Friday, 30 July 2021

Outspoken Tycoon Sun Dawu Sentenced to 18 Years in Prison

Sun Dawu has been sentenced to prison for 18 years and fined 3.11 million yuan for “gathering a crowd to storm state institutions, obstructing public service, picking quarrels and provoking troubles, disrupting production and operation, conducting coercive trade, illegal mining, illegal occupation of agricultural land, [and] illegal absorption of public deposits.” Sun and 19 other people affiliated with his agricultural conglomerate, the Dawu Group, were arrested in November due to a conflict with a local state-owned company and, some allege, his outspoken political commentary. Sun accused the government of covering up a 2019 African swine fever epidemic and publicly supported Xu Zhiyong after the lawyer called for Xi to resign for mishandling the COVID-19 epidemic. This will be Sun’s second stint in jail. He was convicted in 2003 of “illegal fundraising,” a pocket crime often used to target the state’s perceived enemies, and spent five months in prison. At The Wall Street Journal, Chun Han Wong reported on Sun’s unusually speedy trial, which included marathon court sessions that extended over 12 hours:

The court said Dawu Group and other defendants were given “corresponding penalties,” but didn’t provide details. Mr. Sun’s 19 fellow defendants were given jail sentences ranging from one to 12 years, while the company was ordered to pay the equivalent of more than $130 million in fines, restitution and refunds for money they were deemed to have raised illegally, their defense team said.

[…] Lawyers involved in the Dawu case have accused authorities of handling the prosecution with undue haste, saying they were given less than two weeks to read through about 350 sets of case files. In a statement issued Wednesday after the verdict, the lawyers said the case was handled at a speed that suggested that “this wasn’t a normal legal trial.”

[…] Some of Mr. Sun’s supporters took to social media to voice dismay with the verdict. “His life is full of legend and struggle, and his circumstances are the common circumstances of Chinese private enterprises,” Zhao Xiangsong, a blogger, wrote on his verified Weibo social-media account. “How the rights of private enterprises can truly be protected is a matter that concerns the future and fate of this country.” [Source]

"Sun Dawu has made extraordinary contributions to improving the life of Chinese citizens living in rural China," @RamonaLiCHRD, senior researcher and advocate for CHRD, said in a statement. https://t.co/zvizYWBEzd

— CHRD人权捍卫者 (@CHRDnet) July 29, 2021

While awaiting trial, Sun was kept in residential surveillance at a designated location (RSDL). Suspects in RSDL can be held incommunicado at secret locations for up to 6 months without access to legal representation. Six Dawu Group employees, including three of Sun’s children, were also detained in RSDL. They were kept in windowless rooms—Sun said he did not see the sun for three and a half months—and not provided the opportunity to bathe themselves regularly. Sun said, “under RSDL, I suffered terribly, life was worse than death!” Jin Fengyu, a Dawu Group executive also held in RSDL, said the lights in her cell were left on 24 hours a day. “A camera watched me and because of the lack of privacy, I never once could bathe,” she added.

Before his arrest, Sun was something of a philosopher. The Dawu Group operated under a corporate philosophy of Sun’s creation, “constitutional labor-capital republic,” whereby property was held communally and employees elected the board of directors. Sun also had a penchant for public speaking and writing. After his arrest in November, CDT translated an op-ed Sun wrote in 2009, in which he opined on the meaning of true heroism:

The moment I shed tears in court I felt that the best people in the world and the worst people in the world were all in jail. There’s nothing scary about jail, jails are just another place that people go to. I believe that people often have no control over whether things turn out good or bad. Sometimes you want to be a good person but are unable to. Sometimes bad people want to be good, but are also unable to. Death row inmates, too—a lot of them wanted to be good people but wound up in jail. They feel like fate is playing tricks on them, not that their situation was caused by their human nature. Deng Xiaoping said, “Good institutions can make bad people good; bad institutions can make good people bad.” I believe these words.

At the time I did not despair. Rather, I felt a type of power. I have never despaired before, I honor the principle of caring about right and wrong, not about winning or losing. “No matter what everyone else does, I must take the high road.” I was very stubborn as a child. People said that I was an ox [牛], that the last character in my name “Wu” [午] had grown a head. I’m not saying this to brag or to be self-deprecating, this is just a description of my personality. When I set my mind on something, I will complete it; when I set my mind on a way forward, I will pursue it to the end.

[…] At first, compromise is a virtue. It is good forgiving evil, and evil conceding to good. If you compromise once, people usually will forgive you, but if you compromise for your whole life, people won’t usually consider you a hero. This is to say that the wise use the method of compromise to enlighten society, but they are not likely to become heroes. Heroes must have a solemn quality and the willingness to work at something even if success is impossible. Heroes are those who consciously choose the difficult path. [Source]

Sun’s evident fearlessness (in a statement he said, “With my character, I can’t give others a flattering smile. I can’t do it. That has doomed my destiny”) allowed him to offer frank criticism of the Chinese Communist Party. In doing so, he often found himself allied with prominent lawyers and activists. At The New York Times, Paul Mozur documented Sun’s long-standing relationships with China’s activist community:

Under Mr. Xi, a series of crackdowns on civil society has thinned out the ranks of liberal-minded lawyers and independent journalists. Xu Zhiyong, one of three lawyers who represented Mr. Sun in 2003 and a prominent activist, was detained last year after he urged Mr. Xi to resign, writing to Mr. Xi that “you’re just not smart enough.”

