During the recent resurgence of COVID-19 in Xinjiang, self-media photojournalist Zhang Xinmen documented the situation in Karamay, the northern Xinjiang city where he lives. On his WeChat public account, Zhang posted a photo essay titled “Reflections on Isolation in the Xinjiang Epidemic Situation,” in which he compared the measures used to enforce the lockdown with the safety breaches that magnified the death toll of the 1994 Karamay Fire disaster. The next day, he was visited by authorities and given an official talking-to—which he covered in a follow-up essay. Both essays have been archived by CDT Chinese, and are translated below:

August 28th: Reflections on Isolation in the Xinjiang Epidemic: No Evil is So Small It’s Good

It was almost midnight last night when the community administrator sent the following news: “Epidemic prevention and control has reached the most crucial stage. Everyone must refrain from secretly going out without permission…”

This morning, just past 9 AM, loud voices in the courtyard woke me. Someone in the group said everyone had gone down for a walk. An hour later the manager said: “All residents can go out now, tear the sticker strips off your doors. It’s been hard on everyone, staying home for so long…”

True enough, right? Although not a single pneumonia patient has been discovered in Karamay, it has been through more than 33 days of stay-at-home lockdown.

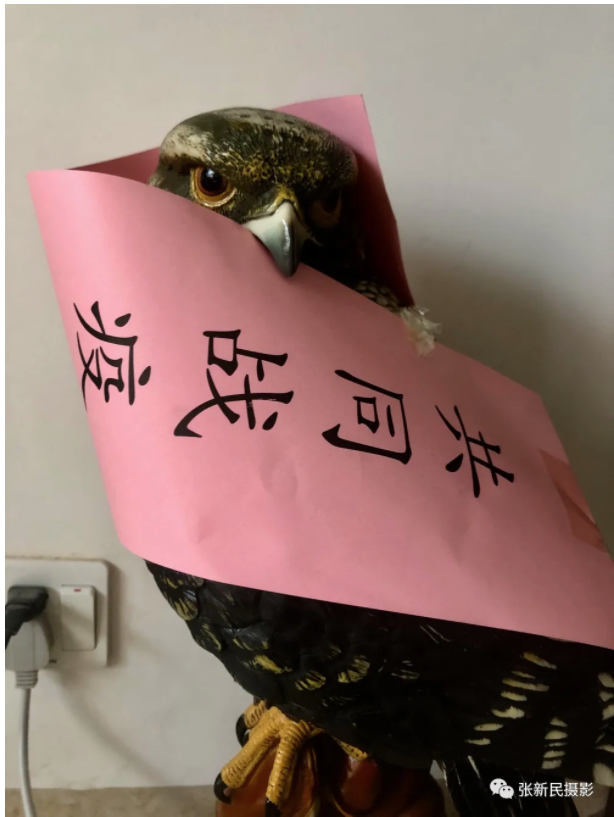

- “Commonly Fight the Epidemic; Wishing You Health”

What this type of management is aiming for: If the resident pushes the door open from inside, the seal will fall down, then you can just….

I carefully peeled it off to keep as a souvenir!

Previously, all garbage was disposed of by volunteer help. Today I saw a pile of those seals already in the garbage can, along with a whole case of Big Wusu beer.

