll have to wait at the back of the line. And I’d have to really rack my brains to figure out what they’ve given me… so never mind, it’s too much bother. People are always complaining online about the jerks and scumbags they’re dating, which just goes to show how much everyone hates being strung along and cheated on. The way I see it, we should apply these same standards to other areas of life.

All right, I suppose I’ll leave it at that. [Chinese]

Translation by Little Bluegill.

source https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2021/08/translation-photo-essay-remains-of-the-nanzha-leco-stationery-factory/

No comments:

Post a Comment