At the time, Mr. Sun spoke up for Mr. Xu. This time, there were few left to speak up for Mr. Sun, who argued repeatedly of the need to push back against power grabs and political bullying.

[…] Among Mr. Sun’s supporters was the Nobel Peace laureate Liu Xiaobo, a human rights advocate who died in detention in China in 2017. Mr. Liu once said Mr. Sun posed a “tremendous challenge” to the Chinese system because he possessed both courage and resources.

“The government,” Mr. Liu wrote, “will definitely go after him with murky laws.” [Source]

I was surprised to realize Wu Xiaohui and Ren Zhiqiang both got 18 year sentences before Sun Dawu got the same today. It’s incredibly harsh, but I suppose it’s the new standard in Xi Jinping’s China. A good reason for business leaders to retire early. https://t.co/qhLrsbO4Ew

— Paul Mozur 孟建國 (@paulmozur) July 28, 2021

Sun’s case is in some respects similar to that of Ren Zhiqiang, the outspoken tycoon sentenced to 18 years in prison after criticizing Xi Jinping. Both cases indicate the government’s limited tolerance for criticism, even from formerly powerful billionaires. In February, Li Yuan of The New York Times wrote a profile of Sun that argued his case exemplifies the dramatic roll-back of China’s political and economic liberalization since Xi’s rise to power:

China was, and remains, an authoritarian country under Communist Party rule. But the nature of its authoritarianism has become much harsher under Xi Jinping, the party’s top leader since late 2012. Mr. Sun’s case exemplifies the country’s drastic turn from a nation striving for economic and social, if not political, liberalization to one increasingly operating in an ideological straitjacket.

[…] Unlike 2003, few are clamoring for Mr. Sun’s release. A former journalist who wrote an influential article about Mr. Sun in 2003 couldn’t find a place to publish a commentary. A close friend of Mr. Sun’s said he had been warned by his state security minders not to talk to journalists. Even people who had received assistance from Mr. Sun in the past didn’t respond to my requests to talk, even off the record.

“Sun Dawu was lucky in 2003,” said Mr. Chen, the veteran journalist. “He was suppressed by the government, but he was rescued by the public. He paid his price, but it was relatively small.” [Source]

source https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2021/07/outspoken-tycoon-sun-dawu-sentenced-to-18-years-in-prison/

Thursday, 29 July 2021

Translation: “The Country Has Gone Dark.” Li Huizhi’s Last Words

Li Liqun, a liberal political commentator who wrote under the pen name Li Huizhi, and has lived under constant surveillance for nearly four years, took his own life by drinking pesticide on July 22. Li had asked repeatedly for a medical reprieve after he suffered a stroke in March 2020, but his requests were ignored, according to his suicide note. Radio Free Asia reports:

Li Huizhi, 62, died on July 23 in a hospital in Guangdong’s Huizhou city after being rushed there and placed on a ventilator in an attempt to save him.

His friend Li Xuewen told RFA that the poet had posted a suicide note online before taking his own life.[…] “This deterioration in his living circumstances made him desperate,” Li Xuewen said. “The stroke had left him disabled, and yet he was still being treated as a stability maintenance target.” [Source]

CDT has been unable to locate any of Li’s poetry online, but a collection of his political writing is archived at Boxun.

CDT’s full-text translation of Li’s suicide note follows:

At the beginning of Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao’s administration, I published articles online calling for equality and justice, criticizing corruption in all its forms, and pushing for systemic reform… Time and again, I was named among the “hundred great public intellectuals of the nation” and “hundred most influential bloggers in China.” Yet since the new administration took power, and especially with the arrival of the “great Chinese dream,” the vise has been tightening around me. When the 19th Party Congress came in 2017, I suddenly became classified as a “ministerial-level” target of stability maintenance (the “only one” in Huizhou, an “honor” of which I was informed by numerous domestic security officers). And I am “jointly managed” by the cities of Huizhou and Heyuan, as my hukou is in Longchuan County in Heyuan. When I go back to my hometown, I am minded by Longchuan domestic security. Since I rarely make that trip, I am usually minded by Huizhou domestic security (they slacken a bit during important holidays). They monitor my phone, and when I leave the city, or when friends come to Huizhou to visit, domestic security invariably “has a word” with them (friends have been barred from meeting me for meals in Huizhou on multiple occasions).

I had a stroke in March 2020, making me a “grade 2” on the disability scale, and can only walk with a cane. I asked several times to be exempted from surveillance. Domestic security answered by the book: they would bring my request to the higher-ups. As for when I would be granted a reprieve, they did not have the power to make that decision.

On the afternoon of June 19, 2021, I was “paid a visit” at home by Mr. Xu, the [head] political instructor for municipal domestic security, along with Brigade Vice-General, Mr. Tan, and Battalion Political Instructor, Ms. Huang (I suppose this was in preparation for the centennial of the founding of the Party the following week). I asked them once again: I have fallen ill and am still suffering from the after-effects of the stroke. I am not capable of “opposing the Party” anymore. May I be granted a reprieve? Their response was the same as last year!

On the morning of June 29, two days before the centennial, Brigade General Jiang and Vice-General Tan visited me again (clearly because of the upcoming anniversary). General Jiang said he hadn’t seen “Old Li” for a long time … I brought up my “situation” again, but they didn’t answer me directly.