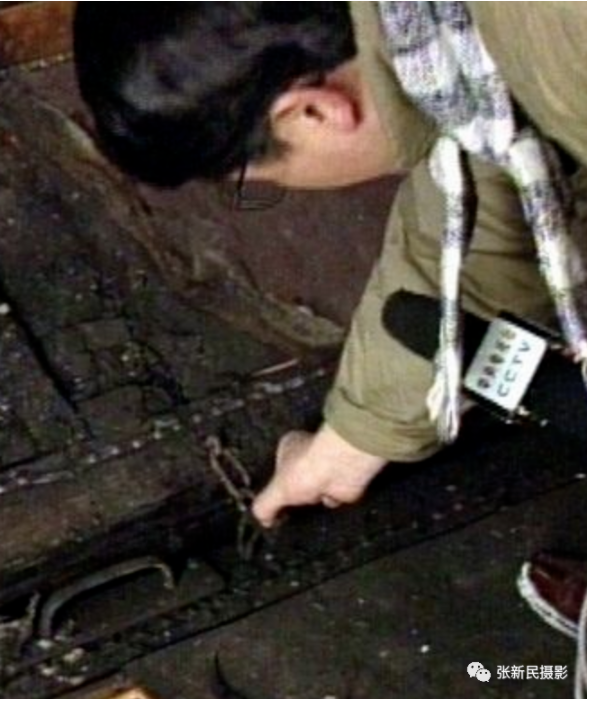

Our district is fortunate. In a friend’s neighborhood in another part of Karamay, it’s the same as before, you can’t go downstairs. When he went out to do his DNA test, he discovered his building’s door like this:

Outside the building door, a hole had been bored and a steel rebar inserted.

The intended effect of this type of management: If residents come downstairs, they still can’t push the door open from inside to go out.

Actually, since August 1, they’ve been implementing this sort of thing on building doors over in Urumqi:

Karamay is definitely drawing from Urumqi’s experience, adopting those methods in some districts. From the very beginning, I’ve been worried that these methods could lead to an awful situation in case of emergency conditions. Residential buildings have electrical appliances furnace equipment that could start a fire. That [rebar isolation method] could create maximum danger for someone fleeing fire.

People mustn’t forget the “12.8” incident. This is Karamay’s eternal sorrow, and its eternal shame. On December 8, 1994, in Karamay City, Xinjiang, a vicious fire broke out leaving 325 dead and 132 wounded. Among these were 288 middle and elementary students. [The Karamay Fire is associated with the infamous phrase “everyone sit down. Don’t move. Let the leaders leave first,” reportedly shouted to keep the children in place.]

Several years later, on a Karamay street, I saw a billboard that said, “Please allow the children go first,” and I felt society was progressing.

For several years after the accident, I worked continuously in a building across from Friendship Theater. I saw those ruins every day. Finally, it became a public square full of mosaics, but as before there was an unresolved, indescribable sorrow about the place.

In case anyone has a bad memory, here is a screenshot from an internet video back from the time of the fire:

On the right side of the image are the students’ seats. On the left side, that brightness is the emergency exit in the south wall of the assembly hall, near the stage. When the fire happened, that dazzling radiance was locked, impassable, and that meant death.

A journalist examines that securely closed iron door.

At the time of the January outbreak, Karamay implemented this type of isolation method on some residents in a few districts:

Under what circumstances will such measures be implemented to regulate people’s movement?

I recall when filming a program about mental disorders, there was a specialized hospital that had two tightly-locked steel doors. But these steel doors were certainly not locked from the outside. Rather, after visitors pressed a doorbell, the nurses of the ward would first look through a small window, then open the door from inside.

Viewed purely in terms of isolation methods, those in the current epidemic are not as good as the mental patients’.

I don’t know how the fire department feels about these sorts of sealing measures since the beginning of this epidemic, but we don’t always assign or incorporate blame after an accident.

No Evil is So Small It’s Good; No Good is So Small It’s Not Worth Doing

[Chinese]

CDT Chinese editors note that Zhang’s account of the talk with police the next day, translated below, was quickly deleted:

August 28: Reflections on Isolation in the Xinjiang Epidemic, a Follow-Up: Did This Really Earn Me an Official Visit?

Just after midnight, someone incessantly rang my doorbell.

“Who is it?”

“From the task force!”

When the door opened, eight burly fellows came in.

The light in the living room was broken, so there was only the dining room light for illumination. Under the poor lighting, what I saw opposite me was a dense, dark human barricade.

Yesterday morning, a friend told me on WeChat that a friend of his, someone on official duty, had asked him to tell me to delete my “Reflections on Isolation in the Xinjiang Epidemic: No Evil is So Small It’s Good” article, and warn me not to “ask for trouble.”

And now, trouble had arrived!

They got straight to the point. The social stability maintenance leader questioned me on the following points:

- Why hadn’t I been answering the phone?

I really hadn’t turned on my mobile. People at work posts keep their mobiles on at all times, but for someone like me who has been away from my shut-down work unit for more than three years, I keep the phone off because I don’t want scammer calls. Also, I’m in the habit of using WeChat on my computer.

- Why didn’t I go through conventional channels to report the problem?