I sign all of my writing with my real name, whether I publish in China or abroad; every article I write is within the scope of what is constitutionally permitted and based on constructive criticism. Nothing I have said is extreme [by any measure]. Why, then, am I a target of “stability maintenance”? … I did not voice a single critical opinion for six months following my stroke, yet I am more watched, not less, on every holiday. Before the centennial this year, Vice-General Tan and Instructor Huang added me on WeChat (previously, only Brigade General Zhou and Instructor Xu had added me). There were the two “sympathy calls” before the anniversary. Then on the morning of July 16, Officer Zhou came yet again to have a “heart-to-heart” …. You can imagine what all of this activity portends.

The sages have warned time and again: “Stopping the mouths of the people is harder than stopping a flood. You may block the water, but if it breaks through, it is sure to claim many lives; so too if you block the people.” And now? Those in power do not sit and listen to the opinions and criticisms of intellectuals, but instead deploy the machinery of the dictatorship and the policy of carrot-and-stick, forcing intellectuals to succumb to reality. No one dares to petition, no one dares to dissent. The country has gone dark, and the temples ring with a chorus of sycophancy …. By “putting power in a cage of regulation,” they have put critics and dissidents in a cage!

What I want is this: I want the leadership to sit down and listen calmly to what dissidents have to say, instead of always sending public security to knock on their doors …. The Great Helmsman said, “Unless in the desert, wherever there is a crowd there will be a left, right, and center; so it will always be.” Since there is a left, right, and center, why must one side always be quashed by the apparatus of the state? Why can’t you see hope in the opinions of the political opposition? The Party has held power for 70 years. [Your] July 1 speech impressed on us a great retreat to your founding creed, that the overarching dictum of “progressing with the times” has turned into “regressing with the times.” You leave no room for hope! Could this be the misfortune of being born a Chinese?

The July 1 festivities are a veritable banquet of materialism, calling to mind Dickens: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times”—anyone who can leave has already gone to imperialist America, or Canada, or Australia, while the rest of us can only “single-mindedly follow the Party” … Yet “the International working class shall be the human race” is undoubtedly historical nihilism! …

There is no hope for the future! It has never been more hopeless! Of course there are some who maintain that “dawn will break”—because they watched “The Eternal Wave” one too many times when they were young ….

If I’ve said it for ten years I’ve said it for 20. What else is there to say? I’ve said it all in vain!

Every day my body is tormented by the aftermath of my stroke, while my spirit is crushed under an unbearable weight. Now I must “wave goodbye with my sleeve / not taking a whiff of cloud.”

Today I “annihilate myself from the Party and the people.” This has nothing to do with law enforcement in Huizhou—I repeat: Since 2017, the domestic security officers in Huizhou City and the Huicheng district have always been civil. They are of fine character, and are simply following orders. They have never treated me poorly. The onus is on their superiors—they are responsible for my death!

I ask my family not to hold a funeral for me. Scatter my ashes in the East River. Do not hold onto them.

Li Huizhi (Li Liqun), July 22, 2021 [Source]

source https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2021/07/translation-the-country-has-gone-dark-li-huizhis-last-words/

Wednesday, 28 July 2021

Tuesday, 27 July 2021

Coming Forward Against Singer, Young Woman Resparks China’s #MeToo Movement

China’s entertainment world has been shaken by a young woman’s accusation that singer-actor-model Kris Wu date raped her and other unnamed teenage girls. By coming forward, Du Meizhu, the 18-year-old accuser, may have reinvigorated China’s recently moribund #MeToo movement, which has been hamstrung by official censure. At The New York Times last week, Elsie Chen reported on the allegations against Kris Wu and their significance for China’s #MeToo movement:

Mr. Wu’s accuser is Du Meizhu, a university student in Beijing who said she first met him when she was 17. She said she had been invited to Mr. Wu’s home by his agent with the suggestion that he could help her acting career, according to her social media posts and the interview with Netease, an online portal. Once there, she was pressured to drink cocktails until she lost consciousness, she said, and later found herself in his bed.

[…] “This incident shows that nowadays people will no longer swallow insults and humiliation and be afraid of slut shaming,” said Feng Yuan, a feminist scholar and activist. “People increasingly want to speak up and make themselves heard.”

[…] Ms. Du said she felt helpless when she learned that Mr. Wu specifically targeted young women like her. “Indeed, we are all softhearted when we see your innocent expression, but that does not mean that we want to become playthings whom you can deceive!” she wrote in a post on Weibo. [Source]

An AFP report detailed the outpouring of support Du received on social media after coming forward:

“My life has definitely been ruined,” Du said. “Although I have only ever slept with Wu, the public has long thought that I’m damaged goods,” she wrote in a Weibo post with more than 7.3m likes.

[…] The allegations triggered an outpouring of solidarity from Chinese women, with the Weibo hashtag “girls help girls” gaining more than 130m views by Monday.

The hashtags “Du Meizhu interview” and “Du Meizhu demands Wu Yifan announce he is quitting the entertainment industry” gained 1.8bn and 440m views respectively on the Twitter-like platform. [Source]

Chinese authorities and others have suppressed the #MeToo movement. Courts often rule against sexual assault plaintiffs and Weibo recently suspended activist Zhou Xiaoxuan’s account for unspecified violations. But a number of state-affiliated media outlets have publicly condemned Wu. Although Beijing police have not yet brought charges, they are investigating his behavior. At Variety, Rebecca Davis reported on official statements intimating legal consequences for Wu:

China’s strictly controlled state broadcaster CCTV issued a statement Tuesday calling for the creation of better industry-wide mechanisms to “force artists to improve their moral character and raise the bar for becoming a star.”

“Being an artist is not just a profession – it’s more about taking on social responsibility. Now that the Kris Wu incident has blown up to such proportions, it is no longer mere entertainment industry gossip, but a legal case and public incident of great influence, requiring a comprehensive investigation by the relevant departments to resolve any doubts,” it said.

[…] In a Weibo missive re-posted more than 2 million times, the central committee of the Communist Youth League wrote: “What we are really concerned with isn’t celebrity gossip, but about good and evil, beauty and ugliness in society, about fairness and justice in a society with rule of law.” [Source]

This could be, as thread says, China’s Weinstein but only because previous #MeToo moments involved establishment figures (TV anchors, senior academics) and somewhat politically ‘threatening’ accusers (students, feminists), while Kris Wu is just a crappy Canadian rapper https://t.co/TnxqJdZPZk

— Robert Foyle Hunwick (@MrRFH) July 21, 2021

Such official statements are likely not an embrace of #MeToo but rather part of a broader effort to curtail the influence of “stars” and an accompanying fandom culture that has authorities worried about Chinese youth’s “erosion.” Celebrities that violate state- or society-imposed moral strictures often find themselves the target of official criticism. Earlier this year, a surrogacy scandal involving actress Zheng Shuang demonstrated state media’s willingness to weigh in on celebrity gossip.

It soon became clear that the condemnation of Wu did not imply support for Du Meizhu. At Vice News, Viola Zhou detailed multiple official outlets’ accusations that fame, not justice, was Du’s principal motivation for accusing Wu:

State-run newspapers then attacked the woman for hyping up her allegations for fame. The official Legal Daily called her a “malicious marketer.” The Beijing Daily said instead of reporting the case to police, Du posted her allegations online to seek attention and followers.

[…] Zheng Churan, a feminist activist who has campaigned against sexual harassment in China, said many victims have resorted to posting their experiences online because it would be even harder to uphold their rights through official channels.

“If authorities label this as fame-seeking… it might put the victims under more public pressure,” she said. “Eventually, the victims would have no way to defend their rights, and the assailants would be emboldened.” [Source]

Whatever state media’s intentions, Du’s public account of her ordeal has inspired other women to come forward with their own experiences. In response to such aspersions, Du wrote: “So many women who were deceived have reached out to me; I’ve already done all I can to give them a voice […] You can say I’m sensationalizing to become famous online—whatever you want to say is fine, I don’t care… I’ve tried my best.” At The South China Morning Post, Mandy Zuo reported on two allegations against powerful academics in the wake of Du’s public stand against Wu:

Zhou Xuanyi, an associate professor at Wuhan University and a well-known online commentator on women’s rights, has been suspended from teaching after a woman alleged that he date raped her, the university said in a statement last week.

[…] It was also revealed earlier this month that the Anhui Agricultural University in Hefei, Anhui province, is probing a senior official for sexually harassing a female student after the student, Zhang Xiaoxiao, took to social media several days after the Wu scandal broke.

[…] The accusations against Wu by influencer Du Meizhu could be the beginning of a new wave in China’s entertainment circle, said Hou Hongbin, a feminist writer in Guangzhou.

It would at least encourage more women to come forward in the future when encountering similar situations, she said. [Source]

source https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2021/07/coming-forward-against-singer-young-woman-resparks-chinas-metoo-movement/

Cartoons and Commentary: Flood Victims and Rescuers “Are Human Beings, Not Bowls of Soup”

At least 63 are dead after intense flooding in Henan. Over 160,000 first responders have been sent to Henan to aid rescue and recovery efforts. Although the crisis is not yet over, the machinery of the state is already attempting to recast events in a generally positive and heroic light. CDT has obtained and translated two censorship directives: the first ordering the media to focus on disaster recovery and avoid using “an exaggeratedly sorrowful tone” in coverage; and the second requiring vendors “not give interviews to foreign media, and deny the other side any opportunity to take quotes out of context and distort the facts.”