What, I still needed to get company approval?

- Yes, I do!

But posting an article online is itself a conventional channel, right? Otherwise how did I get the information out to all of you?

- That won’t do…

(Not to mention I don’t know where they are working out of. I just know I can’t go out of the district gate, and their office is presumably empty…)

I asked them if they were all responsible for safety here? What I meant to do as a social media user was nothing more than call attention to this issue. Door-sealed residents will have difficulty if they need to flee for their lives. If we wait until another fire tragedy, and once more go and say a sealed door is the culprit, what use is it at that point? Didn’t they pay attention to hidden safety hazards, and seek to lessen incidents of disaster? Don’t office buildings usually have fire alarm drills? Aren’t fire escape signs and firewalls everywhere? [I told them I felt that] as leaders who had seen my article, they should personally go to those districts to see if the steel rebars are still in place. If so, they should remove them without delay, solve the problem. They shouldn’t first dispose of the person who raised the issue.

Mao Zedong said: “All men must die, but death can vary in its significance. To die in the interest of the people is greater than Mount Tai.” If it were Zhang Side, he would certainly get rid of the rebars sealing the doors, and smash open the locks on the doors.

At this point a young fellow who hadn’t said a word said he was part of the community, that the circumstances I’d described were already being rectified, and that for some time now the community had been discussing various new measures and ways.

I asked if he would write some of this down, thit was just the result I was after. He said that was a no-go. I fetched paper and pen to record it myself, then asked him to sign, but he wouldn’t sign.

I asked one of them what department he was with. He said he was a specialist, and in charge of us.

I told him his wording was incorrect, that he “Served the People,” that he wasn’t “in charge” of anyone. I said that if he wanted to take that attitude, he could please just leave now, that it was my home, and he was not welcome here.

The atmosphere was a bit strained, everyone’s voices got quite loud… at this time, two police officers entered. I said how about you all leave, and I’ll go with you.

Without waiting for me to put on my shoes, a group of them rushed downstairs, leaving just the two civil police and one neighborhood official.

The big police officer began looking at my article. We began going through the details paragraph by paragraph.

He said that posting self-media in no way illegal. As for whether or not the work unit thought it violated regulations, that was unclear.

As to whether I should’ve used the “12.8” example, he said he himself was a survivor of that fire. He was one of seven who jumped from the second floor to save their lives. The whole class had a total of 42 people inside.

About whether it was appropriate to contrast the mentally diseased with isolated people, I said I thought I had a fairly exhaustive understanding of [the situation of] mental patients. I explained that it is even illegal to lock mental patients up from outside.

The other officer said he’d seen pictures of locks on doors, and he confirmed it was indeed the case.

Regarding the rebar pictures, I wanted to maintain confidentiality for the source of the images, but there was also evidence the pictures were not fakes. The officers and the neighborhood comrade, after hearing of that district, claimed it was an isolated case, and that they didn’t currently know the situation there.

The neighborhood comrade said that all districts currently had ended that sort of situation. If needed, tomorrow I could be taken to the site to understand the situation.

The police comrade said that the reason it had been done was that originally, when the epidemic began, pressure was high. People traffic volume (or some term like that) between Urumqi and Karamay was 30,000 or more. People were still going out at 4 AM for visits or strolls. Isolation was very difficult, and there were many details. But as he didn’t yet have leadership approval, he couldn’t provide me pictures.

According to the neighborhood comrade, there were always community personnel and volunteers outside unit doors, on duty. But he couldn’t provide pictures at this time. They would talk it over tomorrow.

As of now, my online article doesn’t need to be deleted. I’m waiting to get more material, perhaps I’ll do another photo post.

It was very late when they left, nearly 2 AM. Laying down on my bed, I couldn’t fall asleep for a long time.

Counting on my fingers, the “assembly” that had just occurred was 12 people. Couldn’t that already be considered “illegal”? Fortunately, everyone was wearing face masks.

Yesterday I saw this sentence: Life’s greatest freedom is the freedom to narrate. In other words, as long as you wish to possess freedom, who can keep you from being free? [Chinese]

Translation by Alicia.

source https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2020/09/translation-xinjiang-lockdown-karamay-fire-comparison-brings-police-visit/

No comments:

Post a Comment