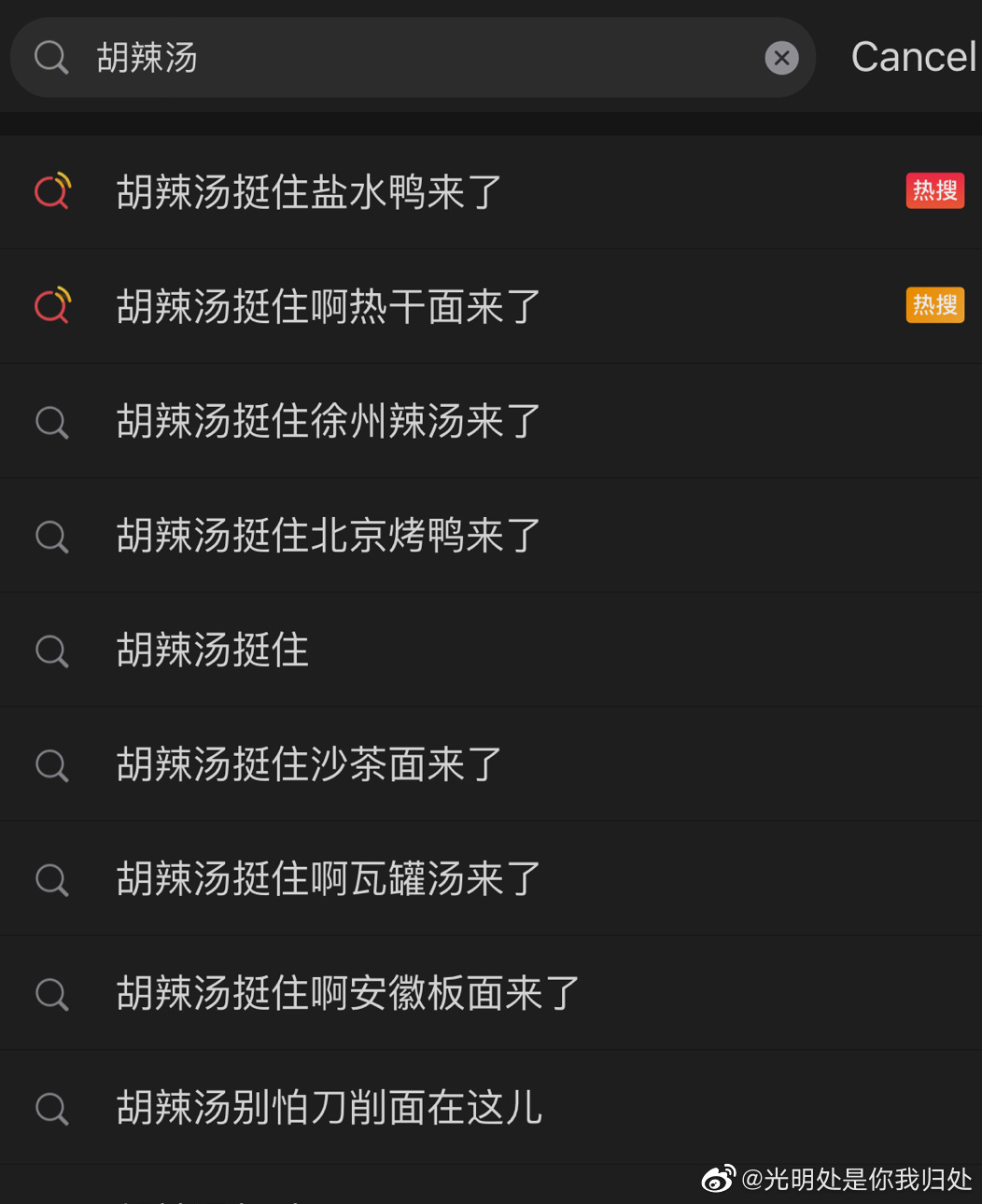

One viral cartoon on the relief efforts rendered the incoming first responders as regional cuisines and Henan as a bowl of Hulatang, a spicy, peppery local soup—adding a cutesy flair to life-and-death rescue work. The personification rubbed many the wrong way, bringing back memories of support for Wuhan hot dry noodles and Xinjiang cotton at the expense of solidarity for actual people. The cartoon is also reminiscent of the cartoonish anthropomorphization of construction equipment used to build emergency hospitals early in the COVID outbreak, which was first adopted by state media from social media users, and then targeted by a directive against “overly entertaining and jocular content.” A number of Weibo users found such cartoon abstractions dehumanizing, and viewed them as an indictment of society’s ability to face grave tragedies directly. As Weibo user @光明处是你我归处 wrote in response to the cartoon, “They are human beings, not bowls of Hulatang”:

Artist 陈小桃 shared the cartoon on Weibo with the caption: “Hang in there, Henan Braised Noodles. Hot Dry Noodles have arrived. We’ve all arrived!  / We are ‘with’ you [punning on an ancient character for Henan]/ Stand strong, Henan. We’ve all arrived.”

/ We are ‘with’ you [punning on an ancient character for Henan]/ Stand strong, Henan. We’ve all arrived.”

Hulatang quickly became a Weibo trending topic:

Stand strong, Hulatang. Nanjing Salted Ducks have arrived.

Stand strong, Hulatang. Hot Dry Noodles have arrived.

Stand strong, Hulatang. Xuzhou Spicy Soups have arrived.

Stand strong, Hulatang. Peking Ducks have arrived.

Stand strong, Hulatang.

Stand strong, Hulatang. Shacha Noodles have arrived.

Stand strong, Hulatang. Earthen Pot Soups have arrived.

Stand strong, Hulatang. Anhui Noodles have arrived.

Don’t be afraid, Hulatang. Knife-cut Noodles are here.

@光明处是你我归处: They are human beings, not bowls of Hulatang. Those risking their lives to rescue others, answering distress cries, and wracked with fear and anxiety are people, too, not token foodstuffs like Hot Dry Noodles, Nanjing Salted Duck, or satay noodles. This is a disaster, and if you can’t face that reality, the least you can do is not be an ass about it.

A number of Weibo users concurred with @光明处是你我归处’s post:

礼榆Stella: I don’t understand why food must always stand in for place names. Because it’s cute? Is it appropriate for the media to write headlines like this during a serious disaster? To make it cute is to dumb it down. This is the worst form of infantilized infotainment.

樺笙:I hate speaking of disasters and other serious issues by personifying food: “Hold on Hulatang, Hot Dry Noodles and Soup Dumplings are coming to help.” Content writers can make stuff like this to inspire people, but it’s inappropriate for the media. Personifications like this infantilize disasters. If the people in disaster zones are Hulatang, then what are the floods and storms? Too much broth? There are many ways to inspire people, like posting your hopes on Weibo or sharing touching videos. But when journalists dumb down coverage for the sake of more clicks they abandon linguistic rigor. The official media, whose fundamental job is to reassure people, is not only shirking its responsibility to the written word, it has become complicit in fanning the flames.

呀-粉孩儿:I feel like they’re missing something core to being human: the spirit to face disasters directly. When everything becomes infotainment, infantile, frivolous, and gamified, we don’t have to face up to any serious topics—we can just spend our days laughing or giggling at the funny bits, crying or sobbing at the touching bits.

shutupCollins:You could say things are exactly the same as during the pandemic. Looks like this year was spent in vain.

呀-粉孩儿: This sort of language pollution has intensified since last year. I see it and want to puke.

霜糖琉璃猫: Big Brother A-Zhong has nannied us into senility: turned every citizen into a giant infant. [Chinese]

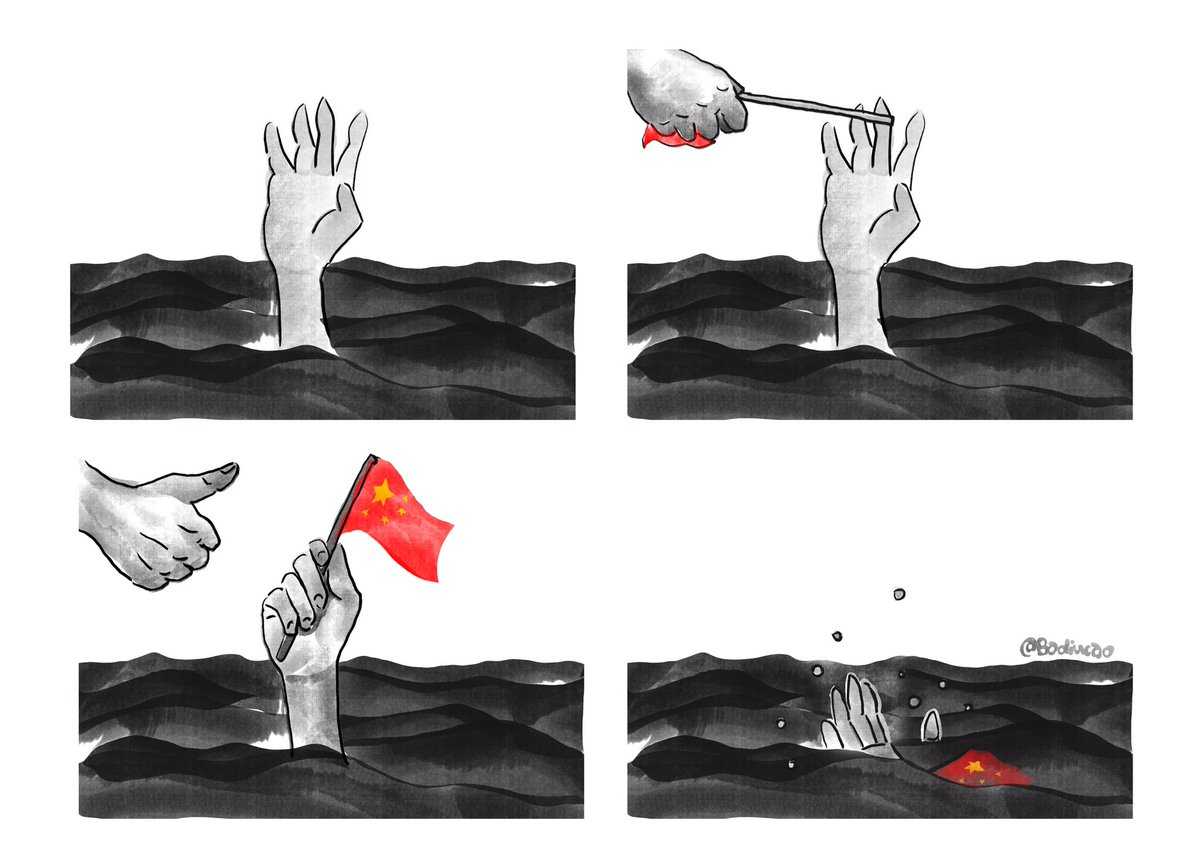

Dissident cartoonist Badiucao posted his own interpretation of China’s flood rescue by riffing on a popular meme created by Russian artist Gudim in 2017. His creation satirized state-led efforts to portray disasters as moments of national greatness:

Henan Flood Rescue with Chinese Characteristics by Badiucao

A number of Chinese internet users expressed similar sentiments, expressing anger at the conditions that allowed the flood and the rescue efforts that have followed it:

傅芮冈:Almost all the horrific scenes coming out of this rainstorm are from the city, but the place of true horror right now is the countryside. You won’t be able to see their faces, nor will you be able to hear their voices. #Henansoncein1000yearsstorm

Summer_L100: What I want to know is, where did this once-in-5,000-years statistic come from? China only has 3,000 years of recorded history. I figure they assume the more they talk up the seriousness of the natural disaster, the smaller the government’s own issues will seem: “It’s that old man in the sky who killed everyone…nothing to do with the government.” Also, those photos of advancing floodwaters don’t look like rain, but like haphazard dam releases.

insituQ:“There are mechanisms to shut down operations during storms, but they are not instantaneous. As for who has the power to shut down the subway, it’s quite possible that the subway management group [Zhengzhou Metro Group] doesn’t have it, and that they must seek higher-level approval before commencing. Shutting down the subway is a societal issue. — a municipal subway employee from a city in the south of China, who was unwilling to reveal their name

vm_cmj: What happened in Zhengzhou is the same thing that happened in Wuhan: when disaster strikes, the governmental departments have no idea what’s happening or what they should be doing, the media doesn’t know what they’re allowed to report, and everyone looks up helplessly, awaiting orders from the top. But the omnipotent higher authorities are too busy dreaming of a strong nation, and nobody dares to tell them what’s going on. And so from top to bottom, the Party-state is a nation of sleepwalkers.

Xhnsoc_Redflag: European leaders should reflect on the large-scale loss of life induced by the floods.

孟煌: Humanity’s disasters are similar in that they all involve human misfortune and the loss of life. But it is in the management of these disasters that governments reveal their differences. In an open society, people come first. In a closed society, scoring political points and allowing officials to “save face” comes first. People’s lives come second because stability is paramount.

MianMaoKu:After the Wenchuan earthquake, didn’t they establish building quality standards and increase supervision of construction projects? After the Wenzhou high-speed train crash, what did they do to avoid another similar tragedy? After the coronavirus spread, did they establish a first-response warning system for infectious diseases, rather than arresting people for “spreading rumors?” Time and again, we witness tragedies that “move the nation”; time and again, we grin through our tears to “triumph over tragedy.” When disaster strikes, average people are simply left to fend for themselves. When the next disaster strikes, the body count is certain to be even higher. [Chinese]

With contributions from Cindy Carter

source https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2021/07/cartoons-and-commentary-flood-victims-and-rescuers-are-human-beings-not-bowls-of-soup/

Monday, 26 July 2021

Minitrue: Warn Vendors Against Foreign Media Interviews on Henan Floods

The following censorship instructions, issued to the media by government authorities, have been leaked and distributed online. The name of the issuing body has been omitted to protect the source.

Currently many foreign media are conducting on-the-scene coverage near the Jingguang road tunnel. Given the sensitivity of this topic, it could easily attract a high level of international public attention and stir up international public sentiment. It is recommended that each administrative district office assign personnel to thoroughly conducting door-to-door visits to each local business, warning all these vendors to sharpen their vigilance, not give interviews to foreign media, and deny the other side any opportunity to take quotes out of context and distort the facts. If any such incidents are discovered, notify the administrative district office or report it to the police. Pay attention to work method: absolutely do not use SMS or WeChat messages, please go door-to-door to give spoken notification. (July 24, 2021) [Chinese]

This suspected local “grassroots propaganda notice” has been circulating online from various sources following last week’s disastrous floods in Henan. An earlier directive published by CDT urged domestic media to focus on post-disaster recovery and not to “publish unauthorized images showing dead bodies, take an exaggeratedly sorrowful tone, or hype or draw connections to past events.”

NPR’s Emily Feng reported on last week’s events at the tunnel named in the instruction above:

Only a few hundred feet north of Wang’s restaurant is the Jingguang traffic tunnel, built in low-lying, formerly swampy land. Water began rushing into the mile-long tunnel last Tuesday, creating a strong current against which Wang and her son fought to stay upright.

“Around 20 or so people – male, female, old, and young – were also trying to get home in the storm, so we linked arms, with the front pulling the back row forward, and the back pushing the front onwards,” says Wang. She made it home, a few hundred feet away, in just over an hour.

Those inside the tunnel were less lucky. Nearly 200 cars inside became stuck in several feet of water, then began floating. Several drivers behind them stayed in their cars, believing the pause to be traffic. At least two passengers never made it out.

[…] As of Sunday, rescue teams were still draining water from two of three sections of the tunnel. When NPR visited the tunnel three days after the flood, hundreds of police hovered around the site, shooing away curious onlookers while several mud-caked cars sat nearby, having been dredged from the waters. [Source]

Anger has flared online in the wake of foreign media coverage of the floods. Many reports questioned aspects of the authorities’ preparation for and handling of the floods. These include the provincial capital Zhengzhou’s “sponge city” flood control strategy, and the decision to keep the city’s subway running for as long as it did. (More than 500 people were trapped underground when the system flooded, and at least 12 drowned.) Much of the criticism has focused on Robin Brant of the BBC. The organization has suffered a backlash in recent months over its coverage of mass detentions in Xinjiang, leading one of its reporters to leave the country.

Several foreign journalists have described uncomfortable scenes while reporting from the flood zone:

exactly the same thing happened to me yesterday at almost precisely the same location… I got reported to the police

— Dake Kang (@dakekang) July 25, 2021

Later on we realized that was actually a screenshot of @robindbrant from the BBC, and that Weibo users had been calling for a manhunt to catch the “rumormongering foreigner.” They’d been photographing Mathias for days and posting shots online saying he must be the BBC

— Alice Su (@aliceysu) July 25, 2021

Prior to this we had been chatting w people on a street where several huge holes and opened in the road. Shopkeepers were distressed about insufficient govt help to drain water from their underground stores, w all their goods still submerged after four days pic.twitter.com/4bVFsujhhn

— Alice Su (@aliceysu) July 25, 2021

There were many other ppl in Zhengzhou and the surrounding worse-hit areas who were open and even eager to talk about the destruction and difficulties they’re facing. But this crowd seemed really angry and eager just to tell the foreigners off (有人说“我们要捍卫中国”)

— Alice Su (@aliceysu) July 25, 2021

We weren’t the only foreign reporters who encountered hostility in Zhengzhou this week: https://t.co/ttCiC0CrlE

— Alice Su (@aliceysu) July 25, 2021

Su’s colleague Mathias Bölinger also described the incident on Twitter:

Just to give you guys an idea what environment leads to this kind of incident. This is a post by Henan’s Communist Youth League asking netizens to follow around @robindbrant and report his whereabouts. https://t.co/y18TTR9JY4 pic.twitter.com/mPoETs3sVu

— Mathias Boelinger (@mare_porter) July 25, 2021

How times have changed… https://t.co/REP0dUSHUH

— Mathias Boelinger (@mare_porter) July 26, 2021

Su was previously detained and expelled from Inner Mongolia while reporting on language protests in the region last September. Bölinger described mounting interference with foreign journalists’ work at Deutsche Welle in March following the release of this year’s annual report from the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China:

Mathias Bölinger, a DW journalist based in China, said while the situation in China has deteriorated over the last few years, it has dramatically worsened over the last year. “It has become harder to find interviewees and scheduled interviews are often cancelled,” Bölinger said.

He added that Chinese people are less willing to talk about political topics and are often warned not to give interviews to foreign journalists. Foreign correspondents are also facing more and more restrictions in other aspects.

“Previously, foreign journalists were only followed by Chinese police in sensitive regions like Xinjiang, Qinghai, and Inner Mongolia, but now foreign journalists are also being followed in major cities, such as Hangzhou,” Bölinger said. “In addition, quarantine rules, such as isolation rules, are being used arbitrarily, especially in Xinjiang.”

9/ Informational access is diminishing. 88% said interviews were cancelled by subjects were barred from speaking to a foreign journalist. This represents an increase from 76% in 2019.

— Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China (@fccchina) March 1, 2021

Since directives are sometimes communicated orally to journalists and editors, who then leak them online, the wording published here may not be exact. Some instructions are issued by local authorities or to specific sectors, and may not apply universally across China. The date given may indicate when the directive was leaked, rather than when it was issued. CDT does its utmost to verify dates and wording, but also takes precautions to protect the source. See CDT’s collection of Directives from the Ministry of Truth since 2011.

source https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2021/07/minitrue-warn-vendors-against-foreign-media-interviews-on-henan-floods/

Friday, 23 July 2021

Minitrue: Focus on Henan Flood Recovery; Do Not Report on Celebrity Tax Case or COVID Origins Press Conference

The following censorship instructions, issued to the media by government authorities, have been leaked and distributed online. The name of the issuing body has been omitted to protect the source.

Regarding the heavy rain striking Henan and other places, shift the focus of reporting toward post-disaster recovery. Without prior permission, do not publish unauthorized images showing dead bodies, take an exaggeratedly sorrowful tone, or hype or draw connections to past events. Strictly adhere to authoritative information with regard to statistics on casualties or property damage.

Do not report on the Zheng Shuang tax case.

This morning, the State Council will hold a press conference on tracing the origins of COVID-19. Do not report. (July 23, 2021) [Chinese]

Extraordinarily heavy rainfall caused massive flooding in Henan this week. The confirmed death toll in Zhengzhou, the provincial capital, rose to 51 on Friday, with another 400,000 displaced and damage amounting to $10 billion dollars. The situation in rural areas remains unclear, but is likely to be worse. CDT compiled an overview on Thursday of English-language news and social media coverage, highlighting a further selection of posts from CDT Chinese. Natural disasters are a perennial focus of censors in China, particularly due to frequent criticism of official preparations or responses. For more on official handling of natural disasters and their aftermaths, see CDT’s interview with historian Jeremy Brown.

Actor Zheng Shuang was at the centre of two major scandals earlier this year, one involving the alleged abandonment of two children born to surrogate mothers in the United States, and the other over alleged tax evasion and contract fraud. On Monday, Zheng broke a months-long silence on Weibo, promising "to accept criticisms from all sides and consciously reflect on my mistakes," and "to make up the shortfall if there are errors caused by my negligence or unprofessionalism. I hope the tax authorities can accord me due process and not be influenced by the surrogacy incident." Such due process is not guaranteed: law professor Donald Clarke noted regarding a similar case against megastar Fan Bingbing in 2018 that "according to the Chinese government’s own story, this is an ordinary case of tax evasion by a rich person. And yet even in this ordinary case, the state could not manage to follow its own rules.” CDT published several directives related to the Fan Bingbing case, two governing reports and comments on entertainment industry "yin-yang contract" tax evasion, and a third forbidding critical commentary on subsequent tax collection changes.

Also this week, Chinese authorities rejected plans from the World Health Organization for further investigation of the COVID-19 pandemic’s origins.

Since directives are sometimes communicated orally to journalists and editors, who then leak them online, the wording published here may not be exact. Some instructions are issued by local authorities or to specific sectors, and may not apply universally across China. The date given may indicate when the directive was leaked, rather than when it was issued. CDT does its utmost to verify dates and wording, but also takes precautions to protect the source. See CDT’s collection of Directives from the Ministry of Truth since 2011.

source https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2021/07/minitrue-focus-on-henan-flood-recovery-do-not-report-on-celebrity-tax-case-or-covid-origins-press-conference/